State laws that restrict people with mental illness, including substance use problems, from gaining access to firearms differ widely across the nation, according to a review of these laws in the August American Journal of Psychiatry.

The laws differ in their definition of mental illness, type and duration of gun restriction, and reporting practices on the part of physicians caring for these patients, according to the report.

This diversity is why psychiatrists must familiarize themselves with the laws governing the state in which they practice regarding the licensure, purchase, possession, and carrying of firearms, lead author Donna Norris, M.D., told Psychiatric News.

“We as psychiatrists should be prepared to deal with these issues, whether we practice in rural or inner-city areas,” said Norris, APA's secretary-treasurer and an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

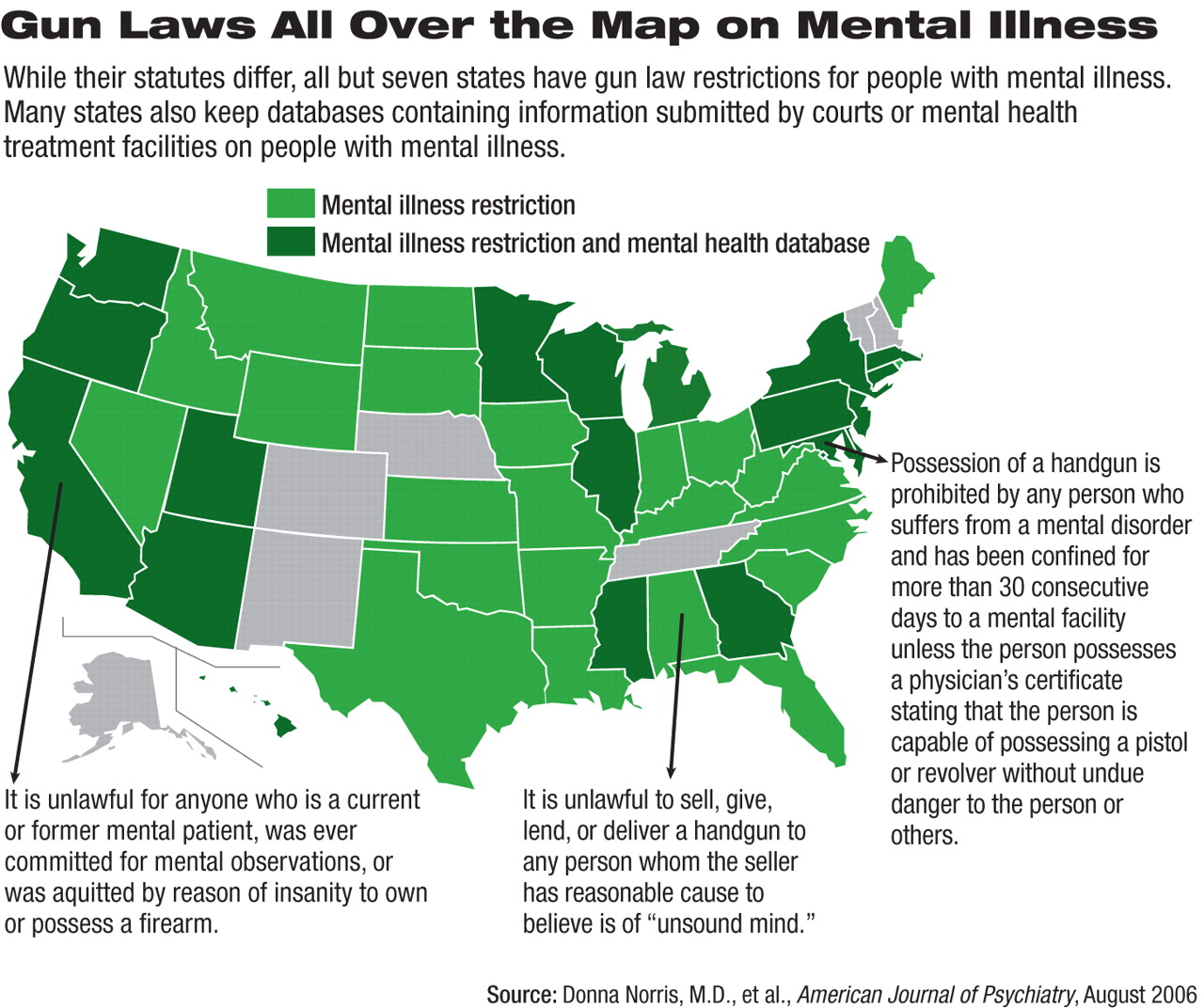

When Norris and her colleagues began to review the state laws in 2000, only 19 states had legislation restricting gun ownership for people with mental illness, she noted. But by the end of the review in 2005, 43 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico had laws prohibiting people with mental illness from obtaining firearm licensure, 36 states and Puerto Rico had similar prohibitions for those with substance use problems, and 31 states, Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico had similar prohibitions for those with alcohol problems.

Twenty states and Washington, D.C., have databases containing information submitted by courts or mental health treatment facilities on people with mental illness. In California, for instance, people who have been admitted to a psychiatric hospital and ruled a danger to themselves or others must be reported to the local law enforcement agency by an attending health care professional, according to the report.

“In most jurisdictions, law enforcement authorities have access to these mental health data and can use them to determine legal access to firearms,” the report stated.

The flurry of legislation may be related to isolated incidents of violence perpetrated by people with mental illness using guns and the firestorm of publicity often generated as a result, noted Norris.

She found that many of the variations between state laws prohibiting people with mental illness from legally obtaining or carrying firearms depended on each state's definition of restricted individuals.

According to the report, individuals who are restricted from gun ownership include those who currently receive outpatient psychiatric treatment, those who have been civilly committed to treatment, and those who have been declared not guilty by reason of insanity. Some are prohibited because they have a history of alcohol or substance abuse.

The laws vary in their range of restrictiveness. In Pennsylvania, for example, prohibitions extend to those who have been “adjucated as an incompetent,” been committed to receive psychiatric care on an inpatient unit, or been convicted of driving under the influence of alcohol or a controlled substance on three or more occasions within a five-year period.

Texas law prohibits the ownership and carrying of guns by those with certain psychiatric diagnoses, including schizophrenia, delusional disorder, bipolar disorder, chronic dementia, dissociative identity disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. In addition, gun restrictions are in place for five years following an involuntary psychiatric hospitalization, inpatient or residential treatment for substance abuse, diagnosis of alcohol or drug dependence, or diagnosis of mental illness by a licensed physician.

Patients in certain states who wish to apply for permission to purchase, possess, or transfer a handgun must present with their application a written affidavit from their psychiatrist or physician. In Massachusetts, for instance, this affidavit must state that the physician is aware of the patient's mental illness and the patient is not disabled by the illness“ in a manner that should prevent the applicant from possessing a firearm, rifle, or shotgun....” The statute goes on to specify that if the applicant has been treated for drug or alcohol addiction, he or she must have been “cured” of the addiction by a licensed physician to own a firearm.

“There is some risk attached to this responsibility,” Norris noted. “Can you really testify that the patient is `cured,' and what does this really mean?” she asked.

In Rhode Island, a restricted person must be pronounced “cured” by a physician for at least five years to be considered a “mentally stable person and a proper person to possess firearms.” For handgun licensure in Oklahoma, individuals who have been treated for mental illness must have their physician testify that they have been mentally stable for at least 10 years.

Psychiatrists may also have other duties. In California and Colorado, psychiatrists treating inpatients must report gun possession to local law enforcement or judicial authorities.

In states with no specified restrictions, federal law takes effect. The Federal Gun Control Act “prohibits the transfer of any firearm to any person who... is an unlawful user of or addicted to any controlled substance [or] has been adjucated as a mental defective or committed to a mental institution.”

In an editorial appearing in that same issue of American Journal of Psychiatry, Paul Appelbaum, M.D., chair of APA's Council on Psychiatry and Law, noted that the variability in statutes across the United States poses“ a dilemma for advocates for persons with mental disorders, including psychiatrists and their national organizations.... But given that only a tiny fraction of violence, including gun violence, is perpetrated by persons with mental disorders, efforts that center disproportionately on restricting their access reflect a deeply irrational public policy.”

Appelbaum also expressed concern about the creation of databases that accumulate information about people with mental illness and can be assessed by states before the sale of a firearm. Such access may threaten the confidentiality of psychiatric treatment.

“Whether singling out persons with mental disorders, including substance abuse problems, for restrictions with regard to gun purchases is an effective means of protecting the public cries out for careful assessment,” he said.