The attack on the World Trade Center the morning of September 11, 2001, was the deadliest terrorist act ever committed on U.S. soil. Arriving at a final tally of the dead— about 2,800—stretched out agonizingly for months, and confirming victims' identities seemed like a never-ending puzzle. But if it is possible that something good can come out of something almost too horrible to imagine, it is this: officials of the New york State Office of Mental Health (OMH) knew that many people would be severely traumatized by the attack and realized the importance of providing mental health assistance quickly. They also realized they had an unprecedented opportunity to learn lessons that could inform future disaster-response plans.

“Disasters present terrible opportunities to learn about how to get people needed mental health services,” said Susan Essock, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and director of the Division of Health Services Research at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New york City.

Essock collaborated with OMH staff on the development and implementation of Project Liberty, New York state's crisis counseling program.

Project Liberty, funded by grants totaling $155 million from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), quickly became the largest federal government-funded disaster mental health program in history. New York's OMH took the lead in implementing the program in collaboration with approximately 200 local agencies.

The Project Liberty program was implemented to “provide free and anonymous community-based mental health services to help individuals recover from their psychological distress and regain their predisaster level of functioning,” according to project literature. The services offered were based on the assumption that most people's stress reactions, although significantly disturbing to them personally, constituted normal responses to a traumatic event, and that the reactions would dissipate over the short term.

As such, the range of interventions offered under Project Liberty was aimed at helping people identify their trauma responses, understand that those responses were normal, and reconnect with previously existing social support networks.

“One of the fundamental things we learned,” said Chip Felton, M.S.W., an OMH senior deputy commissioner and chief information officer for OMH's Center for Information Technology and Evaluation Research, “was that it proved possible to set up and run a very large crisis counseling and emergency mental health program and that, in fact, it seemed to be something that really resonated with a large number of people.”

The September issue of the APA journal Psychiatric Services presents a special section containing a series of 15 reports detailing data on numerous aspects of the project, from demographic characteristics of those who used Project Liberty services to data on outcomes of interventions and quality assurance/quality improvement metrics.

According to those reports, between the time of Project Liberty's launch in the weeks following September 11 and the point when its services ceased on December 31, 2003, Project Liberty provided face-to-face counseling and educational and outreach sesrvices to an estimated 1.2 million individuals in the New York City metropolitan area. About 465,000 individuals received nearly 690,000 individual crisis counseling sessions. Almost 550,000 individuals were provided public education on trauma.

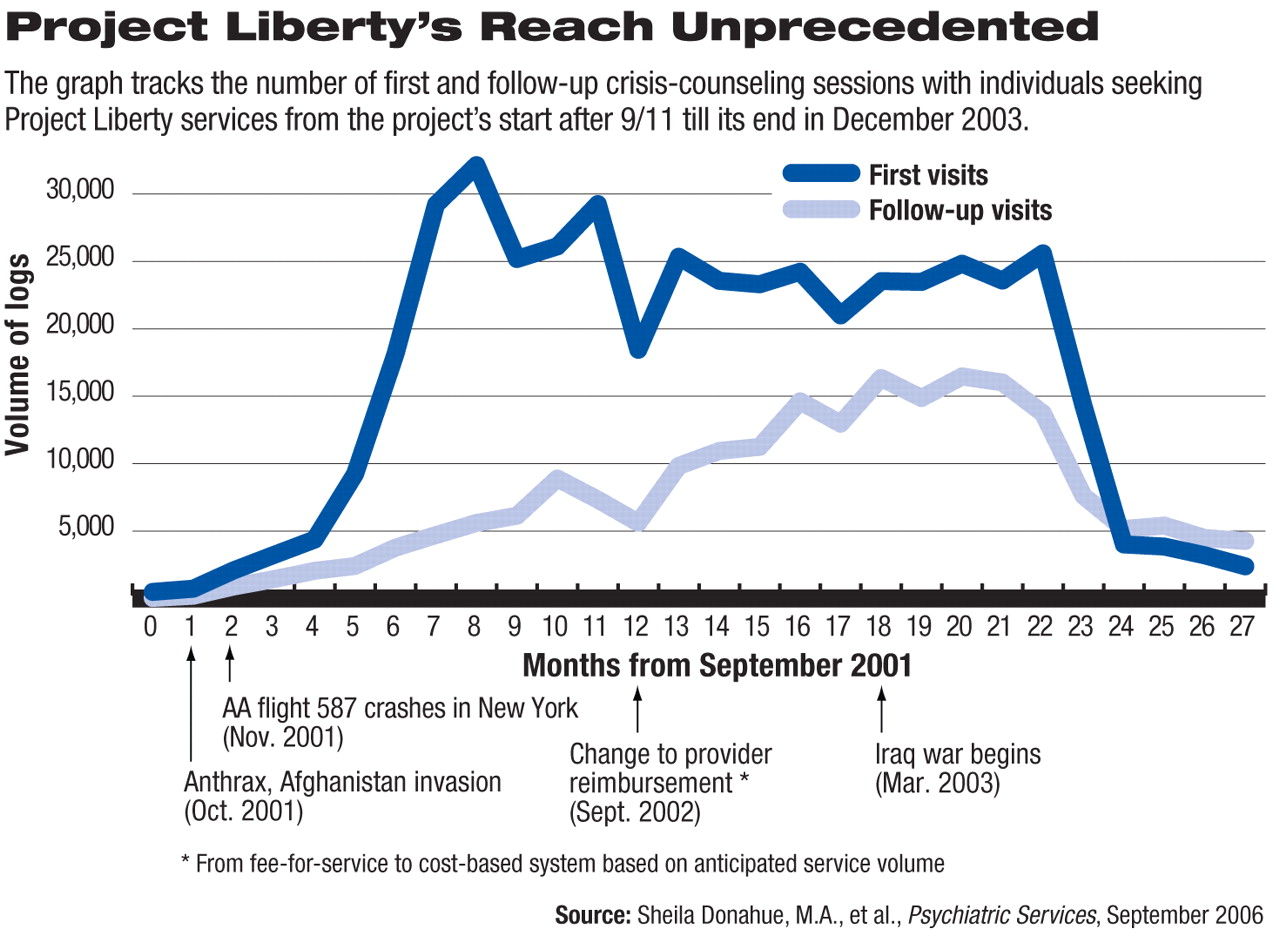

Just under 700 counseling and educational sessions were provided in September 2001, and the number of sessions each month almost doubled through April 2002. The project reached its peak during May 2002, during which 41,000 sessions were provided to individuals by Project Liberty counselors. Service utilization remained near that level through August 2003, when the project began its phase-down in preparation for its cessation at the end of 2003 (see

chart).

For those with mild to moderate symptoms, “crisis counseling” under Project Liberty ranged from informal sessions with counselors that included simply discussing and validating a patient's feelings to more structured sessions focusing on recovery skills, coping mechanisms, and reliance on social-support networks.

By early summer 2002, it became apparent to Project Liberty staff that there was a group of individuals who were repeatedly showing up, looking for help. Felton and his colleagues decided to seek permission from federal regulators to expand the scope of Project Liberty to offer more intensive crisis counseling. Regulators approved offering enhanced services, which included a cognitive-behavioral intervention that was specifically developed to treat posttraumatic stress (see article on facing

page).

In total, 753,015 counseling and educational sessions were provided between September 2001 and December 2003.

Disaster Response Matures, Evolves

“We found that as part of putting together this large, overall infrastructure supporting a very-large-scale public health initiative, it was in fact feasible to collect anonymous but key pivotal data from thousands of people who served as crisis counselors,” Felton told Psychiatric News. “Those data were important to us in many different ways as we tried to manage the ongoing program, and hopefully in the longer term, [we will all be] more prepared for disaster response in the future.”

In a “Taking Issue” column in the September Psychiatric Services, Betty Pfefferbaum, M.D., J.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, and Bradley Stein, M.D., Ph.D., a visiting associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, wrote,“ The reports from Project Liberty in this issue of Psychiatric Services attest to the wealth of experience and the explosion of knowledge and understanding gained in work associated with the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

“Disaster mental health care has evolved, and its growth is reflected in the ability to respond to succeeding disasters of increased dimensions in the context of more complex and devastated environments. Research is also advancing.”

“The reports from Project Liberty show us how far we've come,” Stein told Psychiatric News. The field of disaster response has significantly improved compared with where the field of disaster response was 10 years ago, he said.

“In particular, the federal response has matured,” Stein explained. “When you get federal regulators, researchers, state officials, and counseling providers together, it is indeed possible to build quality indicators into a disaster response program.”

Tracking Quality in Disaster Response

Project Liberty was the first FEMA-funded disaster response program to include quality assurance/quality improvement measures.

Felton, Essock, and their colleagues requested that the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) specifically allocate funds for program evaluation.

“The data analysis was as close to real time as we could get with a paper-based reporting system,” Felton explained. Every two weeks, Project Liberty leaders got a new feed of data from the service encounters.

“We were able to use that information, not just centrally as the state mental health authority administering the program,” added Sheila Donahue, M.A., who served as the director of Project Liberty, “but also to provide the data to the counties and at the individual provider level on an ongoing basis.”

The federal investment in the evaluation structure needed to collect this information and use it in proactive ways was absolutely vital and led to a significant pay off, said Donahue, who is currently the director of data analysis and performance measures at the New York OMH.

“Of course, we were pleased with how the quality assurance measures in Project Liberty worked,” Felton noted. “But one of the things that is not mentioned in any of the Psychiatric Services articles is that today, if you look at SAMHSA's Center for Mental Health Services toolkit for crisis counseling programs, you will see that some of the Project Liberty assessment tools are now included as recommended tools.”

The Psychiatric Services special section on Project Liberty is posted at<www.ps.psychiatryonline.org>.▪