Approximately three-quarters of subjects with psychiatric illness who report committing serious violent crimes also report experiencing some form of“ leveraged treatment.”

A number of demographic and clinical factors are associated with the experience of leveraged treatment. These include younger age, male gender, poorer clinical functioning, more years in treatment, more frequent hospitalizations, higher frequency of outpatient visits, and negative attitudes toward medication adherence.

Those findings suggest that a combination of concerns about safety and treatment nonadherence may influence decisions by clinicians and judges to apply legal leverage, wrote Jeffrey Swanson, Ph.D., and colleagues in the August American Journal of Psychiatry.

Leveraged treatment refers to any of a wide range of strategies to induce patients to comply with treatment. These may include mandated community treatment whereby incarceration or placement in subsidized housing can be made contingent on compliance, appointment of a money manager to make a patient's access to funds contingent on treatment adherence, and lenient sentencing by judges on the condition that a person participate in treatment.

“The findings suggests that a history of violence per se is not considered a sufficient rationale for applying legal leverage to psychiatric outpatients, assuming the patient is willing to accept treatment voluntarily,” Swanson told Psychiatric News. “They also suggest that a patient's unwillingness to take medication is not, in and of itself, sufficient to warrant legally mandating treatment in the community, as long as the patient poses no risk of violence. However, if a potentially violent patient is unwilling to take medication, psychiatrists are more likely to resort to legal leverage, partly out of concern for their own professional liability in an adverse event. Similarly in the criminal-justice system, a judge may order a defendant with mental illness to participate in treatment as a condition of living in the community, especially if the person isn't likely to accept treatment voluntarily and may become violent without it.”

Swanson is an associate professor of psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine.

In the study, approximately 200 out-patients were recruited at publicly funded mental health treatment programs in each of five cities: Chicago, Durham, N.C., San Francisco, Tampa, Fla., and Worcester, Mass. A single structured interview lasting about 90 minutes was administered in person by a trained lay interviewer. Participants were paid $25 for the interview.

The researchers assessed whether respondents had experienced no leverage, social leverage only (such as leverage involving money or housing), legal leverage only (outpatient commitment or leverage applied through the criminal justice system), or both types of leverage.

They used the MacArthur Community Violence Interview to assess study participants for violent and aggressive behavior during the previous six months.

Across study sites, 18 percent to 21 percent of participants reported having committed violent acts in the prior six months. Those who reported having used or made threats with a lethal weapon, committed sexual assault, or caused injury ranged from 3 percent to 9 percent.

About three-quarters of subjects who reported such serious violence also reported having experienced some form of leveraged treatment, compared with about one-half of subjects who did not report serious violence.

Across the five sites, the proportion of respondents reporting social welfare leverage alone ranged from 15.7 percent to 26.3 percent of respondents. Legal leverage alone was reported by 11.2 percent to 17.0 percent.

The proportion of respondents who experienced both types ranged from 12.8 percent to 18.5 percent.

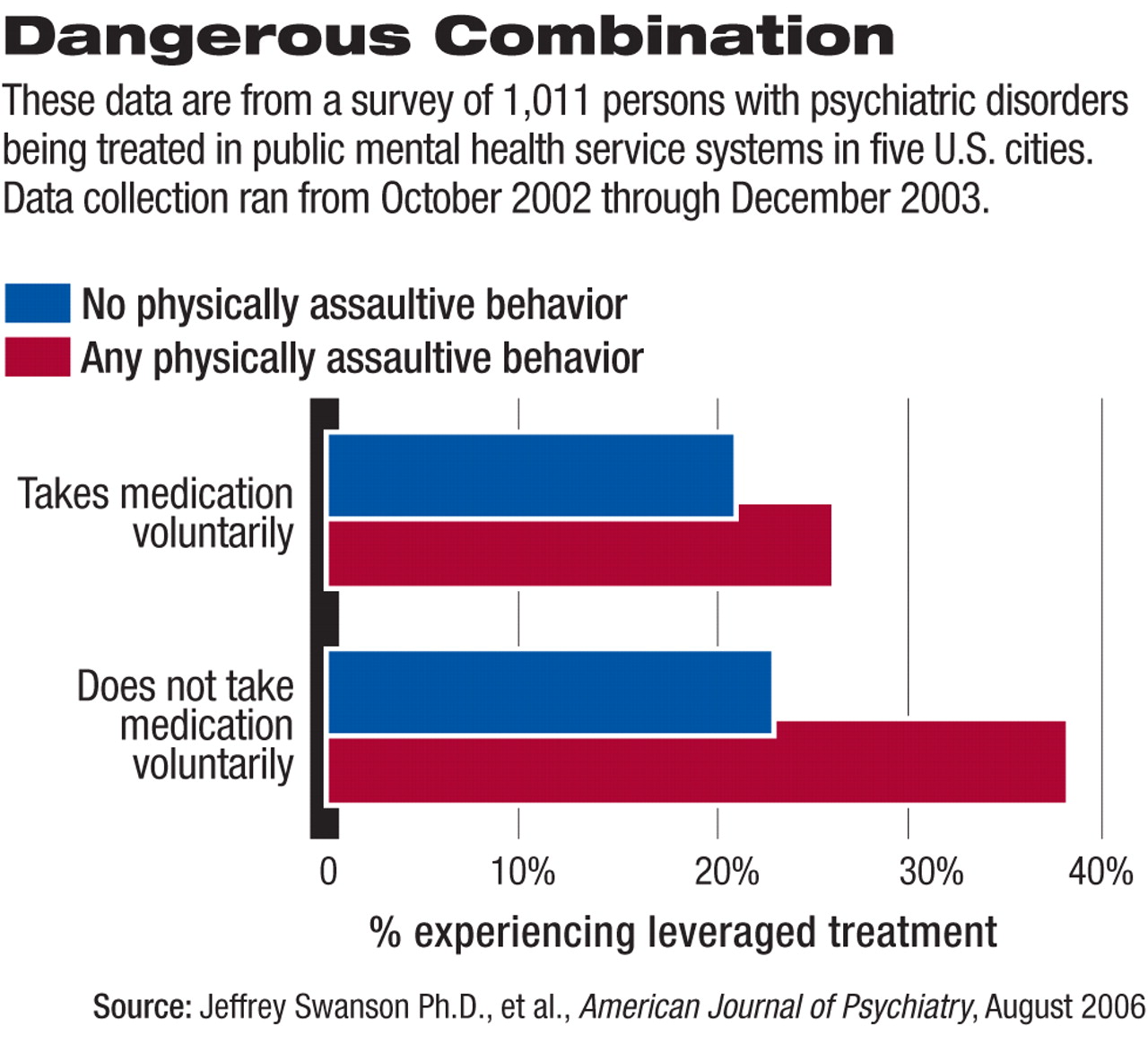

People who reported any physically assaultive behavior and also did not take medication voluntarily were more than twice as likely to have experienced legal leverage (see

chart).

“Treating clinicians should understand that the use of leveraged community treatment is now a common part of the landscape of mental health services for adults in the United States,” Swanson told Psychiatric News. “Violence risk is sometimes cited as the reason for this, but clearly leverage is not all about preventing violence. In fact, the use of leverage is far more common than violence itself is among public psychiatric outpatients.”

Is leverage being applied appropriately? “We don't know enough about that,” Swanson said. “It's likely that the use of leverage to ensure adherence does prevent violence to some extent. That's probably why about three-quarters of patients with serious violent behavior have received some type of legally leveraged mental health treatment. But the main goal in the application of leverage should be to improve the effectiveness of treatment in the community—that is, to help meet the complex needs of people with severe mental illness and not to focus only on reducing serious violence, which is actually quite a rare phenomenon among these patients. Otherwise it's going to be a misapplied policy in most cases.”

Paul Appelbaum, M.D., chair of APA's Council on Psychiatry and Law, said the study brings to light for the first time the frequency with which various forms of leverage are used.

Appelbaum was in charge of the study site at Worcester, Mass., and was involved in planning the study and analyzing the data.

“Until the study from which these data were drawn, we had no idea of the frequency of these forms of leverage,” he said. “So a major effect of the underlying study, as well as this analysis, has been to surface these behaviors and enable discussion about their legitimacy to begin.

“It can be concluded that people who are subject to leverage are at higher risk for reporting violence, but it's not clear that violence was the reason that they were subjected to leverage,” Appelbaum told Psychiatric News. “As an alternative hypothesis, it could be that violent patients are also more symptomatic, and it was their higher levels of symptomatology that led to leverage use.”

In an editorial accompanying the article, appelbaum noted that “it remains an open question” whether leveraged treatment is effective in reducing violence.

“Among the variables likely to determine effectiveness in a given population are the extent to which violence is linked to psychiatric symptoms, the efficacy of treatment in reducing those symptoms, the availability of treatment, the degree of compliance with treatment (which may relate to how aggressively the mandates are enforced), and the degree to which positive effects carry over after the termination of the mandate,” he wrote.

In his comments to Psychiatric News, Appelbaum drew a distinction between mandated out-patient treatment and the forms of leverage experienced by most of the patients in the study.

“Only a minority of subjects in this study were exposed to outpatient commitment,” he said. “The other forms of leverage that were used tend to be much less visible, though they may—ironically—be more coercive. Most outpatient commitment statutes lack real enforcement provisions. But treatment requirements imposed by the criminal justice system are ignored only at the risk of being incarcerated, and leverage using housing or control of money has real consequences as well.”