The power of a placebo is nothing new to psychiatrists, but documenting a placebo's punch inside the brain is more novel.

More specifically, changes in a depressed person's brain before treatment can predict, to a sizable extent, whether the individual will respond to treatment, a new study has found.

The placebo lead-in phase is common to many efficacy studies of antidepressant medications. Typically, subjects receive a placebo from three to 14 days before being randomly assigned to a placebo or medication. This initial drug-free interval allows the effects of the study drug to be evaluated without being compromised by pre-existing medications. Aimee Hunter, Ph.D., a research psychologist at the UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, and her coworkers decided to capitalize on the placebo lead-in phase of an antidepressant trial to learn more about a placebo's impact on the brain and the possible influence of this impact on treatment outcome.

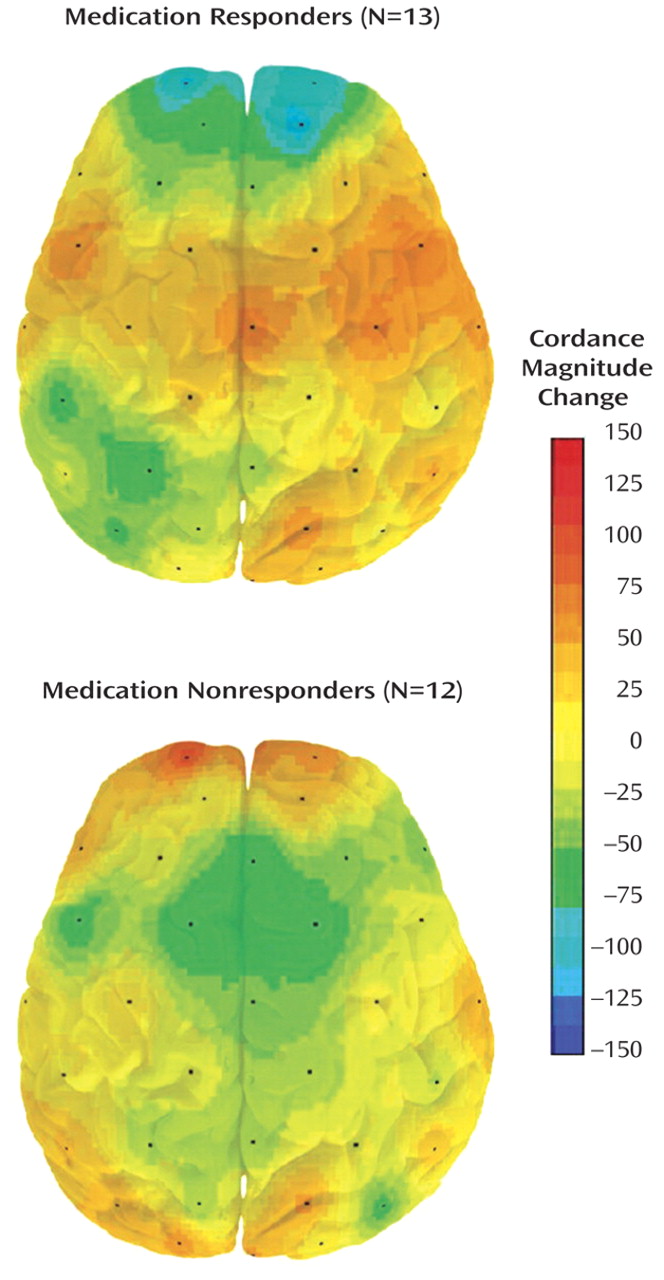

Fifty-one subjects diagnosed with major depression and participating in a double-blind, placebo-controlled antidepressant trial with a placebo lead-in phase were included in this experiment. Brain electrical activity was measured both before and after the one-week placebo lead-in phase with a technique developed at UCLA called quantitative EEG cordance. The technique involves placing electrodes on a subject's scalp to pick up electrical signals, which are then fed into a computer. The computer then measures the electrical signals coming from the subject's brain and processes them into colorful patterns.

The subjects' level of depression was then assessed using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D). Subjects were randomized to receive either an antidepressant or a placebo for eight weeks; at the end of that time, depression levels were measured once more with the HAM-D. Finally, the scientists looked to see whether there were changes in subjects' brain electrical activity during the placebo lead-in period, and if so, whether the changes could be linked with their clinical outcome.

The answer was yes on both counts, and not just for those subjects getting an antidepressant, but also for those getting a placebo, the researchers reported in the August American Journal of Psychiatry.

In the subjects given an antidepressant, decreases in prefrontal cortex electrical activity during the placebo lead-in period were significantly associated with lower depression scores at the end of the eight-week treatment period. Nineteen percent of the variance in depression scores, in fact, could be explained by brain electrical activity that occurred during the lead-in period.

In the case of the subjects given a placebo, increases in right temporal lobe electrical activity during the placebo lead-in period were significantly linked with lower depression scores at the end of the eight-week treatment period. Twenty percent of the variance in depression scores could be explained by brain electrical activity that occurred during the lead-in period.

“We were surprised that 19 percent of the variance in final HAM-D scores was predicted by brain changes occurring before start of drug,” Hunter told Psychiatric News. “That's a fairly large proportion, especially considering that the placebo lead-in period was only one week long compared to eight weeks of treatment with medication. We also were surprised to find different brain changes [that is, increases in right temporal electrical activity] during placebo lead-in that were associated with eventual response in the placebo group.”

However, when asked why decreased prefrontal activity predicted less depression in subjects getting an antidepressant, and why increased right temporal activity predicted less depression in subjects getting a placebo, Hunter said that she and her team do not know. Nor do they have an answer for why brain electrical activity changes at all during a placebo lead-in period. But as Ian Cook, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at UCLa and senior author of the study, told Psychiatric News, “We are now conducting a study, with NIH support, to examine some candidate factors—for example, prior experience with treatment, beliefs about treatment, and empathic alliance with care providers.”

Meanwhile, he said, a practical implication of their study results for clinical psychiatrists “is that the `treatment' to which our patients respond extends beyond the molecules in our pills and capsules, and that many other features of the overall treatment system count.”

The study was funded by the National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, the National Institute of Mental Health, Lilly Research Laboratories, and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals.