Atricyclic antidepressant and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) provided comparable symptom reduction among women with postpartum major depression, according to a randomized comparative study.

The eight-week, double-blind trial of the tricyclic nortriptyline and the SSRI sertraline included a 16-week continuation phase. Published in the August Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, the study found that groups of participants divided between the two drugs had the same response rates at four, eight, and 24 weeks.

Findings from the 109 patients enrolled in the study ran counter to the expectations of the researchers, who anticipated that the SSRI would be more effective, due to findings pointing to such a conclusion from previous pilot studies.

“These two drugs from different antidepressant classes were equally effective for response and remission for postpartum depression,” said Katherine Wisner, M.D, the study's lead author. “So it's reasonable to use drugs from either of these two classes.”

Wisner is a professor of psychiatry, obstetrics, and gynecology and director of Women's Behavioral Healthcare, at Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic at the University of Pittsburgh.

The eligibility and outcomes were measured with a 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D), and other measures looked for side effects.

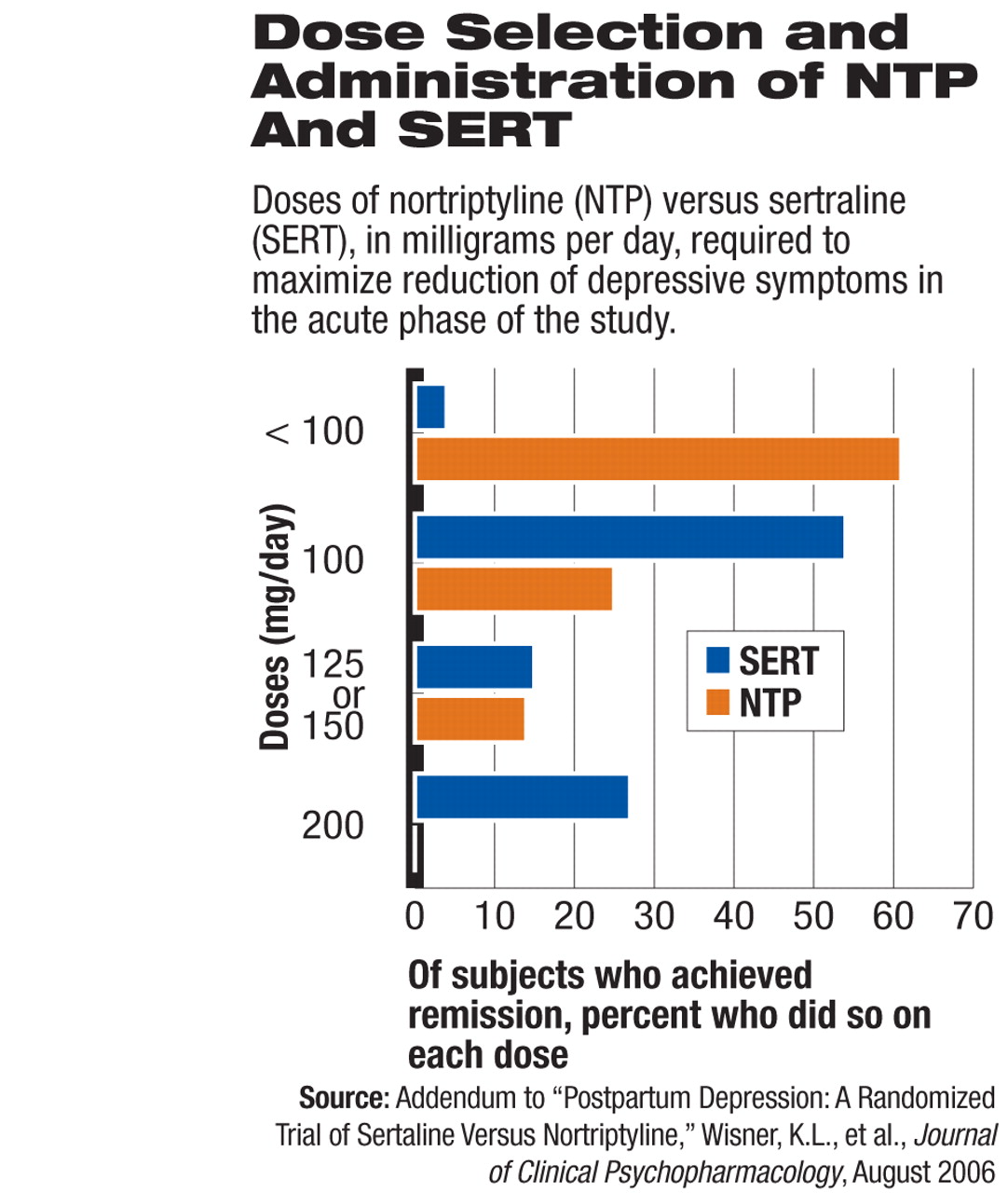

At four weeks, 25 of the 55 women (46 percent) taking sertraline responded to the medication—defined as a 50 percent reduction in their Ham-D score—and 30 patients of 54 patients (56 percent) taking nortriptyline responded.

An additional 15 patients (27 percent went into remission on sertraline—defined as a Ham-D score of less than 7—while 16 women (30 percent) did so on nortriptyline.

By the eighth week, 94 percent of study participants had Clinical Global Improvement scores that indicated significant improvement, and there were no significant differences between patients on the two groups of drugs.

The study authors observed no adverse effects in babies of breastfeeding mothers, and tests showed that serum levels in those infants were near or below the “level of quantifiability” for both drugs.

The findings could have a broad impact because previous research has identified depression in nearly 15 percent of women within the first three months after giving birth.

Ruta Nonacs, M.D., Ph.D., who provides extensive postpartum depression care, said the findings fill a void in research on the efficacy of tricyclic antidepressants in postpartum patients and make her more inclined to prescribe the drugs.

“This makes me more comfortable with using tricyclics, which do look like they work quite well,” Nonacs said.

A more subtle finding that surprised Nonacs, associate director of the Center for Women's Health at Massachusetts General Hospital and an instructor in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, is that the study seemed to refute the general belief among psychiatrists and other physicians that SSRIs are better at treating intrusive obsessive symptoms in women.

“But both antidepressants worked equally well in taking care of those obsessive symptoms,” Nonacs said. “So it seems like it's not necessarily an OCD symptom that you are treating but the overall level of anxiety, and those OCD-type symptoms resolved.”

Nonacs, who said that half of her patients are being treated for postpartum depression, noted that another important finding of the study is that many women, regardless of which drug they were taking, began responding by two weeks into the trial.

Little was previously known about the treatment response rates for medication among women with postpartum depression, so the researchers hypothesized that they would be similar to the drugs' efficacy in treating major depression. The findings support that assumption.

APA Vice President Nada Stotland, M.D., M.P.H., agreed that the findings appeared to expand the medical options of physicians treating depression, especially for those concerned that nursing mothers' exposure to SSRIs may be associated with impaired neurocognitive development in their children.

The study's finding are unique in many areas because it is still rare for researchers to conduct work with pregnant and breastfeeding women because of concerns for the health of the child, said Stotland, an expert on women's mental health and a professor of psychiatry and obstetrics/gynecology at Rush Medical College in Chicago. The safety and efficacy findings are important in this class of patients because they may encourage women to continue their drug therapy and avoid the high depression relapse rates previous research has identified among women who discontinue treatment while breastfeeding. Other research has found that delaying treatment is the most significant factor in the duration of depression.

“Ultimately, what is good for mommy is good for baby,” Stotland said. “A depressed mother doesn't eat well, doesn't sleep well, and isn't going to be able to take good care of the baby.”

The study's safety findings, Stotland said, also support the understanding that psychiatrists should continue medical therapy in the postpartum period for women already on antidepressants. However, women who are newly diagnosed with postpartum depression should always begin treatment with psychotherapy, except in cases of severe depression.

The study was funded by NIMH. Pfizer provided the sertraline.

“Postpartum Depression: A Randomized Trial of Sertraline Versus Nortriptyline” is posted at<www.psychopharmacology.com. Click on the “Search” tab, then enter “Wisner” as author, and “sertraline” in the Title field. >.▪