Researchers in Washington state have found that the risk of suicide and serious suicide attempts is highest in the 30 days before patients begin taking an antidepressant medication, rather than the month following initiation of drug therapy. With continued antidepressant use, the researchers said, risk of suicide death remains fairly constant through the first six months of treatment, while risk of a suicide attempt serious enough to result in hospitalization steadily decreases.

The new report involved an in-depth review of computerized health plan records at Seattle-based Group Health Cooperative (GHC). Between January 1, 1992, and June 30, 2003, researchers led by Gregory Simon, M.D., M.P.H., identified 65,103 GHC patients who received 82,285 prescriptions for new antidepressant treatment (many patients were prescribed trials of more than one antidepressant). Within that population, during the six months following initiation of new antidepressant treatment, 31 suicide deaths occurred, and patients were hospitalized for a serious suicide attempt 76 times.

The report, funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, appears in the January American Journal of Psychiatry.

Suicide and serious suicide attempts are “tragic but fortunately rare events,” said Simon, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington and a staff physician and researcher at GHC's Center for Health Studies.

“We don't find any evidence to support the widely held belief that suicide risk increases when people start taking antidepressant medications,” Simon told Psychiatric News. “What we did find was that suicide risk actually decreases when people start taking antidepressants.”

Simon added that the results “do not mean that there may not be individuals who somehow have adverse reactions to these medications, but certainly on average, risk goes down [for patients on medication].”

Simon and his colleagues used GHC computerized pharmacy records and outpatient visit and hospital discharge data for all GHC health plan members during the study period. Mortality records were created for each study year by linking GHC membership rolls with state and national death-certificate data. Mortality data were included for every GHC member during the 10.5-year period, regardless of whether the member remained covered by GHC at the time of death.

All episodes of antidepressant treatment (the “index prescription”) were identified, which represented a new outpatient prescription for an antidepressant medication to any patient who had no record of any antidepressant prescription filled in the previous six months. These patients were diagnosed with unipolar major depressive disorder, dysthymia, or depressive disorder not otherwise specified during the 30 days prior to or following the prescription of the antidepressant.

Medication Clearly Reduces Risk

Patients meeting those criteria were predominantly female (69.5 percent) and ranged in age from 5 to 105. Of the 82,285 episodes of antidepressant treatment, 5,107 (6.2 percent) were in patients aged 17 or younger.

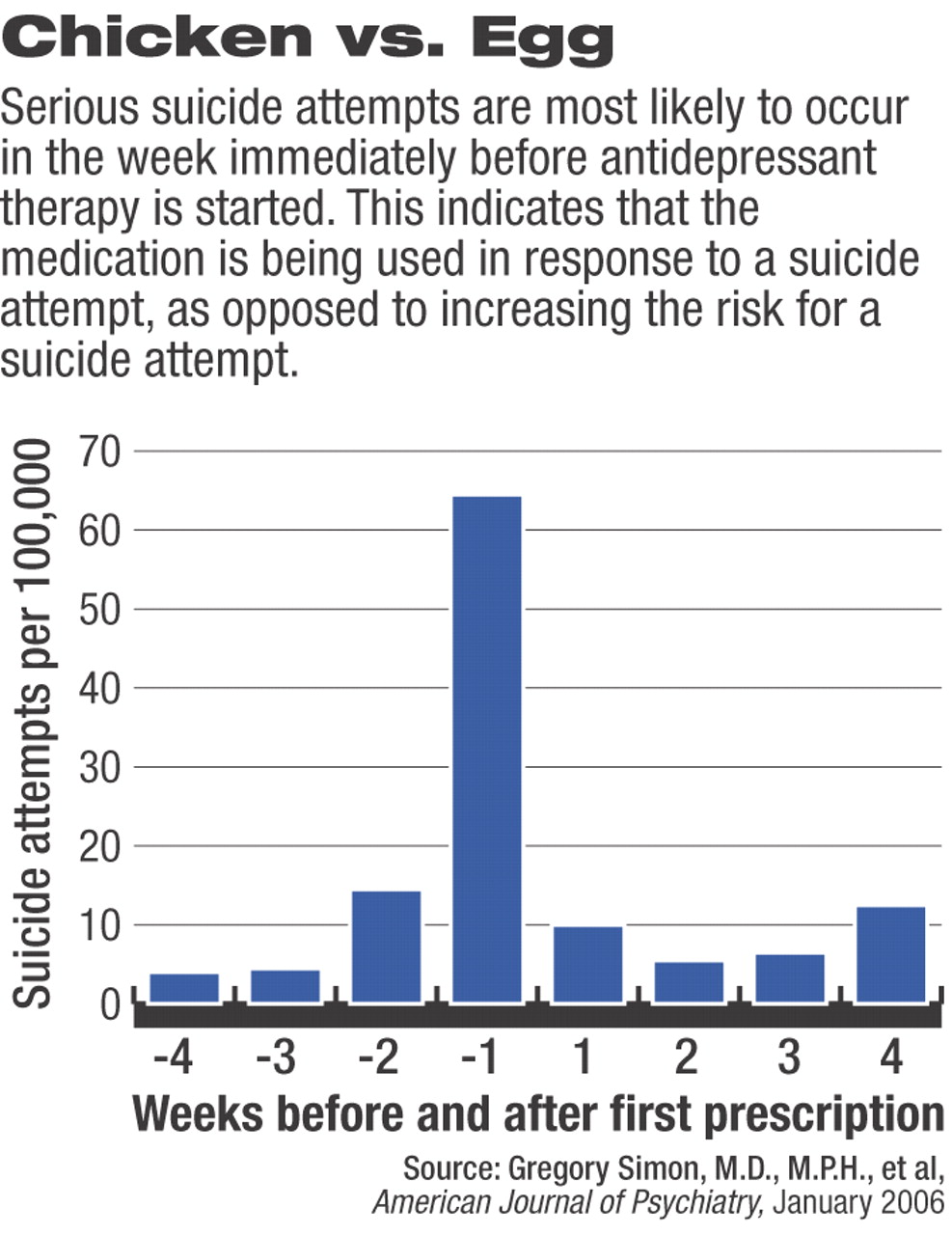

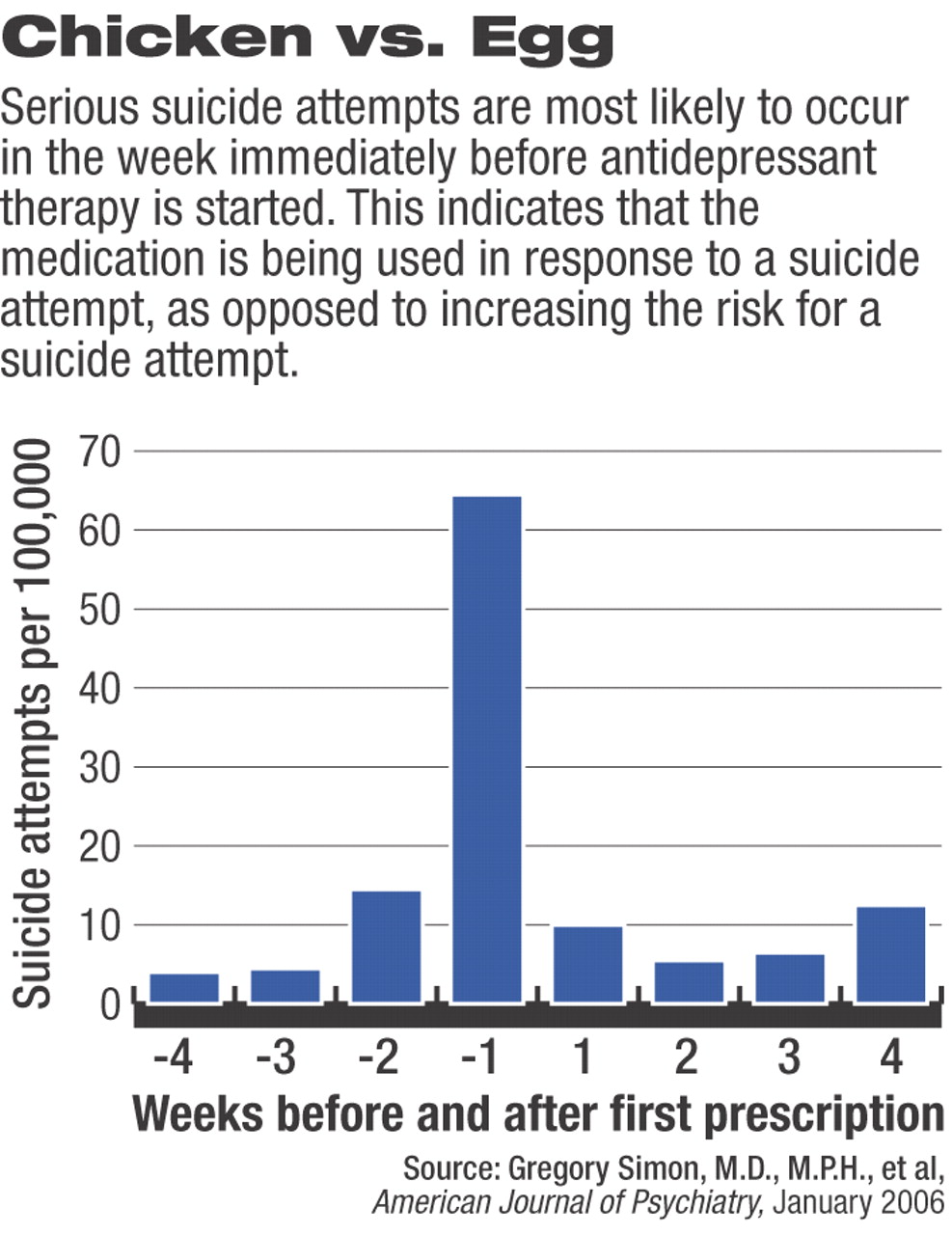

In addition to the 31 suicide deaths (a rate of 40 per 100,000 treatment episodes) and 76 serious attempts (93 per 100,000) identified in the six months following the index prescription, the researchers identified 73 suicide attempts (93 per 100,000) that resulted in hospitalization in the three months prior to an index prescription. The majority of those attempts occurred in the seven days preceding the index prescription, indicating that some patients were put on medication specifically in response to the attempt, Simon said (see

chart on page 18).

Black-Box Warnings

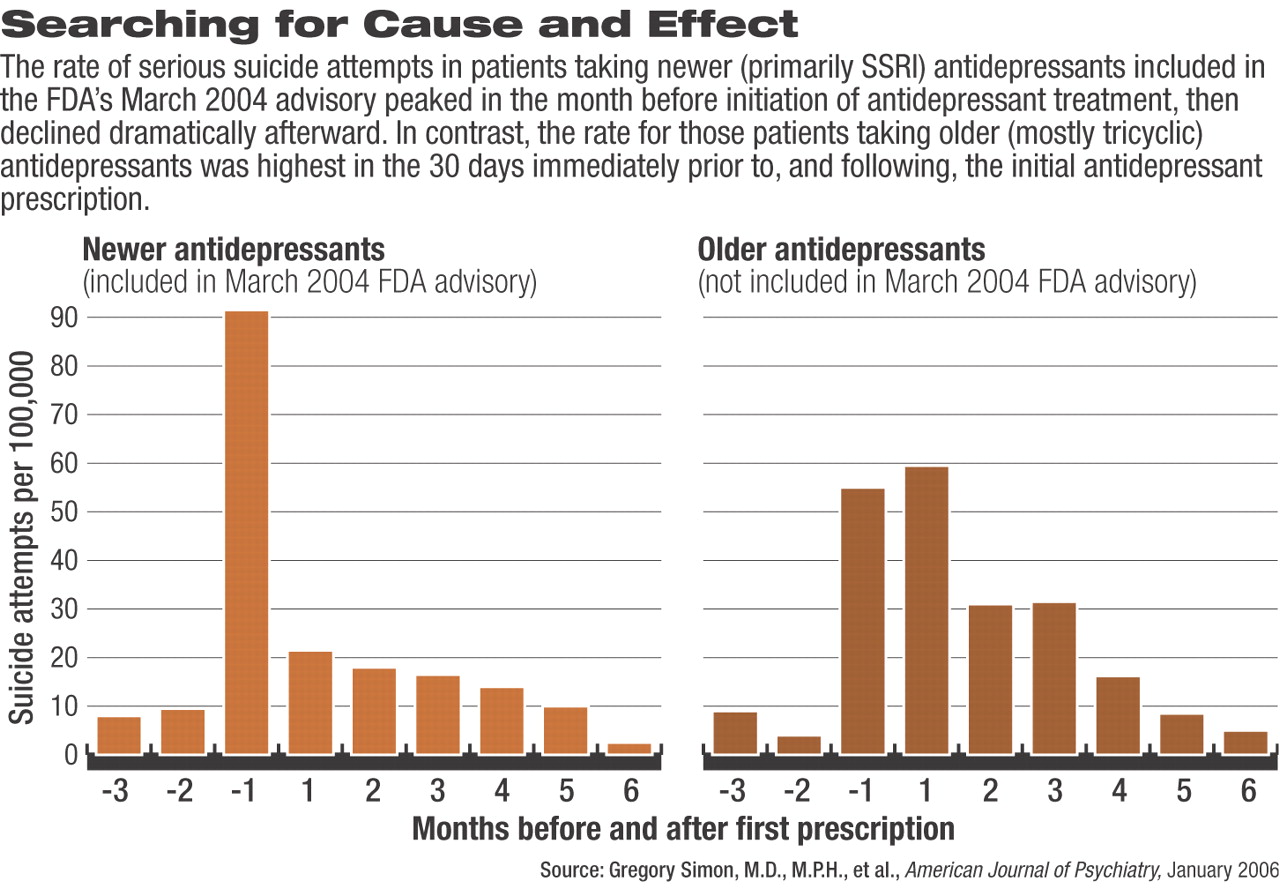

Early warnings of a potential association between antidepressant medications and increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors came in a March 2004 Public Health Advisory issued by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). That advisory included only newer antidepressants, primarily the SSRIs and SNRIs. The black-box warnings ordered by the FDA in October 2005 were expanded to include all antidepressants marketed in the United States.

Simon and his colleagues separated the 82,285 episodes of antidepressant prescriptions into older versus newer prescriptions to determine if the number of suicide deaths or serious suicide attempts differed between the different antidepressant classes.

“We found no evidence of any higher risk, or a specific risk, associated with use of newer antidepressants,” said Simon. “If anything, our data say there should be more concern associated with the older drugs.”

For patients taking newer antidepressants, risk of a serious suicide attempt was still highest in the month before the index prescription. For those patients taking older medications, risk was not statistically significantly different in the month before compared with the month after index prescription. Once on medication, both groups' risk declined significantly as medication was continued out to six months.

The researchers had received previous NIMH grants to look at specific outcomes measures pertaining to antidepressant medications. However, Simon said, they had not looked at how risk of suicide or serious suicide attempt differed before initiation of medication therapy compared with risk after medication was begun.

“When this controversy arose,” Simon said, “we already had a large dataset readily available.” However, he continued, an observational study such as this one has inherent limits and cannot clearly establish or refute a causal relationship between antidepressants and suicide risk.

“In the ideal world, what we'd like to do is conduct a true experiment—to do a large, randomized, controlled trial,” Simon explained. “But the difficulty is, if you are looking for something that is inherently fairly rare, you would have to have over 300,000 patients to have the study statistically sufficiently powered to detect a difference.”

An added difficulty, he said, occurs when trying to separate out the risk of suicide death for adults versus children and adolescents. In the data analyzed by Simon and his colleagues, “adolescents constituted a small portion” and accounted for three suicide deaths and 17 serious attempts. Risk of serious suicide attempt was four times as high in adolescents as in adults, but the pattern over time was similar in the two groups.

Further research is “clearly needed,” the researchers concluded. Until then, “closer monitoring of antidepressant treatment is needed, but warnings regarding suicide precipitated by antidepressants may do more to discourage effective treatment than to improve the quality of follow-up care.”

Am J Psychiatry 2005 163 41