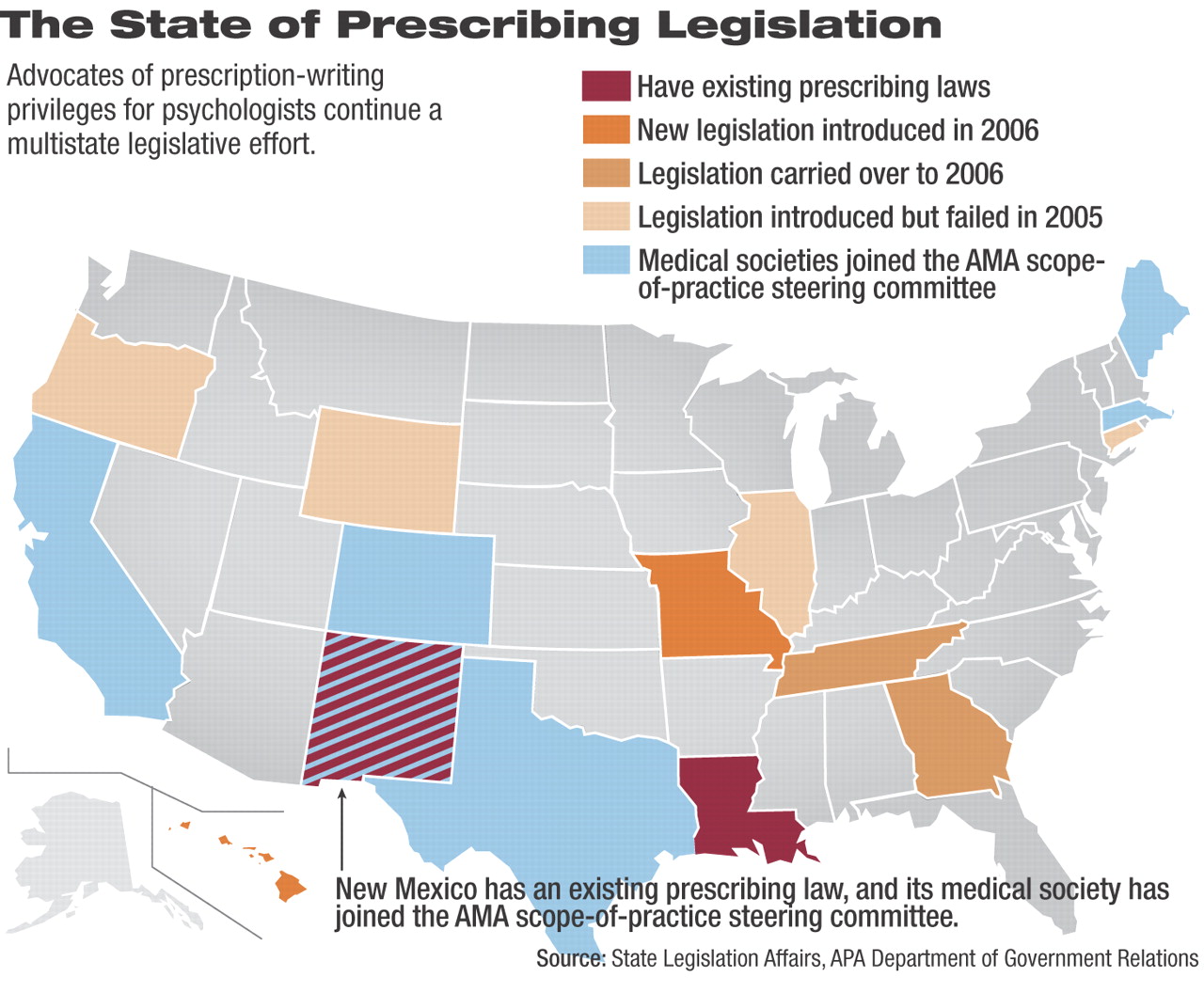

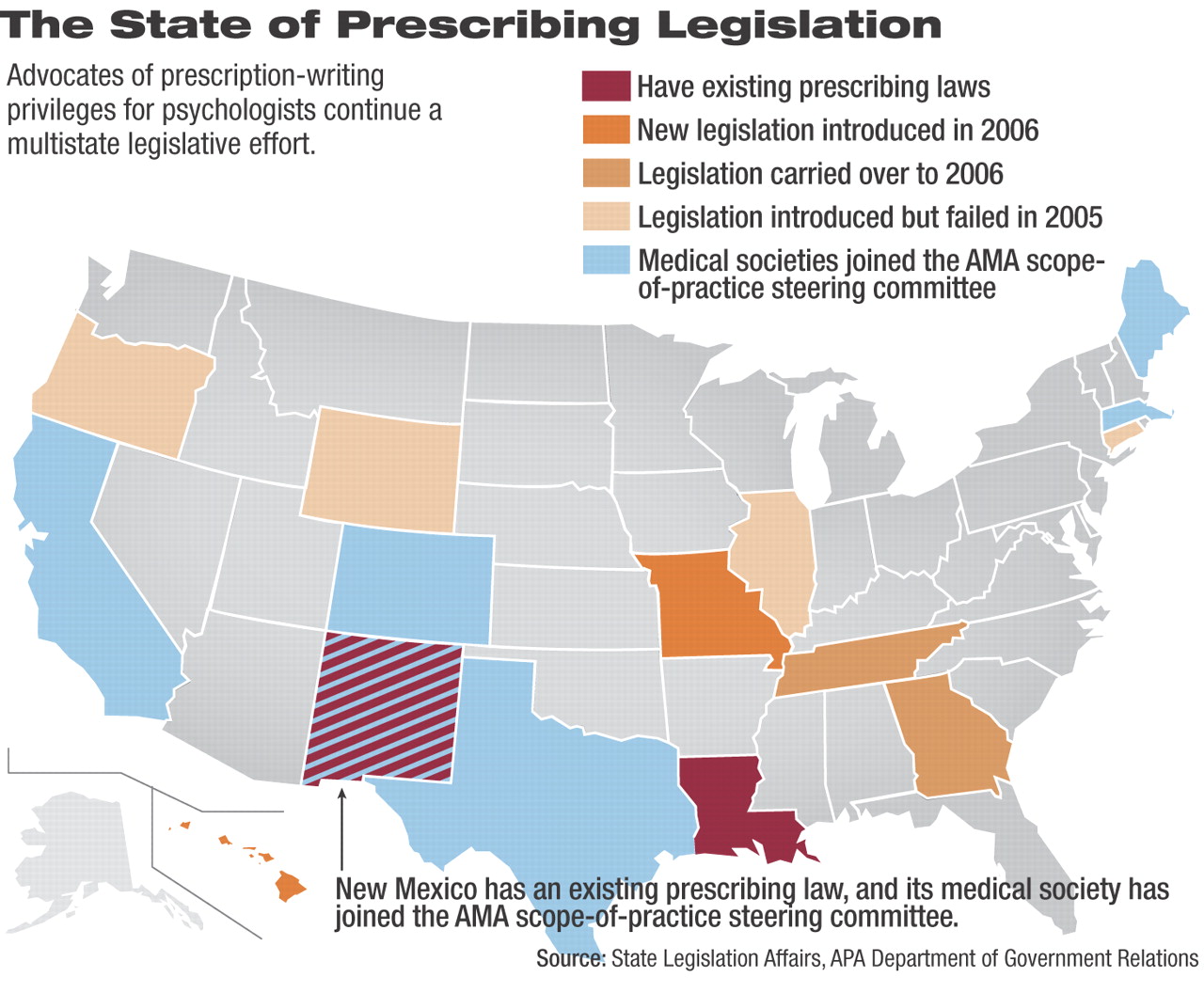

As legislation to grant prescribing privileges to psychologists has proliferated in recent years, state psychiatric organizations have sought greater support from other state and national groups, including APA, to fight such bills.

APA has stepped up its effort to curb such scope-of-practice expansions following the approval in recent years of laws in New Mexico and Louisiana to allow psychologists to prescribe drugs. APA has reached out to other national organizations to help bolster the efforts of district branches and state associations, which are seen as the front line in efforts to fend off such legislation.

“We are not alone in psychiatry with our concerns over the safety of patients when more and more groups of nonphysician health care providers want to expand their practices beyond their training and education,” said James H. Scully Jr., M.D., APA medical director and CEO. “Our members have been intensely concerned about nonphysicians such as psychologists practicing medicine without adequate education and the risks that poses to patients.”

APA's efforts have included increased financial assistance to state groups, advice for district branches on resisting such legislation, and formation of a partnership with the AMA and other specialty societies.

The increased effort was based in part on the proliferation of such bills, which appeared in nine states in 2005. Only legislation in Hawaii and New Mexico—which sought to expand existing psychologist prescription-writing privileges—advanced at all, but bills were offered in Wyoming, Connecticut, Oregon, Tennessee, Georgia, Missouri, and Illinois.

APA's efforts may soon be tested in several states where bills already have been introduced in the 2006 legislative session.

Missouri

A bill (HB 1447) sponsored by state Rep. Dennis Wood (R) would create the classification of licensed prescribing psychologist under the State Committee of Psychologists. The bill would authorize psychologists to write prescriptions for Schedule II psychotropic medicine “or any other psychological treatment or laboratory test as it relates to the practice of psychology.”

The bill would require candidates to have one year of supervision with at least 100 patients consistent with “supervision-preceptorship” models recommended by the American Psychological Association and 300 hours of didactic educational training, and to pass an exam testing their competency.

The bill would require psychologists to form a collaborative practice agreement with a licensed physician for one year to expose them to diagnosis and treatment of medical problems.

The legislation, which did not advance when introduced last year, is not expected to gain much support this year, according to Jill Watson, interim executive director of the Western Missouri Psychiatric Society. She credits APA with helping the district branch stay informed about developments on the issue in other states. APA's message to state groups to form stronger partnerships with their better-funded and more connected state medical societies has already been realized in Missouri, where the state medical society undertakes all of the lobbying against the psychologist prescription bill.

Watson said she hopes to get the society's membership more focused on the issue and to take a more active role in lobbying against the bill.

Georgia

The Georgia Psychiatric Physicians Association (GPPA) is facing the reintroduction of a psychologist prescribing bill introduced at the end of last year's legislative session, said Lasa Joiner, the association's executive director and lobbyist.

The bill (HB 923), sponsored by state Rep. Clay Cox (R), would authorize“ health service provider psychologists” who meet continuing education requirements to prescribe drugs in certain circumstances.

No movement appears likely on the bill, but Joiner said the GPPA is watching that the legislation is not attached to scope-of-practice bills for other allied health professionals that are advancing in the legislature.

The legislation's authors justify it on concerns that psychiatrists are insufficiently dispersed throughout the state to allow timely visits by patients requiring a psychiatric medication. The bill sponsor, who owns a private probation company, said the legislation may help patients such as his clients who live in rural areas. Joiner said he will likely find psychologists are no better distributed around the state.

A better option might be the approval of another bill to allow advanced-practice nurses—such as nurse practitioners—to prescribe under a protocol with a physician, Joiner said. Georgia is the only state that does not allow advanced-practice nurses to write a prescription, though they are allowed to call in a prescription over the phone.

In recent years GPPA has received APA grants to help fund its lobbying effort when hotly contested bills affecting mental health care have arisen. The group also benefits from the Georgia Medical Association's grassroots lobbying campaign, which draws on a pool of more than 6,000 patient-advocates and physicians to pressure legislators.

Their lobbying focus is to help legislators understand the risks and complexities of prescribing medications instead of setting up a choice between psychologists and psychiatrists.

Tennessee

Legislation in Tennessee (HB 479 and SB 723) would give prescriptive authority to psychologists certified by a board of examiners in psychology. It also would require training and education standards set by the board, which would include a psychiatrist representative.

The legislation advanced out of a House subcommittee for the first time last year, said Greg Kyser, M.D., chair of the Legislative Committee of the Tennessee Psychiatric Association (TPA). He credited support from the Tennessee Medical Association and the local branch of the National Alliance on Mental Illness for stopping the bill's progress. An emergency lobbying grant from APA also was critical.

The bill's chances may have faced a setback because one of its former sponsors in the state Senate resigned last year amid a corruption sting by the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation.

In challenging the legislation, Kyser's group focused criticism on the bill's approach to psychologist training, whether it is via a Florida correspondence course or a program at Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey. The TPA is especially wary of programs that appear to inflate training hours or are overseen by general practitioners instead of psychiatrists.

“We try to point out the shortcomings of these programs,” Kyser said.

Hawaii

The Hawaii legislation (HB 539) would authorize “trained and supervised medical psychologists working in federally qualified health centers or other licensed health clinics located in federally designated medically underserved areas” to prescribe psychotropic medications. The prescriptive authority would sunset in 2013. The bill would require psychopharmacological training from an institution of higher learning approved by the state psychology board. It also would require a one-year supervised practicum involving 400 hours treating at least 100 patients with mental disorders. The practicum would be supervised by a “licensed health care provider who is experienced in the provision of psychopharmacotherapy.”

The bill would require psychologist supervision by a “prescribing mental health professional” for two years and then allow candidates to apply for a prescription certificate to prescribe independently. They could not prescribe narcotics. The board of psychology would adopt rules to implement the prescribing rules.

Reintroduced from last year, the bill has not yet advanced. However, the Hawaii Psychiatric Medical Association has received assistance from APA to prepare for the legislation, said Paula Johnson, deputy director for state affairs in APA's Department of Government Relations. The fight has been a long one in Hawaii, where psychologist prescription legislation was first introduced in 1984.

New Mexico

Although there was no legislation introduced in the already concluded 2006 New Mexico legislative session, a bill to expand the 2003 psychologist prescription law advanced in 2005 and is expected again next year, according to the Psychiatric Medical Association of New Mexico (PMANM).

George Greer, M.D., legislative representative for PMANM, said the legislation would expand psychologists' prescribing privileges from those medications that treat mental disorders to those that treat “mental, emotional, behavioral, or cognitive disorders or those that manage the side effects of such drugs.”

The PMANM has received grants from APA to combat psychologist prescribing legislation and fights such legislation through the New Mexico Medical Society, which coordinates combined lobbying by every medical specialty against every scope-of-practice expansion, Greer said.

The support of the statewide group is critical, according to Greer, because it brings more physicians and resources to bear on the issue.

A similar approach is underway nationally, with the AMA unveiling a national partnership of six national medical specialty societies, including APA, and six state medical groups.

“If you get a group of state medical society CEOs and a group of specialty society CEOs together, this issue comes out near the top in terms of problems that they are facing and areas where they need to collaborate and help one another,” said Michael Maves, M.D., AMA's executive vice president and CEO.

Information on psychologist-prescribing legislation is posted for Missouri at<www.house.mo.gov/bills061/bills/hb1447.htm>; Georgia at<www.legis.state.ga.us/legis/2005_06/sum/hb923.htm>; Tennessee at<www.legislature.state.tn.us/bills/currentga/BILL/HB0479.pdf>; Hawaii at<www.capitol.hawaii.gov/site1/docs/getstatus2.asp?billno=HB539>; and New Mexico at<http://legis.state.nm.us/lcs/_session.asp?chamber=H&type=++&number=463&year=05>.▪