Pregnancy does not protect women from the effects of depression, according to a new study, and those who stop taking antidepressants during pregnancy are five times as likely as those who continue taking their antidepressants to relapse.

The study's authors noted that “pregnancy has historically been described as a time of emotional well-being, providing `protection' against psychiatric disorders.” They found, however, that in a sample of about 200 women, the vast majority of those with depression who discontinued their medications experienced a subsequent depressive episode during pregnancy.

The findings appeared in the February 1 Journal of the American Medical Association.

The naturalistic study followed 201 pregnant women from 1999 to 2003 who volunteered to participate in the study and who were enrolled at one of three medical centers specializing in the treatment of psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy. The centers were at Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), and Emory University School of Medicine.

The women were recruited through the hospital clinics, referrals, or advertisements and were considered eligible if they were at least 16 weeks pregnant, had a history of depression prior to pregnancy, were euthymic for at least three months prior to their last menstrual period, and were currently or had recently been taking an antidepressant.

Researchers administered the Structural Clinical Interview's mood module for depression, the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and the Clinical Global Impressions Scale during monthly study visits and tracked subjects' use of antidepressants during pregnancy.

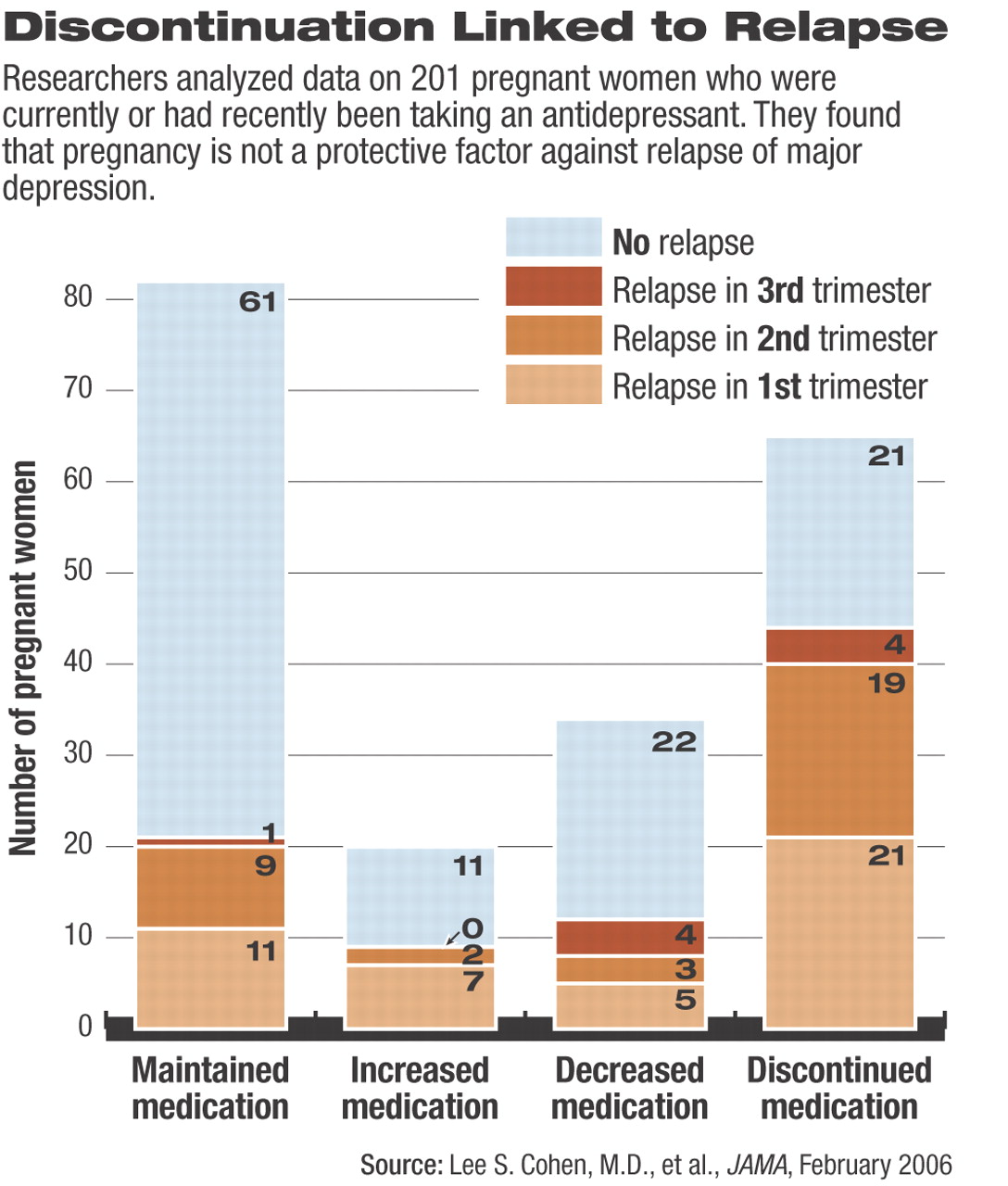

Within the sample, 82 women maintained, 65 discontinued, 20 increased, and 34 decreased their use of antidepressants during the study. The participants were not randomized, and decisions about psychopharmacological treatment were made independently of study participation.

During pregnancy, 86 (43 percent) of the 201 women experienced a depression relapse. This number included 21 women (26 percent) who maintained their medication throughout the pregnancy and 44 (68 percent) who discontinued antidepressant use within the six weeks prior to conception.

The researchers determined that duration of depressive illness (more than five years) and a history of recurrent depressive episodes (more than four episodes) were associated with a significant increase in the risk of depression relapse during pregnancy.

In addition, half of those who relapsed did so in the first trimester of pregnancy and 90 percent by the second trimester.

“The implications for the timing of the relapse are very important,” Lori Altshuler, M.D., told Psychiatric News. Altshuler is one of the study's investigators and director of the Mood Disorders Research Program and a professor of psychiatry at UCLA.

“It was our hope that even if women did relapse, they might not do so until later in pregnancy,” she added. Since drug exposure during early pregnancy “can be associated with vulnerability to developing congenital malformations,” some women may stop their medication “to try to prevent a theoretical risk of malformation, [putting] the mother at great risk for relapse,” she said.

Though it hasn't been studied exhaustively, maternal depression and anxiety may be associated with preterm labor and irritability in newborns, Altshuler noted.

With recent study data associating maternal antidepressant use with a slight risk of pulmonary hypertension and a larger risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome in newborns (see article on

page 25), the decision of whether to continue or discontinue antidepressant use during pregnancy is not an easy one, she acknowledged.

“At this point, I believe that the severity of depressive symptoms the woman has experienced in the past” is an important consideration when deciding to continue or stop antidepressant use during pregnancy, she noted. “No decision is risk free.”

Ideally, women should first discuss with their physicians issues and concerns regarding risk to them and potentially to their infants and make the decision with the family that best serves the interests and concerns of the mother, Altshuler said.

APA Vice President Nada Stotland, M.D., M.P.H., an expert on women's mental health and a professor of psychiatry and obstetrics/gynecology at Rush Medical College in Chicago, agreed. Part of the psychiatrist's job is to ask the patient about how the people closest to her are reacting to her decision about whether to continue with antidepressants while pregnant, Stotland told Psychiatric News.

“We need to protect her from other people's disapproval over whatever she does,” she noted. “We want as much as possible for the patient and her friends and family to be on the same page so that they can be supportive of her.”

Stotland also explained that family support for treatment during pregnancy is “particularly important because we don't want them to blame her for every problem her child may have for years to come.”

The National Institute of Mental Health funded the study.

N Engl J Med 2005 295 499