Ever since 1939, a growing number of studies has demonstrated that the rate of schizophrenia in urban areas is higher than in rural ones. Moreover, the findings have been remarkably consistent across countries and cultures. A dose-response relationship between urbanicity and schizophrenia has been replicated many times. Even when several studies took genetic risk for schizophrenia into consideration, the link between city living and schizophrenia was only slightly attenuated. And—perhaps most provocatively—a city birth and upbringing have been found to precede schizophrenia onset rather than the other way around.

Now a British study published in the March Archives of General Psychiatry adds ammunition to the argument that city living somehow sets the stage for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. The lead author was James Kirkbride, a Ph.D. research student in the University of Cambridge Department of Psychiatry.

The scientists tracked, over a two-year period, more than 1.5 million individuals living in three areas of England to determine who developed psychosis associated with schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder for the first time. In other words, data on individuals aged 16 to 64 who visited mental health services in the three areas during the two-year study period because of a probable psychosis were evaluated further by a panel of psychiatrists to determine whether they met DSM-IV criteria for psychosis. The psychiatrists were not only blind to subjects' ethnicity, but came from various ethnic backgrounds themselves.

The three geographic areas included in the study were Bristol, a largely prosperous city, but also with a number of homeless people; Southeast London, exclusively urban and with some of the highest violent crime rates in England; and Nottingham, which is a mixture of urban, suburban, and rural environments.

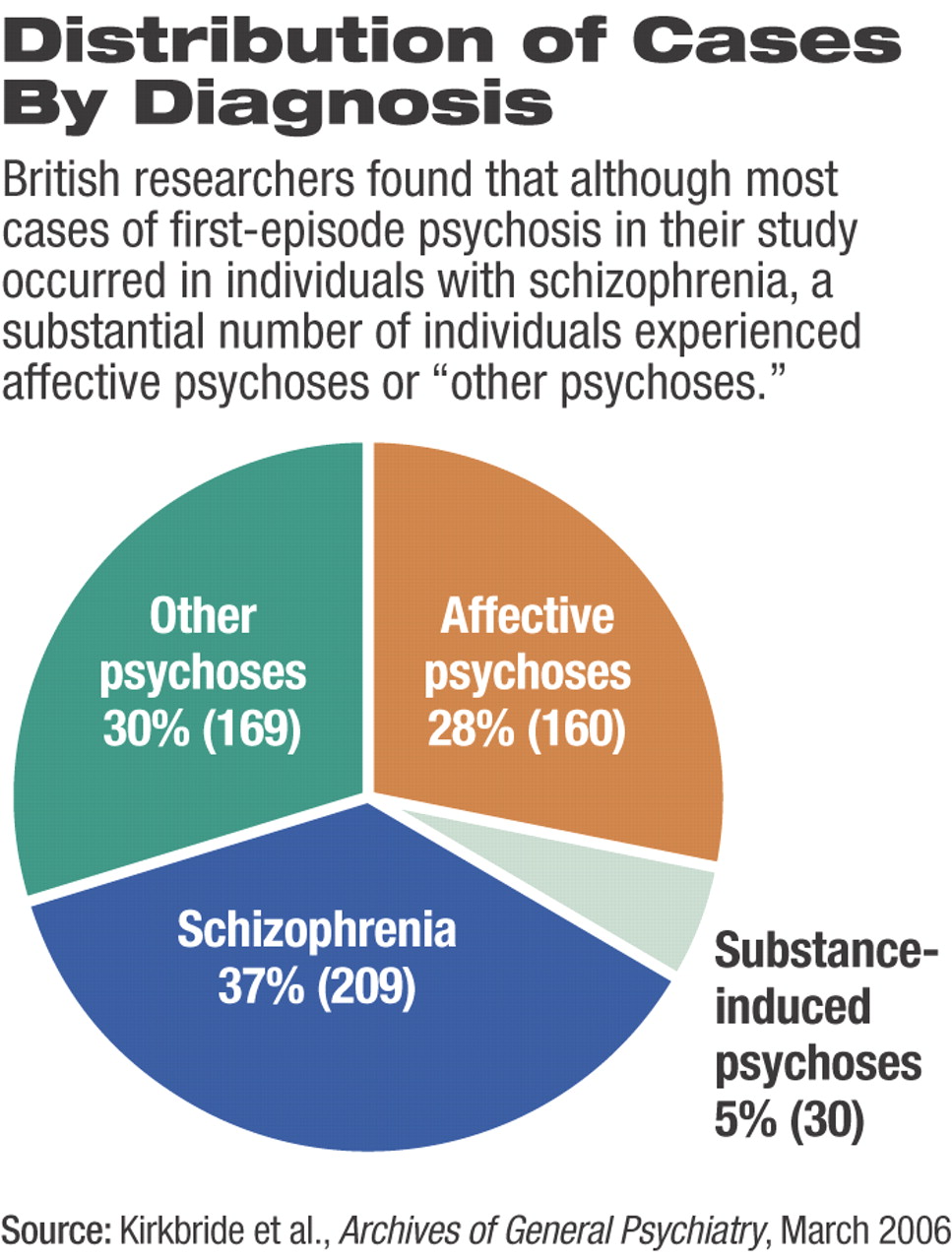

In all three of these areas, and over the two-year study period, 568 individuals were found to have had a first-episode psychotic disorder. Thirty-seven percent were diagnosed with schizophrenia, 30 percent with other nonaffective psychoses, 28 percent with affective psychoses, and 5 percent with substance-induced psychoses (see chart).

The investigators then examined the gender, age of onset of illness, and ethnicity of these 568 individuals. Sixty-nine percent of those with schizophrenia and those with substance-induced psychosis were men, but for other psychoses, gender differences were more modest (men, 54 percent). Over half of all cases of affective psychosis were women (52 percent).

The highest incidence of first-time psychosis for men occurred between the ages of 20 and 24 years, whereas the highest incidence for women took place earlier, between 16 and 19 years.

Incidence of psychosis was about four times greater in persons belonging to non-British minority groups than in persons who were British and white. The minority groups hailed from Africa, the Caribbean, India, Ireland, and other European countries. Indeed, even when age of onset of illness, gender, and place of residence were taken into consideration, the rate of psychosis was still three times higher in non-British minority individuals than in white British individuals.

Finally, the investigators found that place of residence was linked with developing psychosis even when ethnicity, age of onset of illness, and gender were accounted for. For all psychoses, the rate in Southeast London remained significantly higher than in either Bristol or Nottingham.

“There is significant and independent variation of incidence of schizophrenia and other psychoses in terms of sex, age, ethnicity, and place,” Kirkbride and his team concluded in their study report.“ This confirms that environmental effects at the individual, and perhaps neighborhood, level may interact together and with genetic factors in the etiology of psychosis.”

Kirkbride told Psychiatric News, “We weren't surprised that we observed heterogeneity in incidence rates by place, age, or sex for schizophrenia, as there is now a large body of evidence to suggest that the disorder varies on these dimensions. The findings of differences by place have also been observed elsewhere in Europe. The surprising thing is that this is not well known; psychiatric textbooks say that the incidence of schizophrenia is the same everywhere. This myth has hindered causal research for too long. By showing heterogeneity in several domains in a single study, we hope to debunk the myth, once and for all.”

“This is an important study that advances knowledge of environmental effects in the incidence of broadly defined psychosis,” William Carpenter Jr., M.D., director of the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center and a schizophrenia authority, told Psychiatric News. “The broad definition is important since genetic and environmental risk factors for psychosis are likely to be shared across current diagnostic classes.”

“This is a wonderful study, clearly showing that certain environmental effects—most likely interacting with genetic risk—predispose to psychosis,” Jim van Os, M.D., Ph.D., said.

Van Os is a professor of psychiatry at Maastricht University in the Netherlands and one of the scientists in the forefront of exploring the urban-schizophrenia connection. For example, he pointed out, the investigation“ provided direct correction for ethnic group, an important confounder; included affective and nonaffective psychosis (a much more common group than schizophrenia alone), and was based on direct clinical, interview-based diagnoses in real patients (rather than register-based systems).”

Precisely what it is about city living that might predispose people to schizophrenia, however, is not known. As van Os pointed out in the September 8, 2005, Schizophrenia Bulletin, studies on the subject to date have largely ruled out some of the more egregious suspects such as obstetric complications, neuropsychological impairment, infectious diseases, traffic, air pollution, and social isolation. However, low socioeconomic status and psychological stress at the neighborhood level may be critical risk factors, Kirkbride and his group proposed. In fact, persons who develop schizophrenia are especially sensitive to stress, a study by van Os and his colleagues found (Psychiatric News, May 16, 2003).

In any event, “the importance of gene-environment interactions is a given,” Carpenter asserted. “The number of possible genes and possible environmental factors is very large, and timing of effect for each may range between early brain development to later life.”

The study was funded by the Medical Research Council in London and the Stanley Medical Research Institute in Bethesda, Md.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005 63 250