Mothers with depressive symptoms in the months after giving birth are less likely to read to, talk to, or play with their newborns than mothers who are not depressed, according to a new study.

Screening mothers of newborns could identify women with depressive symptoms and allow pediatricians to counsel them in good parenting practices and refer them to mental health professionals to treat their symptoms, wrote Kathryn Taaffe McLearn, Ph.D., and colleagues in the March Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine.

At the same time, pediatricians who inquire about parenting practices could also gather valuable clues about the mother's mood status.

“Further efforts are needed to ensure that linkages exist between adult and pediatric systems of care,” said the authors. “Such an approach has the potential to foster positive parenting, child health and development, and family well-being.”

The researchers based their analysis on data gathered from 15 sites (six randomization sites and nine quasi-experimental sites) as part of the National Evaluation of Healthy Steps for Young Children. Healthy Steps is a model of pediatric care incorporating child development specialists and services in pediatric practices. Mothers in the program completed forms at enrollment and a follow-up telephone interview at two to four months.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to assess symptoms. Of the 5,565 families enrolled, 4,874 provided symptom data and completed the survey. About 17.8 percent of the mothers reported depressive symptoms by scoring 11 or above on the 14-question modified CES-D.

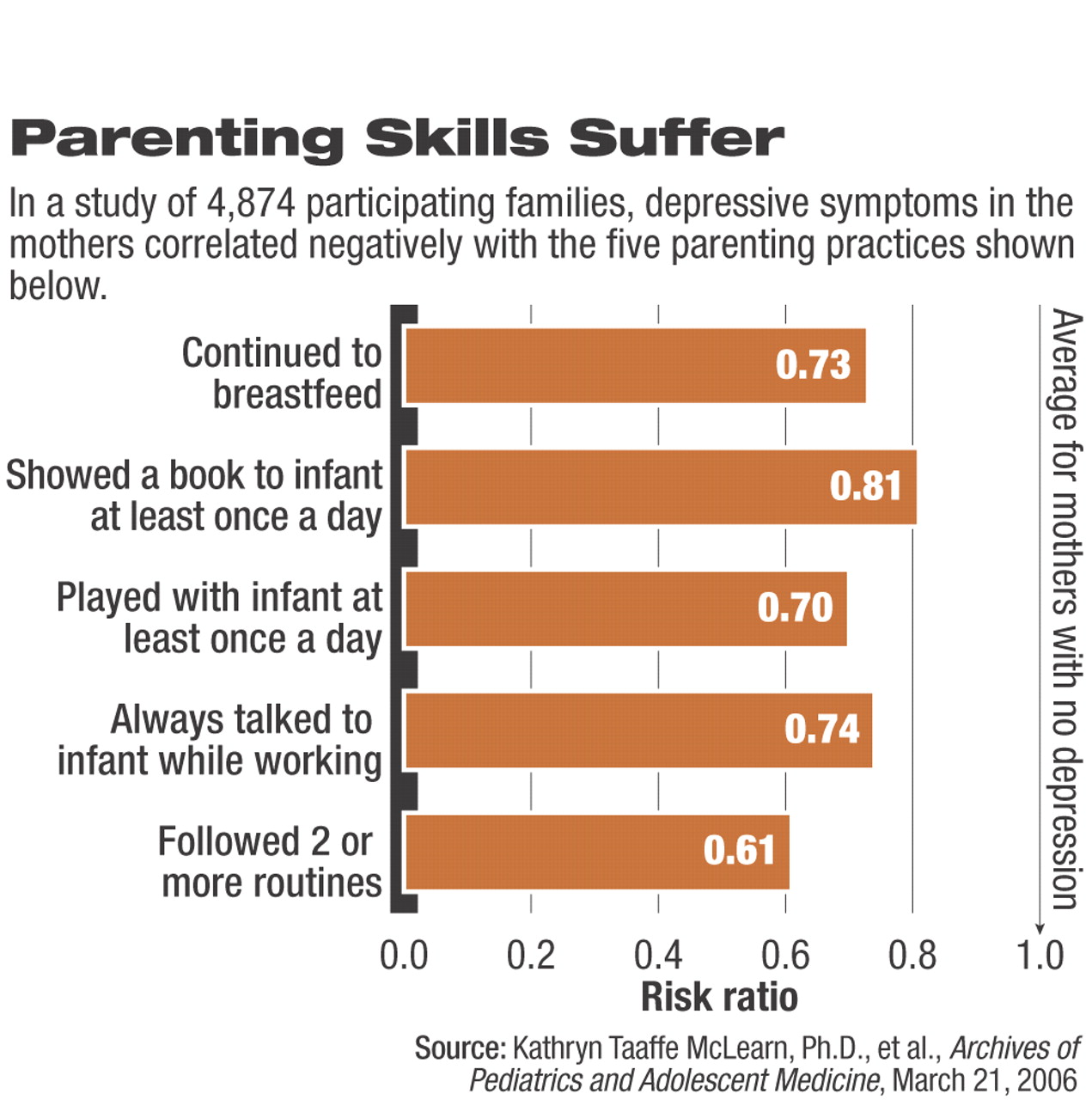

The researchers then compared the self-reported safety, feeding, and developmental practices with symptom status. After adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic factors, five practices remained significantly associated with depressive symptoms.

Depressed women less often used parenting practices believed important for a child's development. They were less likely to read a picture book to their child, play with the infant at least once a day, talk to the baby while working around the house, and follow two or more mealtime, naptime, or bedtime routines (see chart).

Depressive symptoms appear to reduce parenting practices that demand greater interaction with infants, wrote McLearn and colleagues.

More symptomatic women were also less likely to continue breastfeeding their babies than were women without depressive symptoms. However, both groups of women were equally likely to give cereal, water, or juice to their babies before four months of age despite American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations not to introduce them until later.

The researchers were limited to the two practices selected by the original study as markers for safety: putting children to sleep on their backs to reduce risk of sudden infant death syndrome and turning down the temperature of the household's hot-water heater to prevent burns. Depression symptoms were not associated with these two practices. However, they may not be useful indicators of mood, thanks to factors other than depression, said Linda Chaudron, M.D., M.S., an assistant professor of psychiatry, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Rochester.

“Mothers have been bombarded with reminders to put babies to sleep on their backs so that it's become routine now,” said Chaudron in an interview. Similarly, water temperature may reflect socioeconomic patterns, if young, vulnerable mothers are more apt to live in apartment buildings.

“Yes, there likely is a `ceiling effect' with regard to sleep position given that 88 percent of the families used the correct sleep position for their young infants,” said co-author Cynthia Minkovitz, M.D., M.P.P., in an interview. “We have no information regarding access to water temp controls. The lack of association of depressive symptoms and safety practices in adjusted analyses, unlike prior studies, may be due in part to the diversity of our sample and our ability to adjust for other characteristics of families.”

Demographic factors may also have played a role in the study. When compared with nonrespondents, mothers who completed the survey were more likely to be white, non-Hispanic, married, high school graduates and older than 20 years and report that the baby's father was employed. However, mothers reporting depressive symptoms were more likely to be from minority groups, younger than age 20, Hispanic, and not living with the child's biological father and have less than a high school education and a low income.

Besides the direct results of their study, the researchers said its design demonstrates the validity of maternal reports as a source of data,“ without having to use expensive direct-observation methods.”

“Are pediatricians asking questions about these practices?” asked Chaudron, who agreed with McLearn and colleagues that pediatricians should be encouraged to screen mothers for depression. “They're nice, practical questions to ask new moms, and they could raise red flags for both mothers and babies.”

One obstacle to care is how pediatricians respond to the red flag, said Chaudron. “We still don't know the best way for pediatricians to connect these women—who are not their patients—to mental health care or to their own [health care] providers.”

The risks and benefits of treatment options for depressed women after they have given birth should be carefully discussed, she said. Low levels of antidepressants can be carried through the mother's milk to a nursing child, but there have been few reports of problems from that exposure, she said. Some women may prefer psychotherapy to medication, but as the current study shows, symptomatic mothers can adversely affect a baby's development, so some treatment is usually indicated.

McLearn and colleagues suggested that pediatricians' anticipatory guidance to mothers with depressive symptoms can foster improved parenting practices and thus the child's health and development.