Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may be at risk for alcohol-use disorders when they reach adolescence, according to new findings from University of Pittsburgh researchers.

“We found that once children diagnosed with ADHD became teenagers, they were more likely than those without ADHD to drink heavily or to have diagnosable alcohol use disorders,” Brooke Molina, Ph.D., told Psychiatric News. The results of the study she and her colleagues conducted appear in the April Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research.

The researchers wanted to test whether there was an association between childhood ADHD and later alcohol use and whether conduct problems in childhood could predict risk for alcohol problems among those who had been diagnosed with ADHD as children.

They interviewed 364 adolescents and young adults enrolled in the Pittsburgh ADHD Longitudinal Study, all of whom had been diagnosed with ADHD as children, and 240 age-matched controls who had never been diagnosed with ADHD.

The 364 teenagers and young adults had initially been diagnosed with ADHD at the Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic in Pittsburgh between 1987 and 1996. Most were in elementary school at the time.

Researchers recruited subjects in the control group from the Pittsburgh area between 1999 and 2001 through several large pediatric practices and advertisements placed in newspapers and at local colleges.

Molina and her colleagues evaluated these participants either as adolescents (11 to 17 years old) or young adults (18 to 25 years old) for the presence of alcohol use disorders as well as on a number of drinking measures, including the frequency and quantity of drinking.

They also assessed whether those who had been diagnosed with ADHD as children had comorbid conduct disorder, and whether those who were adults at the time of the follow-up evaluation had comorbid antisocial personality disorder.

Researchers used the parent and teacher Disruptive Behavior Disorder Rating Scale to determine whether adolescents had conduct disorder. To determine whether young adults had antisocial personality disorder, parents and subjects completed the Antisocial Personality Disorder portion of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

Molina noted that for adolescents who had previously been diagnosed with ADHD, the risk for heavy drinking or drinking problems began at around age 15. For example, the teens aged 15 to 17 with childhood ADHD reported being drunk an average of 14 times in the previous year versus 1.8 times for those without an ADHD diagnosis.

Approximately 14 percent of those who had been diagnosed with ADHD were diagnosed upon follow-up with alcohol abuse or dependence, and none of the 15- to 17-year-olds without childhood ADHD had alcohol problems.

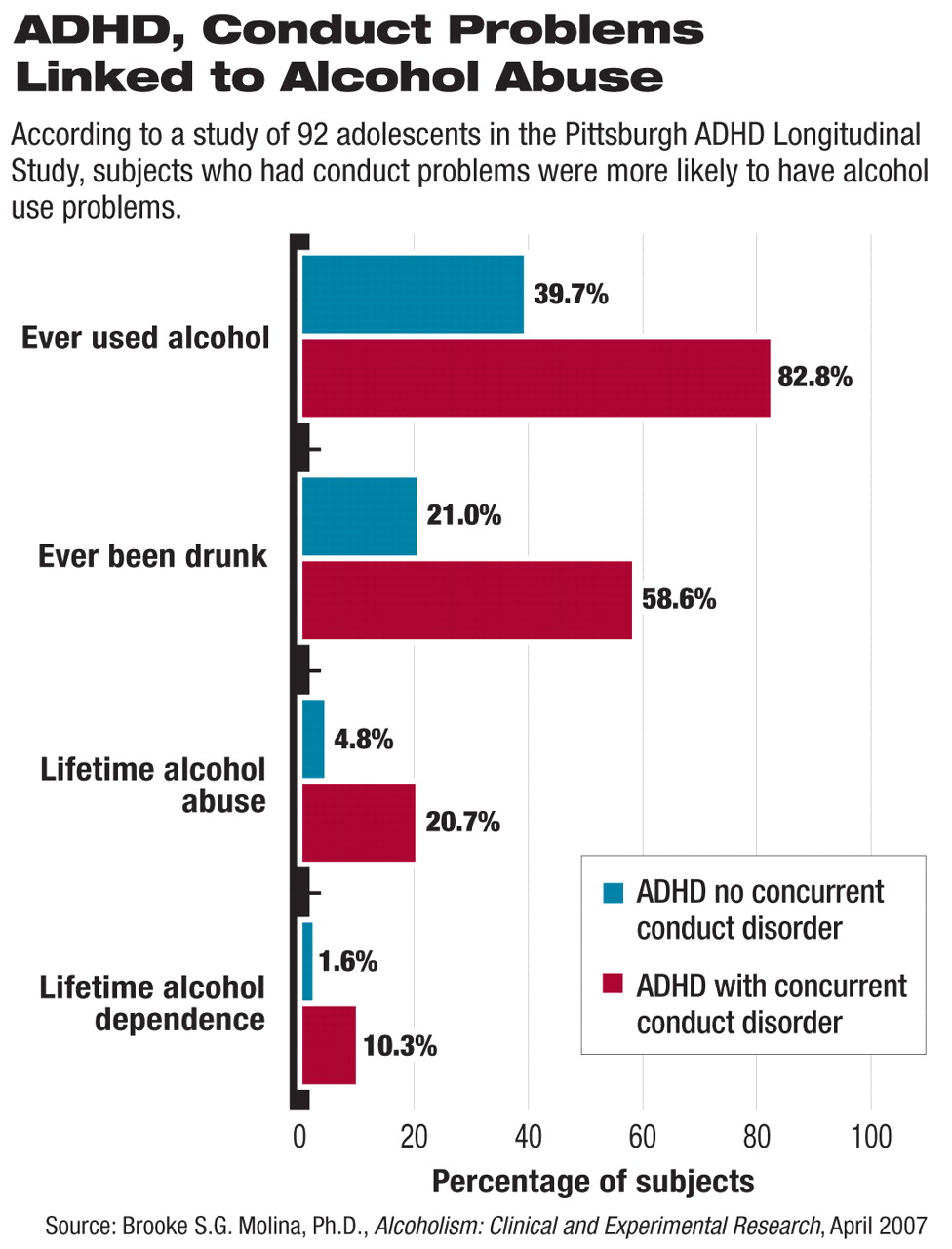

The researchers also found that those with ADHD and co-existing conduct disorder as adolescents had significantly higher rates of alcohol abuse than did those with ADHD alone: for instance, 20.7 percent of those with ADHD and concurrent conduct disorder as adolescents were diagnosed with alcohol abuse, compared with 4.8 percent of those with ADHD alone.

Molina also found that 10.3 percent of adolescents with ADHD and concurrent conduct disorder met criteria for alcohol dependence, compared with 1.6 percent of those with only ADHD.

For those assessed in early adult hood (aged 18 to 25), Molina found that 42 percent of those with ADHD and antisocial personality disorder met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence as compared with less than 20 percent of those with only ADHD.

Molina pointed out that children with ADHD have a higher risk of developing both adolescent conduct disorder and alcohol problems, even when they don't have serious conduct problems in childhood. This means that all children with ADHD should be considered potentially at risk, especially if alcoholism runs in the family. The importance of familial alcoholism as a risk factor is described in the researchers' second paper in the same issue of Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research (see

“Parents' Alcohol Use: Danger Signal”).

Molina acknowledged that in general most people tend to drink most heavily between the ages of 18 and 25, so she and her collaborator William Pelham, Ph.D., hope to follow the sample into their 30s to examine whether drinking problems decline with age, as they do in the general population.

“The message to most of us in the ADHD field is that ADHD persists into adolescence for about two-thirds of youth, so parents and practitioners need to stay involved. Among other things, heavy drinking is a possible outcome for a substantial minority of these youth,” Molina noted.“ This seems to be a disorder that [even with treatment] stays in place. So we need more research on how to help these kids once they reach adolescence and adulthood.”

The study received funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

An abstract of “Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Risk for Heavy Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorder Is Age Specific” is posted at<www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00349.x>.▪