As obesity becomes a problem generating increasing levels of concern in various countries, the psychological ramifications of the condition are also receiving more attention.

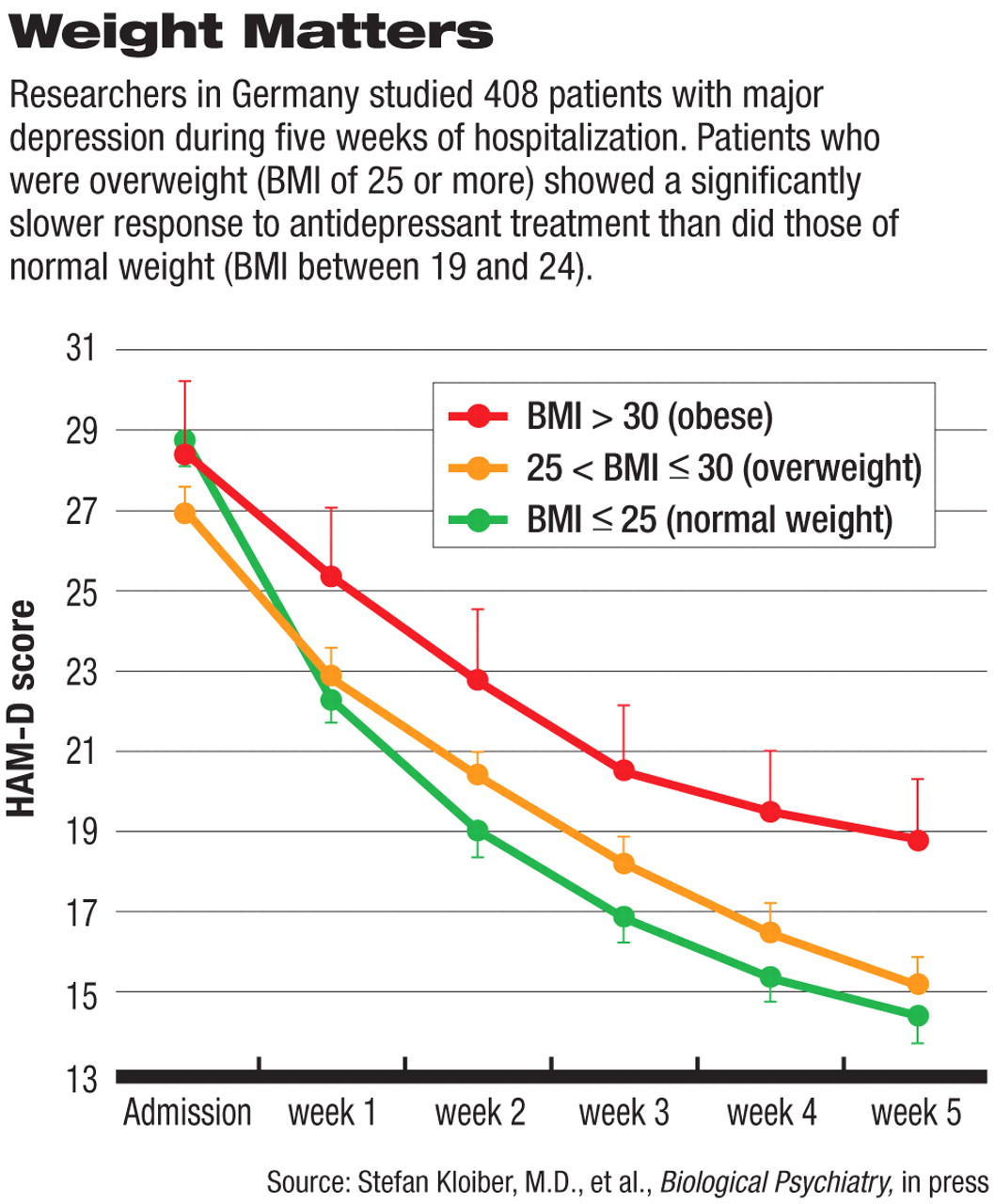

For example, Stefan Kloiber, M.D., a psychiatry resident at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich, Germany, and colleagues studied 408 inpatients with a DSM-IV-diagnosed major depression over a five-week period. They found that these patients had a significantly greater body mass index (BMI) than healthy control subjects. They also found that of the depressed patients in their cohort, those who were overweight (with a BMI of 25 or greater) showed a significantly slower response to antidepressant treatment than did those of normal weight (with a BMI between 19 and 24).

“Our findings suggest that overweight and obesity characterize a subgroup of major depressive disorder patients with unfavorable treatment outcome,” they concluded in their study report, which is in press with Biological Psychiatry.

“This study confirms earlier findings that depression is associated with obesity,” Gregory Simon, M.D., a psychiatrist and researcher at Group Health Cooperative in Seattle, told Psychiatric News. Indeed, in his own study of some 2,300 women, he found that major depression was twice as prevalent among women with a BMI greater than 30 than in women with a BMI less than 30 (Psychiatric News, September 16, 2005). “[But] what's new here,” he continued, “is the finding that obesity predicts poorer response to depression treatment.”

Why this is so, however, is open to some speculation. Kloiber and his group favored a biological explanation because they found that in their overweight depressed patients, as compared with their normal-weight depressed ones, there was not just a slower response to antidepressant treatment, but less improvement in two physiological functions often impaired in depressed persons—attention and regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis.

But if biology underlies overweight depressed individuals' response to antidepressants, what factors might be involved? Cytokines, adipok ines, and leptin, Kloiber and his team suggested. Cytokines are cell-to-cell signaling proteins. Adipokines are a group of cytokines secreted by adipose tissue. Leptin, a protein hormone produced by fat cells, is involved in body-weight regulation by acting on the hypothalamus to suppress appetite and to burn fat stored in adipose tissue.

The reasons why they suspect cytokines and adipokines are implicated is because cytokines and adipokines are known not only to play an important role in the pathophysiology of obesity, but to interact with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis and neurotransmitter systems. They suspect that leptin might be involved because it is known, besides influencing appetite and weight regulation, to impact learning, memory, and some other central-nervous-system functions.

Although Kloiber and his team focused on biological explanations for the poorer antidepressant response of overweight depressed individuals, “we should also consider psychosocial explanations,” Simon pointed out.“ Obesity leads to a significant burden of self-blame, social isolation, and activity limitations, all of which may contribute to depression. So we might think of obesity as a major, ongoing psychosocial stressor that reduces the likelihood of recovery from depression.”

One of this study's findings, however, should give depressed overweight people a psychological lift. It found that depressed overweight subjects gained significantly less weight while taking antidepressants than did depressed subjects of normal weight. The researchers were surprised by this finding because, as Kloiber explained to Psychiatric News,“ many clinical psychiatry experts consider obese patients to be at higher risk for additional weight gain during psychopharmacological therapy compared with normal-weight patients.”

The study was funded by the Max Planck Society.