Girls who were sexually abused are more likely to become obese than those who were not abused, but that difference does not show up until early adulthood, according to a report in the July Pediatrics.

Clinicians should not only treat young victims of abuse but should maintain a close watch on increasing body mass index (BMI) at least into their patients' early 20s, said the researchers.

However, they do not argue that there is a causal link between sexual abuse and obesity or that obesity is an inevitable outcome of abuse.

“We simply wish to underscore the need for systematic study of the mechanistic and mediating processes that would help to explain the connection between childhood abuse and late obesity,” wrote Jennie Noll, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychology at the Cincinnati Children's Medical Center and the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, and colleagues.

The researchers studied 84 sexually abused female subjects, aged 6 through 16, who had been referred by child protective services in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area. Median age at onset of abuse was 7.8 years.

These subjects were compared with 89 never-abused female subjects recruited from the same neighborhoods and matched for demographic factors.

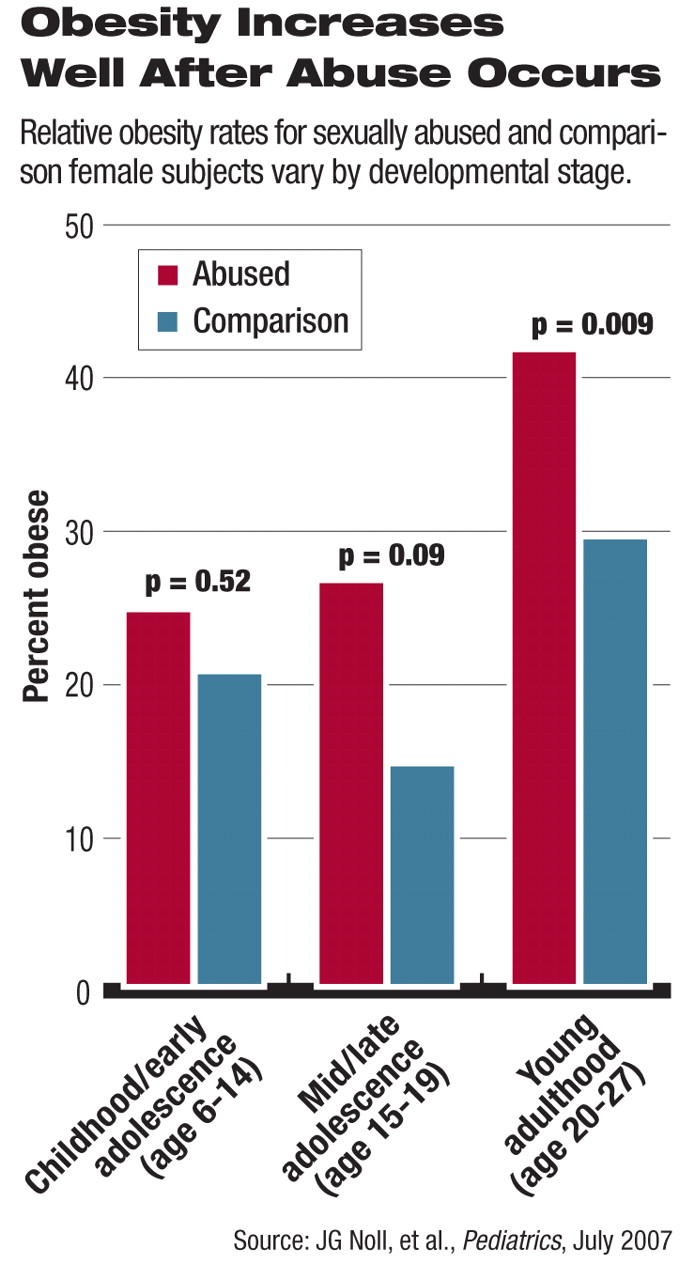

The study began in 1987, and subjects were assessed at six time points, ending in 2006. Obesity status was determined for three stages of development: childhood/early adolescence (ages 6 to 14); middle to late adolescence (ages 15 to 19); and young adulthood (ages 20 to 27). Twelve abused girls and 10 comparison subjects who were obese at baseline were eliminated from analysis.

In childhood or adolescence, obesity rates between the two groups were not significantly different, but in their 20s, 42 percent of the abused and 28 percent of the comparison subjects were obese (defined as BMI of 30 or higher after age 20). Thus, while obesity rates at about age 11, at baseline, were similar, by mean age 24, women with documented histories of sexual abuse were more than twice as likely to be obese as their non-abused peers.

“These results provide some of the first prospective evidence that childhood sexual abuse may place female individuals at inordinately high risk for developing and maintaining obesity,” the researchers said. Previous studies have retrospectively found correlations between abuse and later obesity but this is the first such prospective study, they noted.

It is unlikely that the general rise in the prevalence of obesity in the United States over the last several decades might account for the difference, Noll told Psychiatric News. “The comparison group follows the CDC's [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's] growth trajectory closely.”

She was careful not to draw an oversimplified connection between the two conditions. There might be a biological component, in that abuse is known to dysregulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, whose hormones are involved in fat deposition and metabolism.

However, the nexus of obesity and abuse does not occur in a vacuum. A family culture of dysfunction may be expressed in overeating, she said:“ The connections should be examined further.”

Abuse also is a form of control by adults over the child victims, and overeating may be a way for abused children to gain some control of their own, she said. Others have argued that being overweight is a way to make oneself unattractive and ward off undesired attention.

Noll rejects any idea that there is a one-to-one relationship between obesity and child abuse.

“But if practitioners know of a history of sexual abuse, they should be cognizant of possible problems, especially at important developmental milestones,” she said. Those milestones might include a first adult relationship, marriage, childbirth, or when their own children reach the same age at which they were abused. Abused children don't need to be monitored continuously, but these life stressors may lead to behaviors such as drinking, smoking, drug use, or promiscuity that have serious health consequences.

Pediatricians treating abused girls should closely track BMI changes through development and intervene as necessary, the researchers suggested.

“Childhood-abuse treatment extending beyond the acute phases of recovery or that is revisited throughout development may improve health outcomes for abuse survivors,” they said.