There are two types of autism—an early-onset type and a later-onset regressive type—retrospective studies have suggested. When infants have the former, their level of complex babbling, word production, and declarative pointing are lower than those produced by typically developing children at a year or so of age. When infants have the latter, they behave essentially like normally developing infants during the first year or so of life, but by age 2, use significantly fewer words, respond to their names much less often, and look at people much less often than typically developing children do (Psychiatric News, October 7, 2005).

Now a prospective study published in the July Archives of General Psychiatry essentially confirms the above findings. The study was headed by Rebecca Landa, Ph.D., of the Center for Autism and Related Disorders at Johns Hopkins University.

The study included 107 infants at a high genetic risk for autism, since they were siblings of children already diagnosed with autism, and 18 infants at a low genetic risk for autism, since they had no known family history of the disorder.

All 125 infants were evaluated for social abilities, communication abilities, and play behavior from the ages of 14 months to 3 years. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile, the Mullen Scales of Early Learning, and the Preschool Language Scale were used for the evaluations.

The researchers also recorded their impressions of whether the infants, at 14, 24, and 30 or 36 months, had autism. DSM-IV criteria for autism or pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified were followed as closely as possible. At age 14 months, for example, the DSM-IV criterion for autism of “failure to develop peer relationships” was not applicable, so the researchers substituted impairment in social interactions combined with stereotypic behavior for that criterion.

These impressions, combined with Autism-Diagnostic Observation Schedule algorithm criteria for autism or autism spectrum disorder, were then used to decide which of the infants had autism. Sixteen infants were diagnosed with early-onset autism, that is, they were determined to already have it by 14 months. Another 14 infants were diagnosed with later-onset autism, that is, they were determined to have acquired it between 14 months and age 2. The remaining 95 infants were determined to not have autism.

The investigators then used the formal assessments they had made of each group's behavior to compare the groups on social development, communication development, and play development.

For example, at 14 months of age, the early-onset group was significantly poorer in shifting gazes, made significantly fewer gestures, and used significantly fewer consonants than the nonautism group did. By two years of age, the early-onset group continued to perform significantly worse than the nonautism group did on all but four variables.

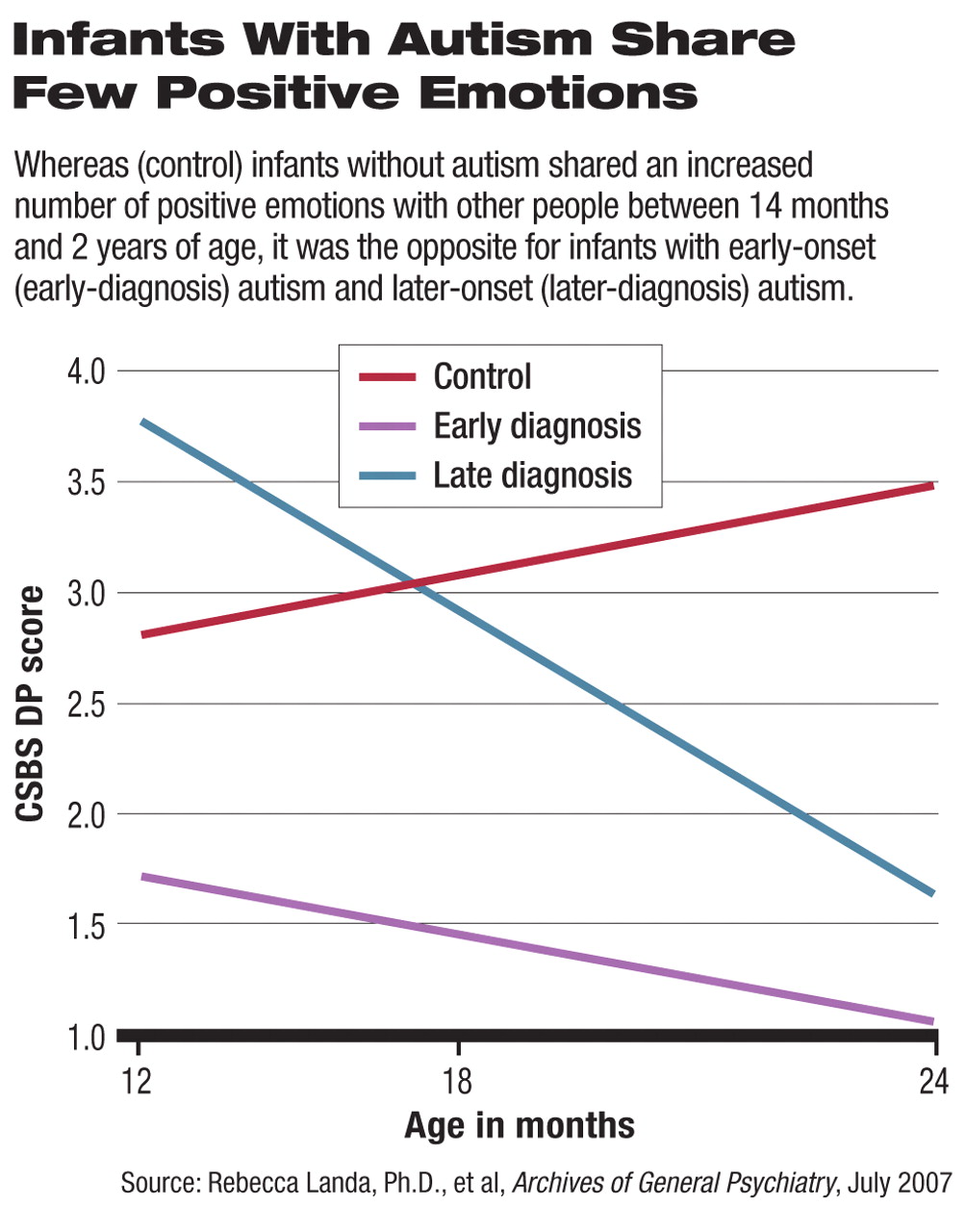

In contrast, at 14 months of age, the later-onset group differed from the nonautism group in only one respect—making significantly fewer shifts in gaze. During the next few months, though, the later-onset group slowed in its acquisition of consonants, syllables, words, and word combinations, and even decreased its display of shared positive affect and its use of gestures. By age 2, it showed significantly less shared positive affect and made significantly fewer gestures than the nonautism group did.

“This is, to our knowledge, the first prospective study of autism spectrum disorder from 14 to 36 months of age to document distinct patterns of social, communication, and play development associated with early and later diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder,” Landa and her colleagues concluded in their study report. “These findings support the retrospective findings of significantly disrupted development by the first birthday in some children with autism, but not others.”

Since autism is rarely diagnosed before age 3, these findings may spur the development of reliable and validated instruments to diagnose autism as early as the first or second birthday. In fact, a University of Michigan researcher is already preparing a version of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule for children aged 2 and younger, the researchers reported.

The results also underscore the urgency of determining whether early interventions might help infants with autism and offer new insights into which types of interventions might help. For example, teaching not only visual-spatial skills, vocabulary, and gross-motor imitation skills, but also how to communicate with gestures, might be of benefit.

“This is the first study to demonstrate that a. .diagnosis of autism can be made in infants as young as 14 months of age,” Geraldine Dawson, Ph.D., an autism authority and director of the University of Washington Autism Center, told Psychiatric News. “They found two different patterns of onset, however. Some children showed clear symptoms by 14 months of age, whereas others did not show the full syndrome until a year later. Pediatricians should thus assess at-risk infants at both 1 and 2 years of age to make sure that some children are not missed.”

“One of the most exciting implications of this study,” she continued, “is that we should be able to begin interventions for infants with autism by age 1, perhaps even earlier for at-risk infants. We may be able to have a greater impact on brain development when interventions are started in infancy. This offers hope for a more positive future for children with this disorder.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.