The rate of child maltreatment in families of enlisted soldiers was 42 percent higher when military spouses were off at war than when they were at home, according to a study covering all substantiated reports of child maltreatment among U.S. Army families worldwide between September 2001 and December 2004.

“The findings confirm the need for supportive and preventive services for Army families during times of deployment,” wrote Deborah Gibbs, M.S.P.H., of the child and families program at RTI International in Research Triangle Park, N.C., and colleagues in the August 1 Journal of the American Medical Association. The U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command provided funding for the study.

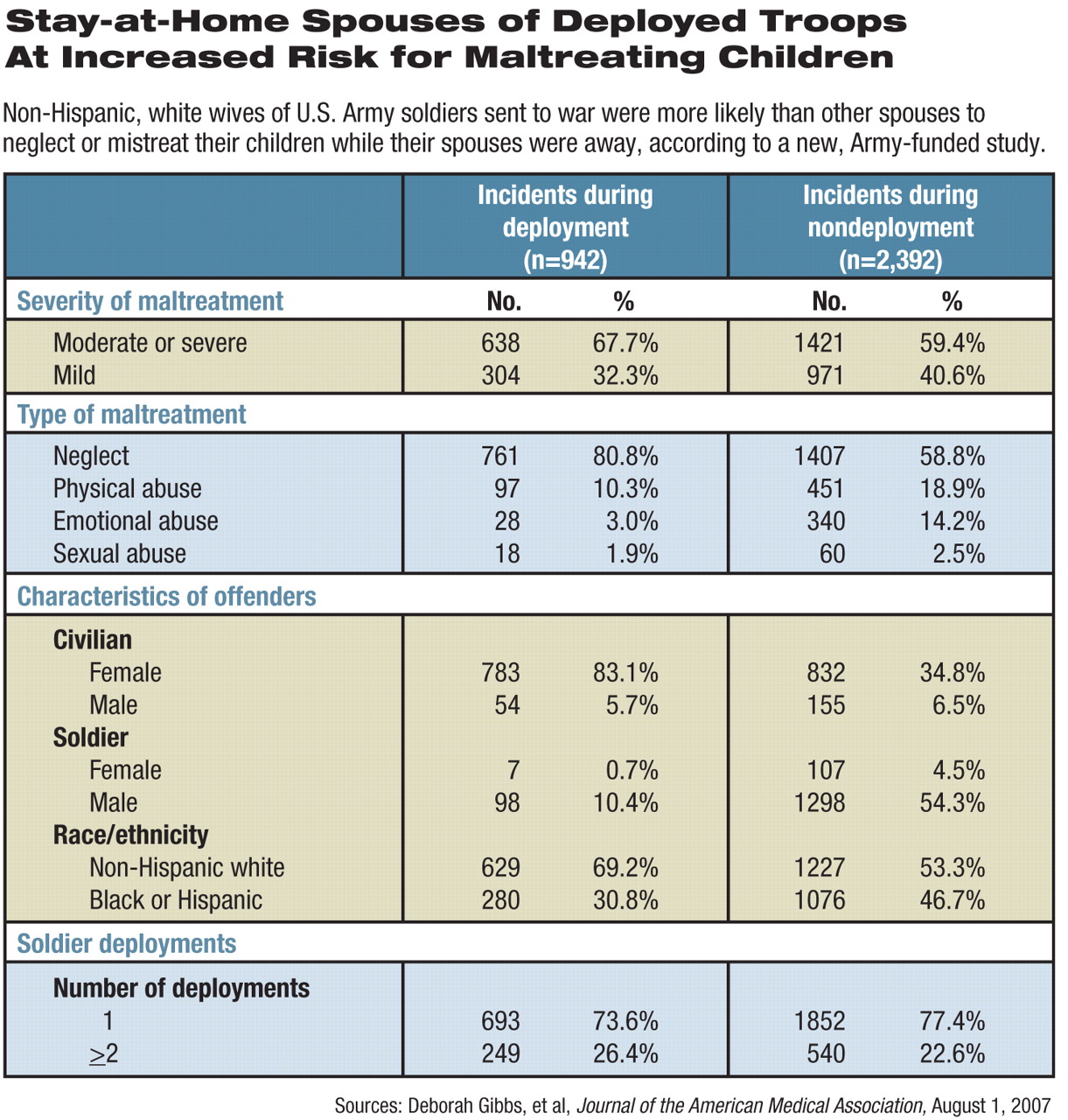

The study linked Army human-resource data with information from the Army Central Registry on confirmed incidents of child maltreatment or spousal abuse reported by Army medical, social-service, educational, and law-enforcement personnel. Overall, there are 1.1 million children younger than age 18 in U.S. military families. During the 40 months covered by the study, 1,858 parents in 1,771 families of enlisted soldiers neglected or abused their children, in a total of 3,334 incidents involving 2,968 children. Of those, 942 incidents occurred during deployments.

Among the families excluded from the study because of likely differences in families' experiences of deployment and small sample size were 156 families in which the soldier and civilian parent were not married.

During deployments, rates of child maltreatment rose for female civilian parents but not for male civilians, and rates were greater for non-Hispanic whites than for blacks or Hispanics, said the researchers. Children between the ages of 2 and 12 were more likely to be mistreated during deployment than those younger or older.

Female civilian parents were twice as likely to abuse a child physically and almost four times more likely to neglect a child when male soldiers were deployed than at other times, said Gibbs and colleagues. Sexual abuse rates remained almost the same.

“We see here the classic profile of child neglect,” Gibbs told Psychiatric News. “Parents who are suffering from depression and need help the most are the least likely to seek help or accept services.”

The researchers found similar increases in maltreatment rates in both lower and higher (sergeant or above) enlisted pay grades.

The study did not measure initial rates of maltreatment, only the difference between families who were dealing with deployment and those who were not.

Both single and multiple deployments affected child maltreatment rates, but more than one deployment did not appear to be associated with worse rates of maltreatment beyond those seen in families with soldiers deployed once.

That may suggest some resiliency, if validated by future research, said Stephen Cozza, M.D., associate director of the Center for Traumatic Stress and a professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md., in an interview.

“This is the first piece of data-driven analysis I've seen that looks at the effects of multiple deployments,” he said. “However, based upon the statistical measures used, we cannot draw any conclusions about the relative change in risk of child maltreatment between families in which a single or multiple deployment has occurred. Many variables could be impacting these results.”

Not only deployment but the increased pressures of training and other operations in shorthanded units during wartime also create stresses for families, said Cozza.

The late-2004 cutoff of Gibbs's study should prompt caution regarding the impact of multiple deployments, said Joyce Raezer, M.A., chief operating officer of the National Military Families Association.

“I suspect that at that time, increased deployments, extended tours of duty in Iraq, and diminished time at home had not yet had a major effect on Army units, as they do now,” said Raezer, in an interview. “From every measure I have, things are more difficult for families now than in 2004.”

Gibbs's study supports findings of an earlier study of child maltreatment rates in military families in Texas. That study found that while maltreatment rates were historically lower in military households than in comparable civilian families from 2000 to 2002, they began to rise as war approached and commenced, wrote E. Danielle Rentz, Ph.D., and colleagues (including Gibbs) in the May 15 American Journal of Epidemiology. Rentz was then in the Department of Epidemiology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and is now an epidemic intelligence service officer with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta.

Rentz and colleagues looked at files from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) for the state of Texas, which was chosen because it had a large military population and the most complete information on the military family status of child victims. They compared 1,399 children in military families with 146,583 in civilian families. Child maltreatment included physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect.

Rates of maltreatment in civilian families remained stable throughout the study period, January 2000 to June 2003, said Rentz. Military families had lower rates than among civilians until the last six months of 2002. However, as service members were deployed to war zones in late 2002 and early 2003, rates of maltreatment in military families rose above those of civilian families.

The child maltreatment rate in military families after October 2002 was double the rate before that time, while civilian rates remained the same.

Arguments can be made in both directions for risk and protective factors when comparing civilian and military populations. On the one hand, military families face stresses like repeated relocations, separations caused by deployments, and a dangerous work environment. On the other hand, troops must meet educational, psychological, and physical health standards upon enlistment. They receive housing, health care, and both formal and informal family psychosocial support. Drug and severe alcohol abuse is not tolerated.

The threshold for tolerating child maltreatment is probably lower in military settings, but those thresholds haven't changed, said Cozza, and he believes the rate is indeed going up.

“These studies indicate the need for more scientific understanding of the impact of deployment on families and children,” said Cozza.

Raezer agreed. “We're doing a good job capturing what's happening with deployed service members, but not as good a job with their families,” she said. “There should be more research because there's a lot we don't know.”

Better outreach, increased resources, and more effective services would help families left behind during a spouse's tour of duty, said Gibbs. The Army does have the Family Advocacy Program, family readiness support groups, and family assistance centers to help. The service has also instructed all primary care providers to ask patients about deployment in the family, screen for depression, and refer if needed, she said.

“The Army is doing more now to help than in 2002, but it's still not enough,” said Raezer. “Nobody's doing enough. We need ongoing research and ongoing support.”

However, further studies on this dataset depend on Congressional funding, which has not yet been authorized.

“Given the increased deployment tempo and casualties, I would really like to know what is happening,” said Gibbs.