There is little doubt that hot weather can adversely affect people's health. During periods of sizzling temperatures, there is a surge in the hospital admissions of patients with heat-related conditions and deaths due to various causes. Severely mentally ill patients are at an even greater danger of dying during brutal temperatures than the general population is, according to a report in the August 1998 Psychiatric Services, by Nigel Bark, M.D., of the Bronx Psychiatric Center in the Bronx, N.Y.

Now it looks as though heat may have an impact on suicides as well, a study published in the August British Journal of Psychiatry has found. It was headed by Lisa Page, M.D., a clinical lecturer and National Institutes of Health research fellow at the Institute of Psychiatry at King's College London.

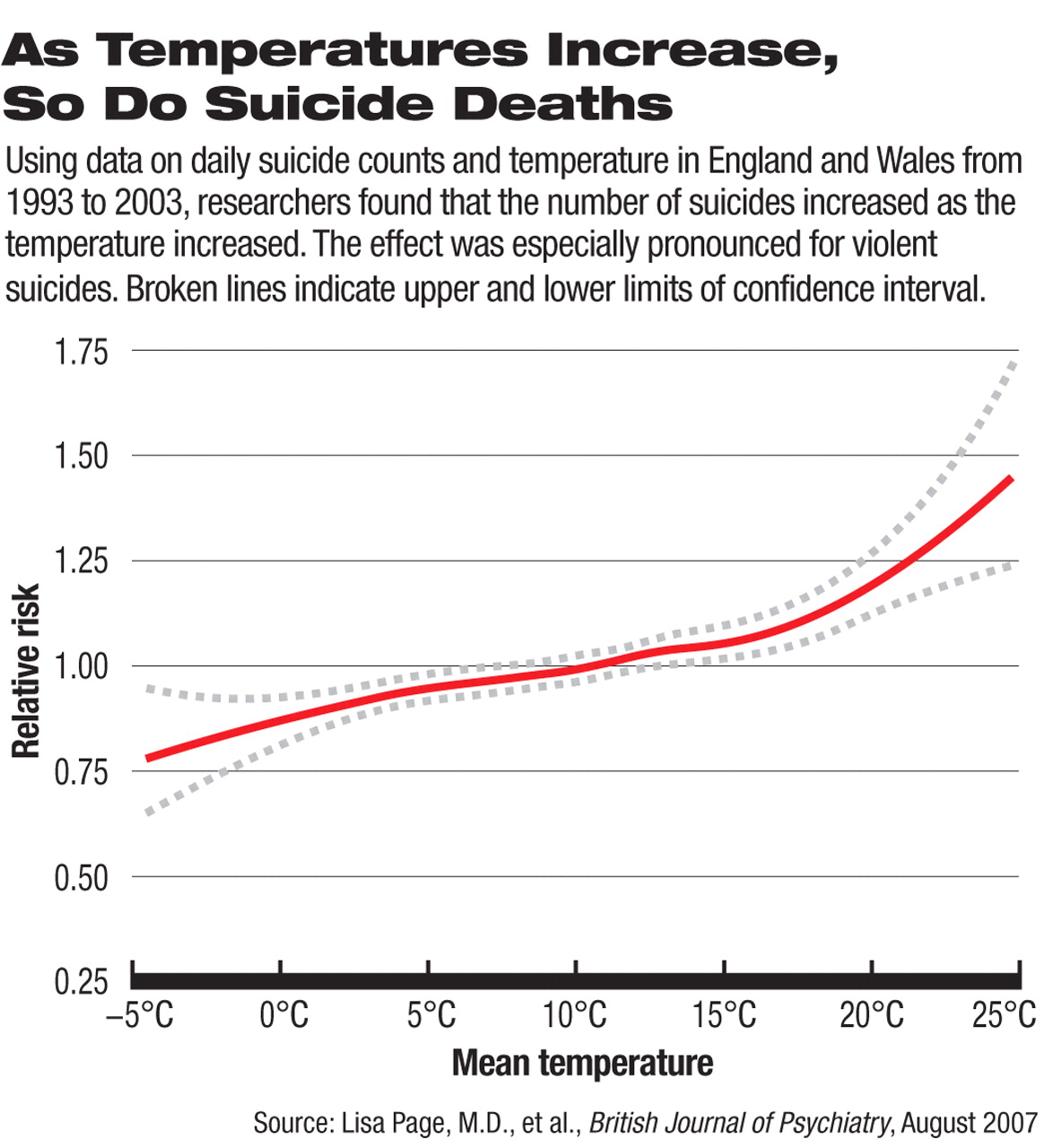

Page and her colleagues investigated whether there was any relationship from 1993 to 2003 between daily suicide counts in England and Wales and daily temperatures. They took various factors into account that might have skewed results, including year of death, month of death, day of the week, public holidays, and hours of daylight.

They found an association. Above 18 degrees Celsius (64 degrees Fahrenheit), there was strong evidence for a small but significant effect of increasing temperature on all suicides, but especially on violent ones. In fact, suicides increased by 42 percent during the July 29 to August 3, 1995, heat wave, compared with what was expected for that time of year. This 42 percent was well in excess of the 11 percent increase in all-cause mortality reported for the same period.

Concluded Page and her colleagues: “There is increased risk of suicide during hot weather.... This is the first time that death from suicide has been shown to be contributing to the known increase in all-cause mortality at higher temperatures.”

The ways in which high temperatures might contribute to suicides remain to be determined, though. The neurotransmitter serotonin might be implicated, Page speculated during an interview, since “serotonin levels are known to vary cyclically around the year, with low levels in the summer months. Also, postmortem studies have shown that people who commit suicide are more likely to have low levels of central serotonin.... However, I know of no evidence to support the idea that serotonin levels respond quickly to increases in temperature, which is what would have to be the case for this to be a realistic explanation for our findings.”

Nonetheless, Page and her colleagues believe that the putative impact of hot weather on suicidal behavior will become even greater as global warming continues.

“I am not sure that these results have huge implications for psychiatrists,” Page admitted. “The effect of temperature on suicide is small when considering any one individual patient and when contrasted with traditional (individual level) risk factors such as male gender, previous self-harm, or major mental illness.”

Nonetheless, she does believe that the results have public health implications and that countries' health-service plans for heat waves should perhaps address suicide prevention.

“Those with mental illness are highlighted as an at-risk group in England's heat-wave plan,” she said, “although this is because of their increased susceptibility to heat stroke rather than for suicide prevention.”

Interestingly, in charting the relationship between daily suicide counts and daily temperatures over the course of a decade, Page and her colleagues could not find any peak in suicides during the spring and summer months, as have a number of researchers in the past. One reason, she said, may be because“ temperature has a short-term, that is, near-immediate, effect on suicide that may well not be reflected if monthly patterns are inspected.”

Another possible explanation is that high temperatures do not play any role in the spring-summer suicide peak. A 2003 study found that the hours of bright sunlight a day, not temperature, explained the peak in suicides during Australia's spring and summer (Psychiatric News, June 20, 2003).

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the Wellcome Trust, and the European Commission Directorate-General for Health and Consumer Protection for the EuroHEAT project.