The number of suicides among children and adolescents rose dramatically at the same time that the number of prescriptions for antidepressant medications fell, following public health warnings from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) about a putative association between suicide and antidepressant use.

In addition, the same pattern of rising suicide and declining antidepressant prescriptions for children and teens was seen in the Netherlands.

These findings, which were reported in the September American Journal of Psychiatry (AJP), have APA leaders calling for the FDA to reconsider its advisory about antidepressant use, including a black-box warning the agency placed on antidepressants in 2004.

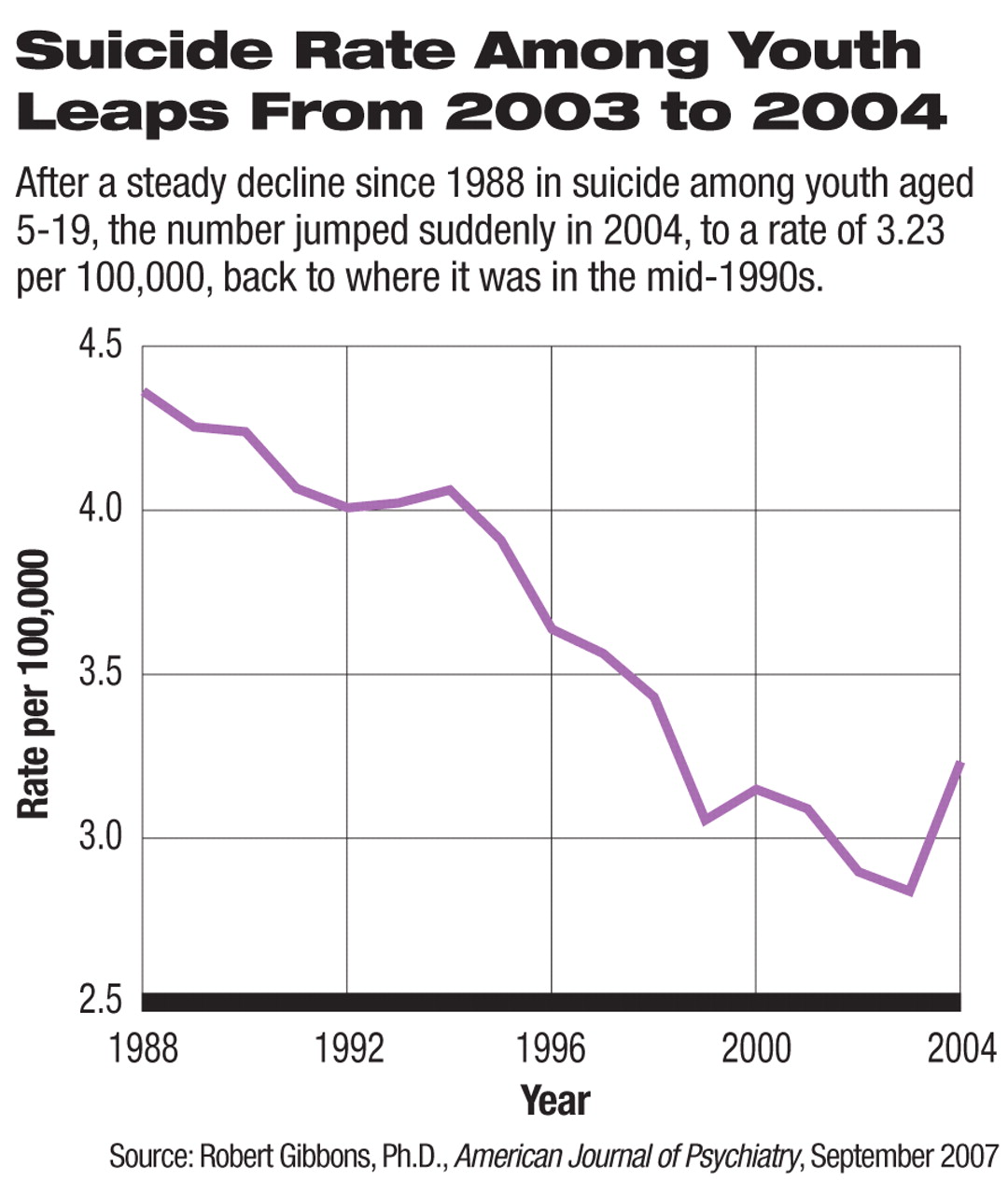

In the United States 1,737 suicides by children aged 5 to 19 were recorded in 2003; in October of that year the FDA issued its first public health advisory regarding several reports of children and teenagers taking antidepressants who attempted or committed suicide (see

Youth Suicides on Rise—Question Is Why?).

The following year, 1,985 suicides were recorded in the same age group, representing a 14 percent increase, the largest year-to-year change in suiciderates in this population since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began systematically collecting suicide data in 1979, according to the AJP report (Psychiatric News, March 2).

The FDA followed its initial health warning with another one in February 2004, and in October 2004 the administration ordered pharmaceutical companies to add a black-box warning to the labeling of all antidepressants used with pediatric patients regarding a possible increased risk of suicidality in pediatric patients taking antidepressants.

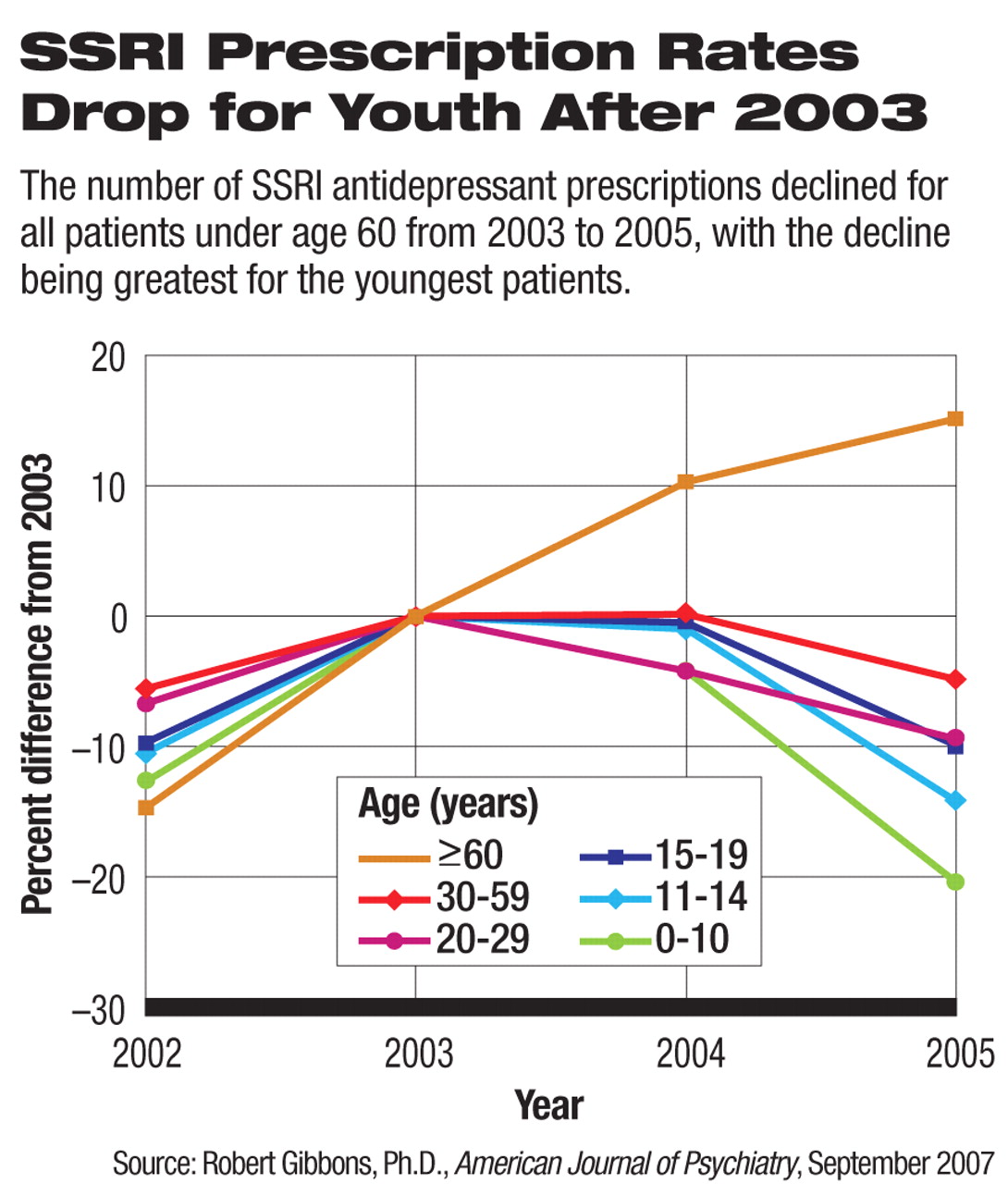

It was during this period of concern about antidepressant use and suicide—while youth suicides were rising—that prescriptions for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) decreased for all patients under age 60, with the decline being greatest for the youngest patients: from 2003 to 2005 prescriptions for children age 0-14 declined approximately 20 percent overall and 30 percent for new prescriptions, according to AJP.

Though much of the AJP report cited statistics specific to SSRIs, Gibbons and colleagues also looked at patterns of non-SSRI antidepressant prescribing and found the same decreases.

“Although some might expect that decreases in SSRI prescriptions would have led to increases in alternative antidepressant treatments, such as the newer nonserotonergic-specific antidepressants and tricyclic antidepressants, this does not appear to have been the case,” the authors wrote. “Similar decreases were seen in pediatric and young-adult prescription rates for both these alternative antidepressant types (approximately 20 percent in the 5–14 years age range and approximately 10 percent in the 15–19 years age range).”

Though there is no proof of a causal association between rising suicide rates and declining antidepressant use, the study authors believe the coincidence of the two phenomena is compelling.

“Our study represents an analysis of a frightening natural experiment,” Robert Gibbons, Ph.D., director of the Center for Health Statistics at the University of Illinois, told Psychiatric News.“ The results are not encouraging. More data are needed, and we are working with CDC to analyze data on suicide for 2005 to verify this phenomenon.

“But we have clearly shown that there has been a substantial decrease since the early public health advisory in 2003 and the black-box warning in 2004 in antidepressant prescriptions for children,” Gibbons said.“ During this same period, there has been a record increase between 2003 and 2004 in teen and child suicides.

“This is unprecedented. An increase of 14 percent is monumental. It is the largest change of any kind in these statistics since the CDC started monitoring youth suicide. And it is by far the largest increase in teen and child suicide since the introduction of antidepressant medication.”

Data on 2005 suicides among youth are expected to be released later this year, said Gibbons, a professor of biostatistics and professor of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

The data on suicides for the report in AJP were from the CDC's Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS).

Following publication of the AJP article, the CDC—in a weekly Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) issued in the second week of September—reported statistics from the same WISQARS database on trends in youth suicide for a different age group (10 to 24 years). That report found an 8 percent increase in suicide in that age group from 2003 to 2004 (see Youth Suicides on Rise—Question Is Why?).

The alarming confluence of increasing suicides and decreasing antidepressant prescriptions has leaders in child psychiatry calling for the FDA to reconsider the advisory and black-box warnings.

“It is definitely time for the FDA to revisit the black-box language in light of these findings,” said APA President Carolyn Robinowitz, M.D.“ The AJP report documents the considerable decline in treatment following the FDA's imposition of the black-box label, and the 14 percent increase in suicides in youngsters under 19 after more than a decade of declines.”

Robinowitz emphasized that, in contrast, there were no suicides in the studies that had originally prompted the FDA's black-box decision. And she drew attention to the fact that the AJP report and CDC figures were issued in time for National Suicide Prevention Week, September 9 to 15.

“Education is so important in raising awareness about suicide prevention and treatment,” she said.

David Mrazek, M.D., chair of APA's Council on Children, Adolescents, and Their Families, echoed Robinowitz's comment about no suicide deaths in the studies leading up to the FDA advisory warnings. “This is the really poignant part,” he said, “that on the basis of an analysis in which there were no suicides, the FDA made a decision that now seems to be very probably linked to actual suicides.

“From a public health as well as a clinical perspective, I hope that the FDA will promptly convene a group to examine these data and consider the consequences of this warning.”

Mrazek is chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The last time that antidepressant labeling and medication guides were updated was this past summer in response to recommendations made by the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee at the end of 2006. The committee called for language to reflect the risk of suicide associated with untreated depression in children and young adults up to age 24 and the danger associated with untreated depression. The updated information now includes the statement,“ Depression and certain other psychiatric disorders are themselves associated with increases in the risk of suicide.”

Responding to an information request from Psychiatric News, an FDA press officer said the administration was not considering a change in the black-box warning.

“At this time nothing indicates a need for change in the black-box warning on these drugs, which urges attention to patients starting treatment—still good advice—and does not suggest avoiding the drugs,” the press officer stated. “We have not at all tried to discourage use of antidepressant drugs in depressed children, just remind people of the care needed.

“We are anticipating the new adolescent suicide data (2004 to 2005) that should become available later this year. We expect that other data will also have accumulated at that point—newer suicide data from other countries, other epidemiologic data pertinent to suicidality, newer use data for antidepressants, and possibly additional efficacy data. It will be important to assess all available data together.”

Several lines of evidence appear to support the association between a rise in youth suicide and the decline in antidepressant prescriptions. Among these is the fact that the same pattern observed among American youth by Gibbons and colleagues in the AJP report was also found among youth in the Netherlands.

There, where suicide data are available through 2005, the researchers found that the SSRI prescription rate declined by 22 percent for patients under age 20, while the suicide rate increased by 49 percent between 2003 and 2005.

Further supporting the association is the finding that suicides for people aged 60 and over in the United States reached a record low in 2004. Meanwhile, SSRI prescriptions increased between 2003 and 2005 by 15 percent for this age group, the only age group to experience an increase in being prescribed an antidepressant after 2003 and the time of FDA's public health warnings.

All of these indicators point to an ominous conclusion.

“While these data do not provide a causal link, they are extremely suggestive,” Gibbons said. “These are ecological data, but I haven't heard any other hypothesis [that explains the increase in suicides] that is credible.”

In the September AJP report, annual U.S. antidepressant prescription rate data for 2003–05 by ZIP code were drawn from a random sample of 20,000 pharmacies from the 36,000 pharmacies in the database of IMS Health in Plymouth Meeting, Pa., which represents over half of all retail pharmacies in the continental United States.

Though the database does not include hospital prescriptions, the investigators used data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Evaluation Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Evaluation Survey to compute the ratio of hospital to nonhospital prescriptions for SSRIs by year; they found that the IMS Health data account for nearly 90 percent of SSRI prescriptions in the United States.

Data on national suicide rates in the Netherlands from 1998 to 2005 for children up to age 15 and teenagers aged 15 to 19 came from the Central Bureau of Statistics. Prescription data in the Netherlands were obtained from the PHARMO database at<www.pharmo.nl>. The database consists of a representative sample of more than 200 pharmacies in more than 50 regions representative of the Netherlands.

The study was supported by NIMH. Prescription data were obtained from IMS Health with the assistance of a grant-in-aid from Pfizer. Pfizer was not involved in the research and did not review the results or the manuscript prior to submission.