Patterns of religious affiliation among psychiatrists differ from those of other physicians, and these contrasting religious beliefs may determine to whom patients are referred for mental health care, according a study in the September Psychiatric Services.

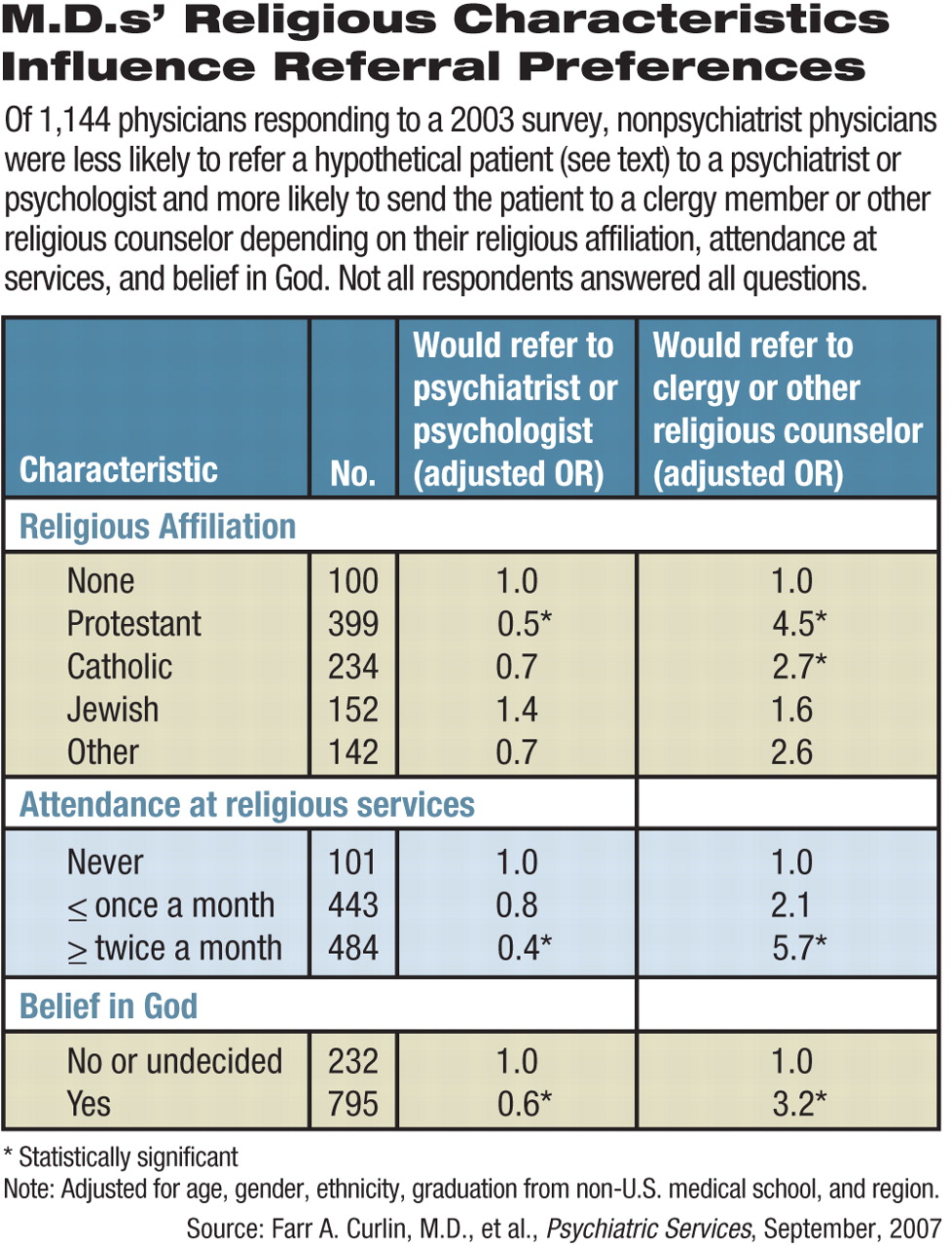

Researchers from the University of Chicago and Duke University mailed a survey in 2003 to a sample of 2,000 U.S. physicians from the AMA Physician Masterfile and received replies from 1,144 (63 percent), including 100 psychiatrists. The survey asked about their religious and spiritual characteristics and also asked the nonpsychiatrist physicians to whom they would refer a hypothetical patient with ambiguous psychiatric symptoms.

“Psychiatrists were less likely [than other physicians] to attend religious services frequently, believe in God or the afterlife, or cope by looking to God,” reported Farr Curlin, M.D., an assistant professor of general internal medicine at the Pritzker School of Medicine at the University of Chicago, and colleagues. “In addition, psychiatrists were less likely to classify themselves as religious and more likely to classify themselves as spiritual but not religious.”

Tension between psychiatrists and religious believers is not new. It may have been exacerbated by Sigmund Freud, who had unpleasant things to say about religion in his famous essay “Future of an Illusion.” However, the rift is probably not so unbridgeable today as it might once have been, Jeffrey Boyd, M.Div., M.D., told Psychiatric News.

Boyd has seen both sides of this divide. He went to Harvard Divinity School and was ordained as an Episcopal priest before entering medical school at Case Western Reserve University. After residency at Yale in the late 1970s, he worked at the National Institute of Mental Health in psychiatric epidemiology. Since 1986 he has practiced at Waterbury Hospital in Connecticut, where he is now chair of behavioral health.

“In my experience, people who are more religious see the mental health field in general as hostile, so representation of psychiatrists among those people is lower,” speculated Boyd, who was not involved with Curlin's study.

The researchers asked all the doctors about organizational or participatory religiosity—how often they attended services and whether they believed in God or an afterlife. They inquired about intrinsic religiosity—“the extent to which an individual embraces his or her religion as the 'master motive' that guides or gives meaning to his or her life.” They also asked about “spirituality,” a term that they concede is ambiguous but may cover both formal religion and feelings of a connection with an entity greater than oneself that gives life meaning.

Responding psychiatrists, they found, were less likely to be Protestant or Catholic and more likely to be Jewish or to declare no religion than were other physician respondents. According to the survey report, 13 percent of the U.S. population claim no religious affiliation, compared with 10 percent of the responding physicians and 17 percent of psychiatrists. Protestants make up 55 percent of the U.S. population, but accounted for only 39 percent of the respondents and just 27 percent of the psychiatrists. Catholics make up 27 percent of the population, but made up 22 percent of responding physicians and 10 percent of the psychiatrists, while Jews, who account for less than 2 percent of the population, made up 14 percent of physicians in the survey and 29 percent of the psychiatrists. Muslim and Hindu psychiatrists closely matched the proportion of their other medical colleagues, but absolute numbers were quite small.

In the hypothetical case, the patient was described as a man mourning intensely two months after his wife's death.

“The religious characteristics of physicians determine to some extent whether their patients receive evaluations from psychiatrists,” wrote the researchers. A religious nonpsychiatrist would be more likely to refer the patient to a clergy member or other pastoral counselor rather than to a psychiatrist or psychologist.

Protestant and Catholic physicians, for example, were less likely than those with no religious affiliation to refer to psychiatrists or psychologists, and more likely to refer patients to a clergy member or other religious counselor. Jewish physicians were almost equally divided on the question.

“A lot could be explained by unfamiliarity, not antipathy,” said John Raymond Peteet, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and chair of APA's Corresponding Committee on Religion, Spirituality, and Psychiatry. “Conservative Muslims, Jews, and Christians all want someone who understands them, and if their clergyperson vets a psychiatrist, they will trust their values.”

However, there is no wall separating believing nonpsychiatrist physicians from their psychiatric colleagues, said Peteet in an interview. “Most religious internists have psychiatrists they know and trust, regardless of their religious orientation, but I have heard of cases of not referring to secular specialists so as not to undermine the world view of patients, as in cases that might lead to divorce.”

In fact, the hypothetical case may be a little too simplistic to permit drawing any valid conclusions, said Boyd. Perhaps differing views on the nature of religion may underlie the aversion to psychiatry among fundamentalist Protestants and devout Catholics, he said, citing Erich Fromm's distinction between “humanistic” and “authoritarian” religious belief systems. For instance, the Talmudic tradition in Judaism of inquiry and argument—a very “psychological process,” said Boyd—contrasts with a desire among Christian believers to find the authority for the answer.

Why religious physicians would choose not to refer to a psychiatrist is open to speculation, said Curlin. Perhaps memories of Freud's antireligious arguments or the “liberal political views of many influential psychoanalysts of the 1950s and 1960s” still have their effect. In contrast, Curlin also suggested that current emphasis on biological psychiatry may equally alienate religious doctors.

Patients for whom religion is an important part of their lives have often learned not to talk about religion to therapists for fear of being thought poorly of, said Boyd. About seven years ago, he began wearing a small cross on his collar as an outward indication of his faith, much as his observant Jewish colleagues wear yarmulkes. He has found almost no negative reactions to that move but has seen an increased willingness for religious Christians to be more open when they see a sign of his religious background.

By whatever means, the worlds of religion and psychiatry may be slowly moving to close the gap as both sides learn more about the other.

“In the last three decades, some form of counseling training has been adopted in almost all seminaries in the Christian world, even in the most conservative,” said Boyd. “The pro-mental health rather than the anti-mental health point of view has come out the winner.”

Curlin and colleagues suggested that psychiatric training include more cultural sensitivity to religious beliefs to help overcome any distrust. Earlier studies found that psychiatry residents are less irreligious today, so perhaps any current differences can be expected to moderate over time.

Another psychiatrist has suggested that clergy and psychiatrists can learn from each other and that religious and biomedical forms of healing are not incompatible.

“It is not just that religious professionals need to be educated about mental illness, but also it is vital that psychiatrists understand religious experience,” wrote Simon Dein, M.B.B.S., M.R.C.Psych., Ph.D., a senior lecturer in psychiatry in the Division of Medicine at Royal Free and University College Medical School, University College London, in a letter to the British Journal of Psychiatry. Dein has studied the intersection of mental health and religiosity among both Pentecostal Christians and Orthodox Jews. “Mental health professionals need to be knowledgeable about the circumstances in which referrals to religious professionals are appropriate.”

“Will there be a slow convergence of the mental health world and the Christian religious world in my lifetime?” asked Boyd. “I think it's moving in that direction.”