It took 20 years, but New Yorkers finally gained a mental health parity law that met many long-sought goals.

The measure, said supporters, will save many families from the anguish of surrendering custody of their children to the state because they are unable to afford care for the children's serious mental health problems, despite having health insurance coverage. The law is also expected to save millions of dollars annually in lost productivity that stems from workers with untreated mental illness.

“This is something New York state psychiatrists have been pushing to achieve for years,” said Deborah Cross, M.D., president of the New York State Psychiatric Association (NYSPA) and chair of APA's Committee on Public Affairs.

She credited the eventual passage of the law to a “multiple-party effort” by a coalition of mental health consumers, families, and psychiatrists that kept pressure on legislators for many years.

The law, which took effect January 1, requires health insurers to provide comparable insurance coverage for “biologically based” mental illnesses as policies provide for other medical care.

The law requires health insurance plans to provide at least 30 days of inpatient care annually and at least 20 days of treatment with a psychiatrist or psychologist in a state-certified facility, a facility operated by the State Office of Mental Health (OMH), or a group or academic practice.

The cost of premiums and deductibles must remain consistent with such fees for other types of medical care.

The law requires health insurance coverage for businesses with at least 50 employees to cover treatment for schizophrenia/psychotic disorders, major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorders, bulimia, anorexia, serious cases of attention-deficit disorders in children, disruptive disorders, and pervasive developmental disorders.

Another component of the law mandates coverage for children with serious suicidal symptoms or other life-threatening self-destructive behaviors, significant psychotic symptoms, behavior caused by emotional disturbances that place the child at risk of causing personal injury or significant property damage, or behavior caused by emotional disturbances that place the child at substantial risk of removal from the household.

Businesses with fewer than 50 employees must make the parity coverage available for workers to purchase upon request.

The law seeks to offset additional costs to these workers by directing the superintendent of the State Insurance Department to develop a program of state funding to cover the additional premium costs for workers at smaller companies.

New York psychiatrists maintained the law will significantly reduce the problems that people with mental illness have affording the care they need.

“I think it's reasonable to assume that most individuals who needed treatment for mental health disorders could not afford it before this because their insurers didn't cover it, and they couldn't afford the out-of-pocket cost,” Seth Stein, J.D., executive director of NYSPA, told Psychiatric News.

Fifty-three percent of New York's 19 million residents have employer-sponsored insurance, and 4 percent are self-insured, according to federal government data compiled in November 2006 by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

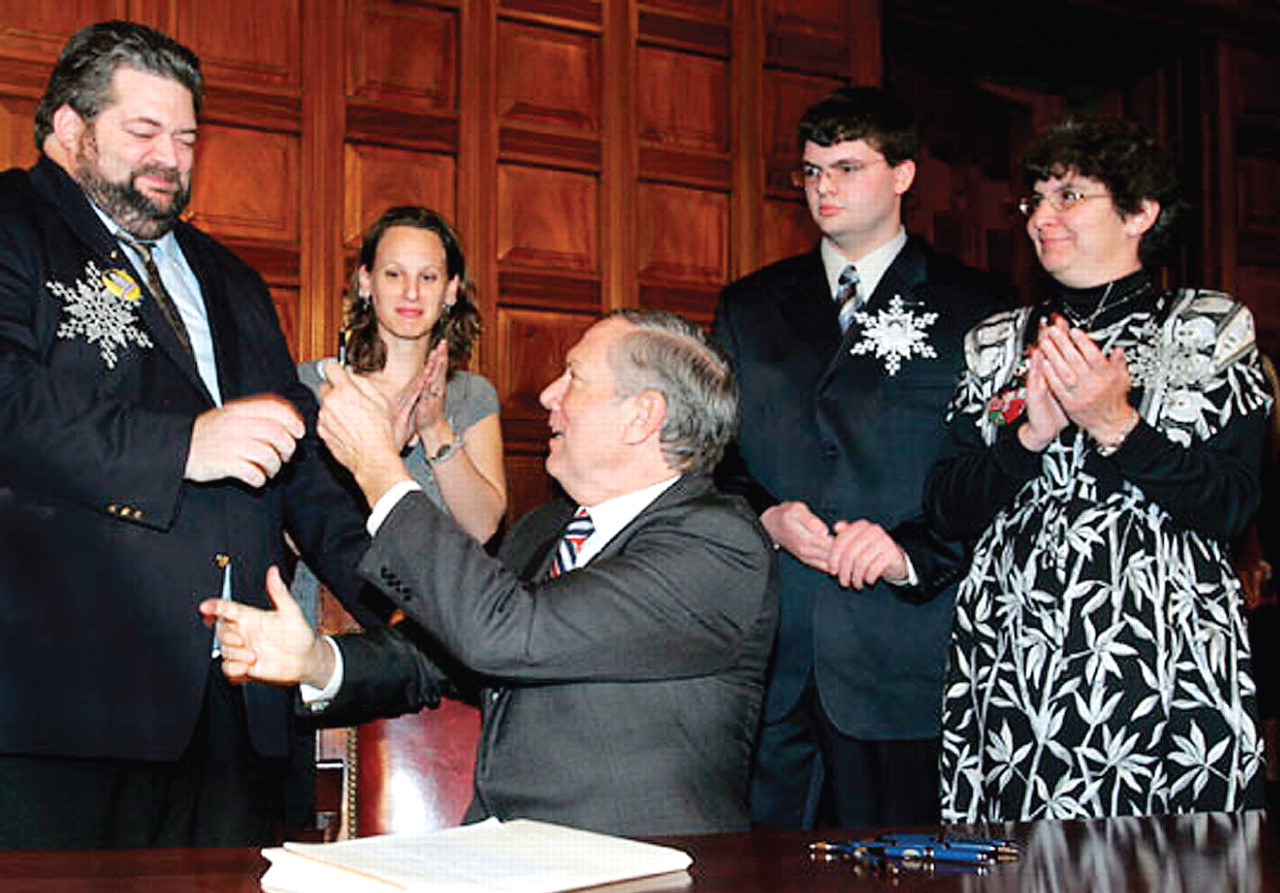

The new parity measure, known as Timothy's Law, is named after a New York boy whose parents had given up custody to the state because they were unable to afford treatment for his depression. The boy committed suicide at age 12.

Costs Remain Unknown

Although the New York State Assembly had passed a full parity measure in several consecutive years, opponents held up its progress in the state Senate due to concerns that it would impose huge costs on businesses, insurers, and policyholders. One of the main opponents, the Business Council of New York, dropped its long-standing opposition to the bill late in the last legislative session after a compromise amendment was added to remove coverage mandates for posttraumatic stress disorder and drug and alcohol addiction treatment. Other business groups continued to fight the measure.

The cost of the final measure is not yet known but estimates varied from a few million dollars to $60 million, or an increase in insurance premiums of between 3 percent and 10 percent.

Supporters of the new law noted that multiple studies, including one on a parity mandate for federal workers (Psychiatric News, September 15, 2005), have found that parity laws do not have a high cost. That study, sponsored by the Department of Health and Human Services, found that the federal parity mandate, which was implemented in 2001, did not significantly increase the use of mental health services under the Federal Employee Health Benefits program, but did lead to significant reductions in out-of-pocket spending for many government workers and retirees.

The study did not assess whether any increased costs were passed on to other subscribers, but the lead author estimated any increased premium costs were likely less than .5 percent.

More Legislation Needed

Although parity supporters consider the New York measure a huge success, many remain adamant that future legislation add a coverage requirement for posttraumatic stress disorder and drug and alcohol addiction treatment.

“We view this law as a substantial beachhead, and now we're going to push for true parity,” Stein said.

Supporters may have a chance to expand the law when it comes up for renewal by the legislature in 2009. If the legislature does not renew it, the law will expire three years after enactment. The law also requires state health officials to study its costs and financial and health impacts to provide the facts upon which legislators can base their future parity actions.

The text of the parity law (S 8482) is posted at<www.nyspsych.org/public/components/societytools/admin/viewNewnews.asp>.▪