Administration opposition and Congress's inability to pass the 2007 federal budget will slow implementation of the most extensive study about environmental influences on the health and development of children in the United States, said the project's director.

Recruitment for a prospective study of 100,000 children from conception to age 21 was scheduled to begin this year at seven pilot sites. A subsequent phase would expand the program to an additional 98 sites across the country. However, the continuing resolutions designed to keep the government afloat until formal budget passage means that only planning of the study's protocol can go on for the moment, said Peter Scheidt, M.D., M.P.H., director of the National Children's Study (NCS), a part of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. “Congress would need to appropriate more funds to get the study teams into the field to collect data.”

The NCS had received $10 million to $12 million a year over the previous five years for planning and had hoped to get $69 million to begin work at the seven pilot sites. The total estimated cost over 25 years is $2.7 billion, a figure that would be offset by savings from projected expenditures on the chronic diseases covered by the project, said project leaders.

Even the current situation represents some progress, Scheidt told Psychiatric News. The Bush administration's 2007 budget proposed eliminating the project, possibly a victim of the flat National Institutes of Health (NIH) budget.

“Budgetary priorities” led to the decision of not completing the pilot program, NIH director Elias Zerhouni, M.D., testified to senators last May, leaving the door ajar to completing the program in easier fiscal times. Nevertheless, House and Senate committee reports supported the study and implied that funds would be restored—when a budget was passed.

The NCS will examine environmental and individual risk factors for asthma, birth defects, dyslexia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, schizophrenia, obesity, and adverse birth outcomes.

The project is funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with the cooperation of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Longitudinal epidemiological research— like the Framingham Heart Study, the Nurses' Health Study, and the California Child Health and Development Study—has provided valuable information on risk factors and causes of disease. However, the NCS will go a step further.

“Other countries have tracked children from birth or from prenatal observations,” psychiatrist Ezra Susser, M.D., the Gelman professor and chair of epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University and a professor of psychiatry at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, told Psychiatric News. “But this study will have greater scale and depth since it will start from conception.”

The NCS reflects a view of disease etiology that has expanded since World War II to include not only infectious illnesses but the chronic diseases that now affect even larger numbers of Americans. Known or suspected environmental influences may cause acute illness, but they also have subtle effects that can be discerned through only long-term epidemiology studies in large populations.

Children are at special risk from the 2,800 plastics, pesticides, fuels, building materials, hormones, and other synthetic chemicals produced in quantities of over 1 million tons a year each.

Recent studies have detected such chemicals in the bodies of most Americans. Children are at higher risk than adults for several reasons. They will live longer and so be exposed longer to environmental agents; the developmental process may make them more vulnerable than adults; pound for pound, they take in more air, water, and food and so are exposed more; and metabolic and excretory pathways are immature, at least shortly after birth, and so they are less able to rid their bodies of potential toxins, according to an article on the NCS in the November 2006 Pediatrics.

The NCS planners hope that several questions involving psychiatry will be answered over the trial's 25-year span. The study will look at how psychosocial stressors cause neurobehavioral outcomes and whether those processes involve altered gene expression.

“We plan to gather data on cognitive and emotional development, conduct disorders, developmental disorders—in fact, virtually all disorders with a frequency greater than 2 in 1,000,” said Scheidt.

“Only a large-enough birth cohort can gives us the behavioral, genetic, and geneexpression data we need to make progress in understanding autism,” added Susser. “We also need more in-depth data on the origins of schizophrenia.”

Susser is part of a team at Columbia that has been using data from the California Child Health and Development Study to look for prenatal environmental influences on the etiology of schizophrenia.

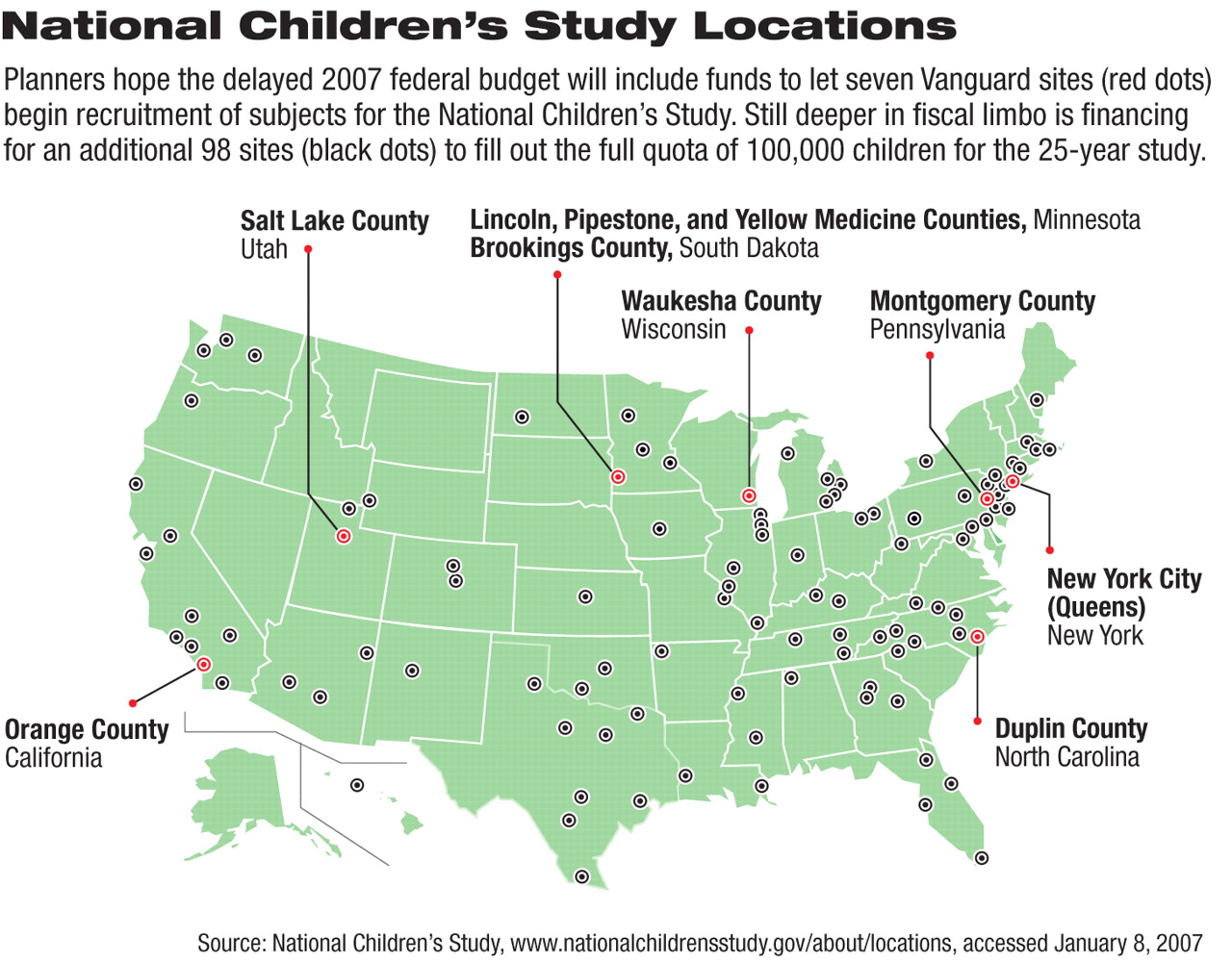

If Congress allocates funds, seven Vanguard dites will open in California, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Utah, Wisconsin, New York City, and four counties straddling the border of South Dakota and Minnesota. Teams at those centers will enroll women of childbearing age to yield 250 newborns a year for five years, beginning in 2008. Investigators will visit homes before conception; three times during pregnancy; at 1, 6, 12, and 18 months; and at 3, 5, 7, 9, 12, 16, and 20 years to collect biological and psychosocial data. Additional funding is needed to expand to an additional 98 sites in 39 states.