Fetuses that experience a favorable sojourn in the womb may be better protected against anxiety and depression later in life, a study in press with Biological Psychiatry suggests.

The study was conducted by Ian Colman, Ph.D., of the University of Albert School of Public Health in Edmonton, Canada, along with colleagues at the University of Cambridge and University College London in England.

A wealth of data links schizophrenia to unfavorable conditions in the womb, Colman and his colleagues noted. For example, low birth weight, as a proxy for prenatal damage, as well as more direct insults such as obstetric complications, have been shown to increase the likelihood of schizophrenia. So the investigators wanted to find out whether two indicators of an adverse womb environment—low birth weight and slow motor development after birth—might be linked with an increased risk of anxiety and depression later in life.

Some 4,600 persons born in the United Kingdom in 1946 and representative of all native-born adults currently residing there served as subjects. These individuals were evaluated not only for birth weight, early motor development, and early speech development, but were also assessed five times between the ages of 13 and 53 for symptoms of anxiety and depression.

The anxiety and depression evaluations at ages 13 and 15 were made by the subjects' teachers. The teachers rated the subjects as more than, the same as, or less than classmates on the following 11 attitudes or behaviors reflecting anxiety, depression, and internalizing emotions and behaviors: timid child, rather frightened of rough games, extremely fearful, always tired and washed out, usually gloomy and sad, avoids attention, very anxious, unable to make friends, diffident about competing, frequently daydreams in class, and unduly miserable or worried in response to criticism.

The anxiety and depression evaluation at age 36 was made by trained research nurses using a short version of the Present State Examination, a clinically validated interview, to evaluate the frequency and severity of neurotic and affective symptoms during the preceding month.

At age 43, the subjects used the Psychiatric Symptom Frequency Scale, a self-administered yardstick, to rate themselves on the frequency and intensity of common symptoms of anxiety and depression during the preceding year.

Then at age 53, they completed the 28-item General Health Questionnaire, which focuses on the experience and impact of anxiety and depression symptoms during the previous month.

Six Patterns Identified

Colman and his colleagues then grouped the subjects based on anxiety and depression results into six longitudinal patterns. The largest group—45 percent of the sample—had few or no symptoms. The second group—34 percent—had repeated minor or moderate symptoms that were generally below the threshold for mental illness. The third group—11 percent—had few symptoms in adolescence, but had minor or moderate symptoms in adulthood. The fourth group—6 percent—had symptoms in adolescence but was mentally well in adulthood. The fifth group—3 percent—had few symptoms in adolescence, but had severe symptoms in adulthood. Finally, the sixth and smallest group — 2 percent—had enduring high scores indicating persistent or repeated severe symptoms as teens and adults.

The researchers then looked for differences among the groups on birth weight, early motor development, or early speech development, taking factors that might skew results, such as gender, social circumstances in childhood, and stressful life events in childhood, into consideration.

Average Birth Weights Varied

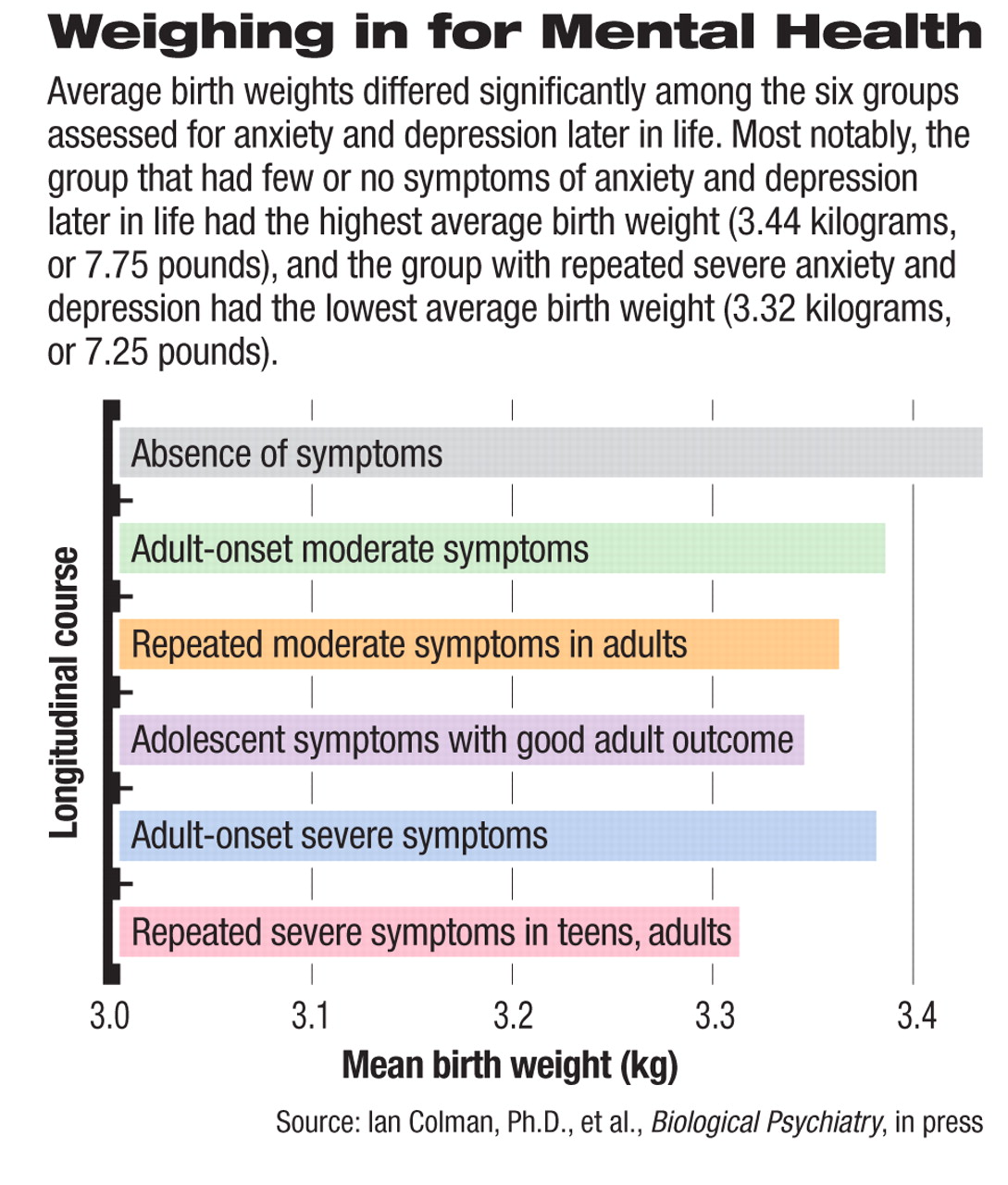

Average birth weights differed significantly among the six groups. Most notably, the group with few or no anxiety and depressive symptoms throughout the 40-year study period had the highest average birth weight (3.44 kilograms, or 7.75 pounds), whereas the group that had repeated severe anxiety and depressive symptoms had the lowest average birth weight (3.32 kilograms or 7.25 pounds).

Furthermore, early motor development differed significantly among the groups. Those with few or no anxiety and depressive symptoms were, on average, the first to stand and walk—they started walking, on average, at 13.4 months—while those with repeated severe symptoms were the last to stand and walk—they started walking, on average, at 14.4 months.

The six groups did not differ significantly on the age at which they began speaking.

Thus, low birth weight and slow motor development may be harbingers of later susceptibility to anxiety and depression, while robust birth weight and rapid motor development may signal some protection against anxiety and depression.

But only to a point, it seems. Although the researchers found that a birth weight up to 4.5 kilograms (10 pounds) was associated with less anxiety and depression later in life, they also found that beyond that birth weight, the relationship reversed—very large babies were in fact more likely to have depression and anxiety later.

How birth weight and early motor development might influence later susceptibility to anxiety and depression is not known. But Colman and his team suspect that a less-than-favorable womb environment might alter a fetus's neurodevelopment and stress response, and these alterations in turn might set it up for “poor mental health across the life course.”

The study was funded by the Institute for Social Studies in Medical Care, U.K. Medical Research Council, Stanley Medical Research Institute, Leverhulme Foundation, Isaac Newton Trust, and U.K. Department of Health.

An abstract of “A Longitudinal Typology of Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Over the Life Course” is posted at<www.journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/bps/article/PIIS0006322307004362>.▪