A substantial number of patients with depression are diagnosed and treated by primary care providers in community settings. A recent study found that patients have better outcomes when these physicians closely follow treatment guidelines. The study—published in the September Annals of Internal Medicine—also found that, although the majority of primary care physicians did well in following recommendations for screening and treatment initiation, they tended to miss the mark in assessing comorbidities and suicide risk and making therapeutic adjustments or referrals to psychiatrists or mental health professionals when patients did not respond well to treatment.

Kimberly Hepner, Ph.D., an associate behavioral scientist at the RAND Corp., and colleagues analyzed surveys of more than 1,000 patients with depression who were treated in the primary care setting and measured the quality of care against Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) guidelines. The data were collected during a Quality Improvement for Depression project from 1996 to 1998, in which 45 primary care practices within four health care organizations (including a family practice network, Kaiser Permanente, Veterans Affairs, and a network-model managed care organization) in 13 states were involved in collaborative quality-improvement activities. In the project, researchers identified patients at these sites who met criteria for depression and recorded details about the care the patients received through follow-up telephone interviews for the next two years.

This current study, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, AHRQ, the MacArthur Foundation, and Department of Veterans Affairs, analyzed the care activities, ranging from initial diagnosis to follow-up treatment, provided by the physicians over two years from the survey and patient-outcome data.

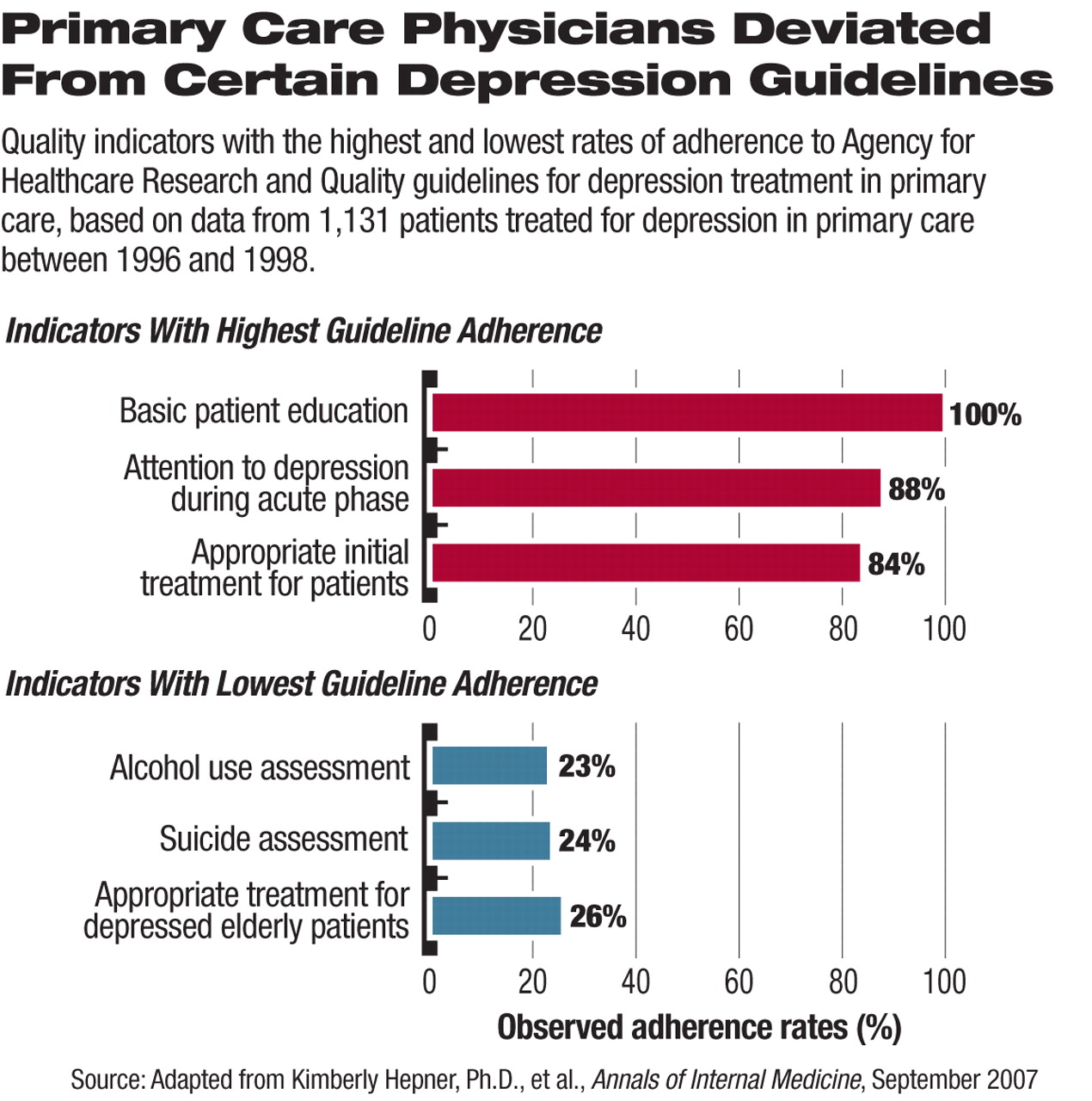

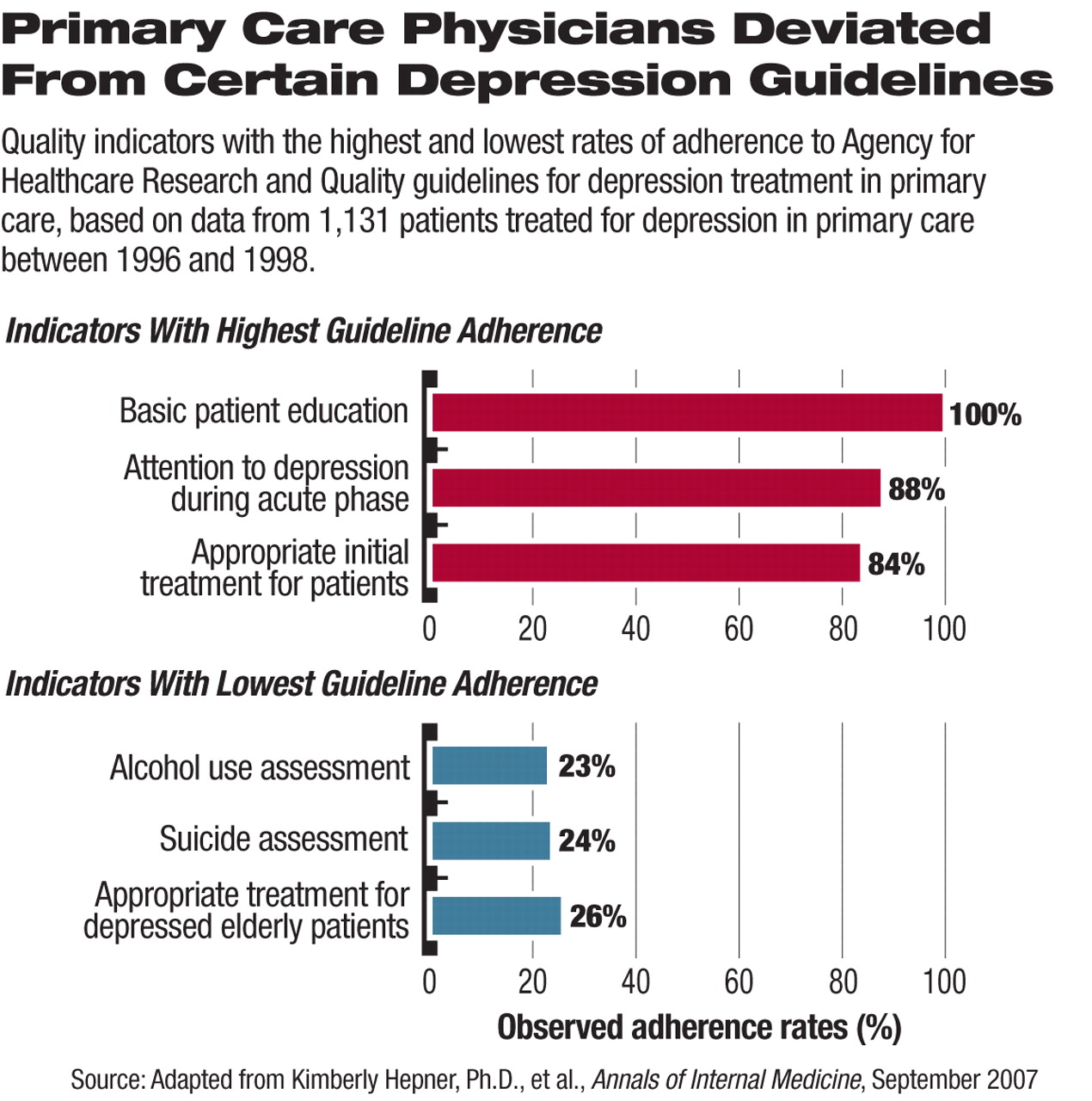

Because of a lack of quantitative instruments for measuring quality of depression care, the authors developed a set of 20 quality indicators based on the AHRQ depression care guidelines and validated this index. After comparing patient-care survey responses with the quality indicators, they found that the primary care physicians followed AHRQ guidelines the most closely in basic patient education, attention to depression during the acute phase, and providing appropriate initial treatment for individual patient complaints (all above 80 percent, see

chart); the least-followed indicators were alcohol-use assessment, suicide assessment, appropriate treatment for elderly patients, and treatment for suicidal ideation in patients not already treated by mental health providers (all below 30 percent).

“We conducted this study to provide a conceptual model for future research in quality of depression care,” said Lisa Rubenstein, M.D., coauthor of the study and director of the Veterans' Administration Greater Los Angeles/University of California at Los Angeles/RAND Center for the Study of Healthcare Provider Behavior, in an interview with Psychiatric News.“ Our study is the first to measure the broad range of aspects in depression care, while controlling for case mix. We wanted to encourage primary care practitioners to adhere to guidelines.”

The study results supported the clinical effectiveness of adhering to the AHRQ guidelines, with the findings showing that patients tended to have better outcomes when their primary care providers stuck to the guidelines. The findings appeared to confirm the effectiveness of evidence-based, expert-synthesized treatment guidelines.

“Primary care physicians talk to their patients about depression and follow up in the early phase [after diagnosis], but many are not able to perform intensive assessments of patients' comorbidities and treatment adjustments if the patient does not respond,” said Rubenstein on the barriers to better adherence to guidelines. “A full depression assessment takes 20 to 40 minutes, which can't be done in a 15-minute office visit or with lab tests.” She suggested practical approaches, such as training nurses and other personnel to perform evaluations, as a way to improve the quality of depression treatment in primary care settings.

An abstract of “The Effect of Adherence to Practice Guidelines on Depression Outcomes” is posted at<www.annals.org/cgi/content/abstract/147/5/320>.▪