Physical health tends to be better when people are young, but could the opposite be true for mental health?

Barring the onset of dementia or a terminal illness, the answer is often yes, a building body of provocative evidence suggests.

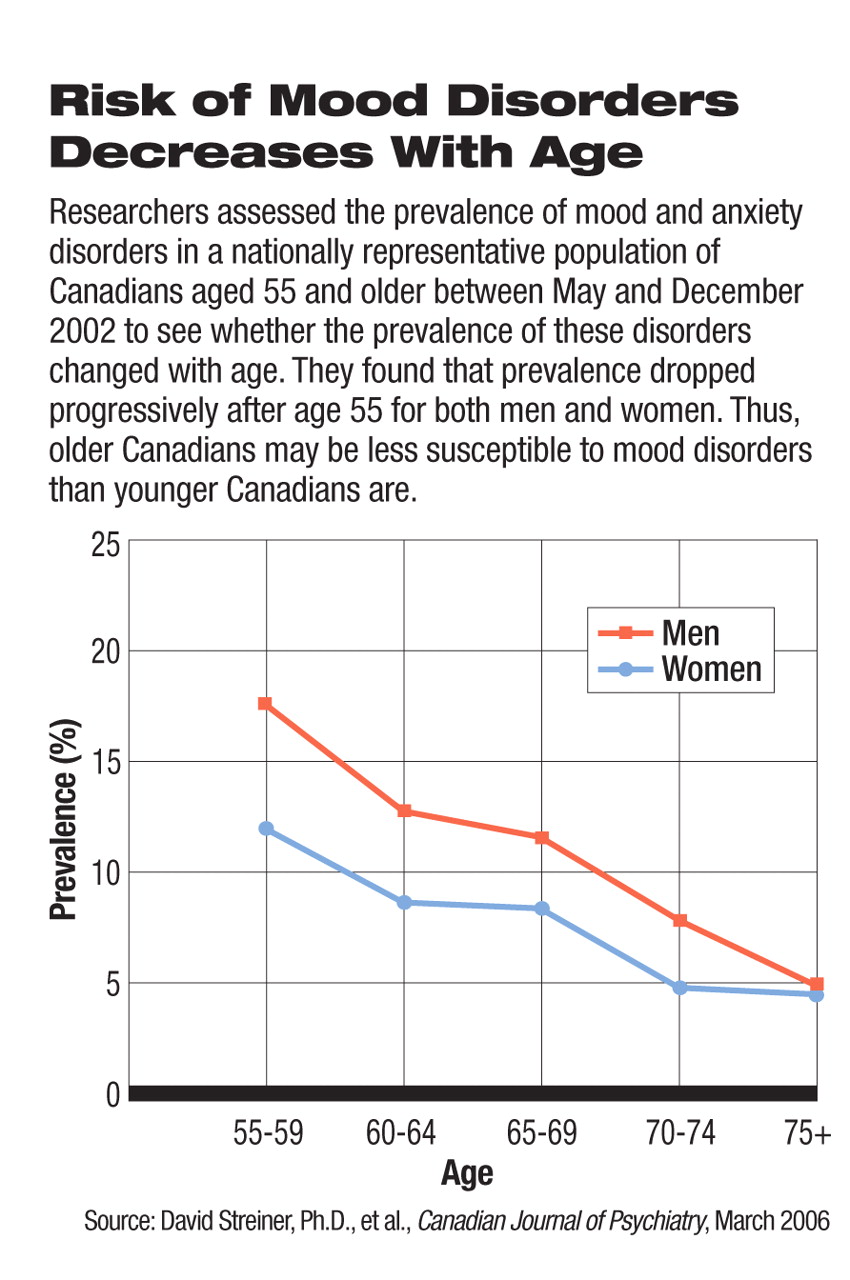

Take, for example, a study reported in the March 2006 Canadian Journal of Psychiatry by David Streiner, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto, and colleagues. They assessed the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in a nationally representative population of Canadians aged 55 and older to see if the prevalence of these disorders changed with age. They found that there was in fact a linear decrease for these disorders after age 55. This was true for men and women and for people born in Canada and those who immigrated to Canada after age 18.

Image (old_man) is missing or otherwise invalid.

Or take a study headed by George Vaillant, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Harvard University and co-director of the Study of Adult Development there. He and his colleagues followed a cohort of 151 innercity men from adolescence until an average age of 75. The men came from socially disadvantaged families, had dropped out of school, and had a low IQ. Nonetheless, a surprisingly large number enjoyed retirement in their later years. And as Vaillant and his group concluded in a report in the April 2006 American Journal of Psychiatry: “The very risk factors associated with bleak young adulthood, and the very risk factors associated with bleak midlife adjustment, appeared to exert relatively little effect on whether the men, followed since 1940, currently enjoyed retirement.... It appeared as if retirement created—for these men at least—a new age and a third chance at a contented life.”

Research conducted by Dilip Jeste, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and colleagues on 205 older people living in San Diego County also bolsters the case that mental health tends to improve with age. The researchers asked the seniors, who ranged in age from 60 to 102 and who had common physical illnesses that often afflict seniors, to rate themselves on a scale of 1 to 10 indicating how well they believed they had aged. A rating of 1 was the worst a subject could give himself or herself, and 10 was the best. The researchers expected most of the subjects to rate themselves with a 3 or 4, but it turned out that the average score was 8.4, the researchers reported in the January 2006 American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Age Benefits Those With Mental Illness

One of the major findings from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, published in the June 2005 Archives of General Psychiatry, was that most mental disorders usually have their onset in childhood or adolescence. Such early onset, the researchers wrote, is “opposite of the patterns found for almost all chronic physical disorders” (Psychiatric News, July 15, 2005). Thus one might expect mental illnesses to become well entrenched and more difficult to recover from by the time people reach their 50s and beyond. However, this does not seem to be the case, growing evidence suggests.

For example, Jeste and his colleagues longitudinally followed several hundred adults with schizophrenia. As the subjects grew older, and even as their physical functioning deteriorated, their hallucinations and delusions appeared to decrease considerably, and their negative symptoms decreased somewhat as well.

“There is less depression in late life than any of the epidemiologists expected, especially if you control for Alzheimer's, alcoholism, and major depressive disorder,” Vaillant said in an interview with Psychiatric News. “And even if you follow people with major depressive disorder—people who are really quite crippled during their adult lives—they are often doing much better in their 70s, at least if they survive the cigarette smoking that goes with depression.”

A Swiss psychiatrist—Wulf Roessler, M.D., a professor of clinical and social psychiatry at the University of Zurich—found that a surprisingly large number of people in the general Swiss population showed signs of subthreshold psychosis, but that fewer people showed such signs as they aged (Psychiatric News, June 1).

In addition, individuals who abuse substances and those with eating disorders are more likely to get better with age, Joel Paris, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at McGill University in Montreal, told Psychiatric News. The same is even the case for people with borderline personality disorder or antisocial personality disorder, Paris has found (Psychiatric News, July 7, 2006; June 1). Data from short-term follow-ups of individuals with obsessive-compulsive personality disorder suggest that they too tend to improve as they age, said Paris.

“The big exception is bipolar disorder, which sometimes gets worse with age,” Paris pointed out. Jeste, however, is not so sure:“ Actually we have some very preliminary data on bipolar disorder in older people. Some of the older bipolar patients seem to be doing better than some of the younger ones.”

Hypotheses Offered

Relatively little research has been conducted to find out why mental health and mental illness may improve with age. However, some psychiatrists with a special interest in the subject offer possible explanations.

“Brain myelinization is known to increase with age,” said Vaillant, “and the better insulated your brain is, the better it works. Also, the part of the brain that continues to be integrated last is that part of the brain that connects the emotional life—the limbic system—with the frontal lobes. So instead of being uptight or having 'hissy fits' like you did when you were younger, you are able to gracefully modulate your emotional intelligence as you grow older. In other words, emotional intelligence increases with age as memory for names gets worse.”

One reason why the mental health of older people may seem to be better than that of younger ones, Jeste suggested, is that those with poorer mental health die earlier. However, his longitudinal study showing that schizophrenia subjects' mental health sometimes improves with age belies this explanation, he noted.

“My own view is that older people may actually be more vulnerable biologically in some ways. .to developing mental illnesses in late life,” Dan Blazer II, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at Duke University, said. “However, I think that from a psychological perspective, and perhaps a little bit from a social perspective too, there are modifiers that maybe protect older persons from developing mental illnesses later in life. And that is one of the reasons we tend to see a somewhat lower frequency of most of the major mental illnesses in late life, except for the dementing disorders.”

For example, Blazer said, “older people tend to accumulate wisdom, and one part of wisdom is that they have been through a number of events and know how to deal with them. That in turn may protect them when they experience crises in later life, such as physical illness, loss of a spouse, or loss of friends.”

There is also reason to believe that older persons may respond better emotionally to challenges than younger people do because of where they see themselves in life, Blazer suggested. That is, they may be more focused on the present than on the future because they don't have all that many more years to live, and focusing on the present may help them cope better with crises, which in turn helps safeguard their mental health.

A possible reason why individuals with borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and substance abuse often improve as they age, Paris proposed, is because people tend to become less impulsive as they grow older, and impulsivity is a key factor in all three of these disorders.

How Do Findings Affect Practice?

So if people's mental health tends to improve with age—a hypothesis that not all psychiatrists endorse, and one with many exceptions—what are the implications for psychiatric practice?

“We have a cultural belief that it is better to be young than old,” said Paris, “but from the point of view of psychological symptoms, it seems to be untrue. So that's worth noting. Another implication is that people may get better with time with or without intervention, even within a shorter time frame, like five years. So that's useful to know. I think the problem is that we [psychiatrists] end up seeing cases that don't get better. This leads to a bias [in our outlook]. The people who get better disappear, so there is a tendency to see illnesses as more chronic than they really are.”

Vaillant agreed. “Psychiatrists tend to meet the people who are doing badly... .They simply don't have an adequate perspective on adult development.... When you study people for 40 years as I have, you see a different world.” ▪