Prolonged exposure treatment begun a few weeks after a traumatic event reduced the prevalence and severity of posttraumatic stress disorder—but so did waiting five months to start, Arieh Shalev, M.D., said at the annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies in Baltimore in November.

However, while early cognitive therapy also worked well, antidepressants—prominent in current treatment protocols—proved no better than a placebo or time on a wait list in a study of 397 trauma survivors, he said.

The most difficult part of the project was getting trauma survivors into face-to-face contact with clinicians in the first place, said Shalev, a professor of psychiatry at Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem.

“Even if you maximize the chances to provide treatment and promote recovery, many will not use it,” he said.

Clinicians and researchers have paid increased attention recently to studying whether early treatment can prevent PTSD in trauma victims, which treatment should be selected, when it should be applied, and who needs it, said Shalev, who received the society's lifetime achievement award at the meeting for his research on PTSD.

Shalev evaluated early treatment in a randomized clinical trial embedded in a survey of 8,216 trauma admissions to emergency rooms at the two branches of Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem. Most subjects (76 percent) had survived motor vehicle accidents, 13 percent had been injured at work, 4 percent were victims of terrorism, and 7 percent recorded other causes of trauma.

An initial telephone survey reached 4,220 subjects and ruled out 2,232 without PTSD symptoms. Researchers invited 1,470 for a clinical assessment. Nearly half declined, however, and 753 patients completed a clinical assessment.

Ultimately, 397 trauma survivors with acute stress disorder, PTSD, or partial PTSD were invited to begin treatment. Phone interviewers, clinicians, and clinical assessors operated separately and were blinded to each other's actions.

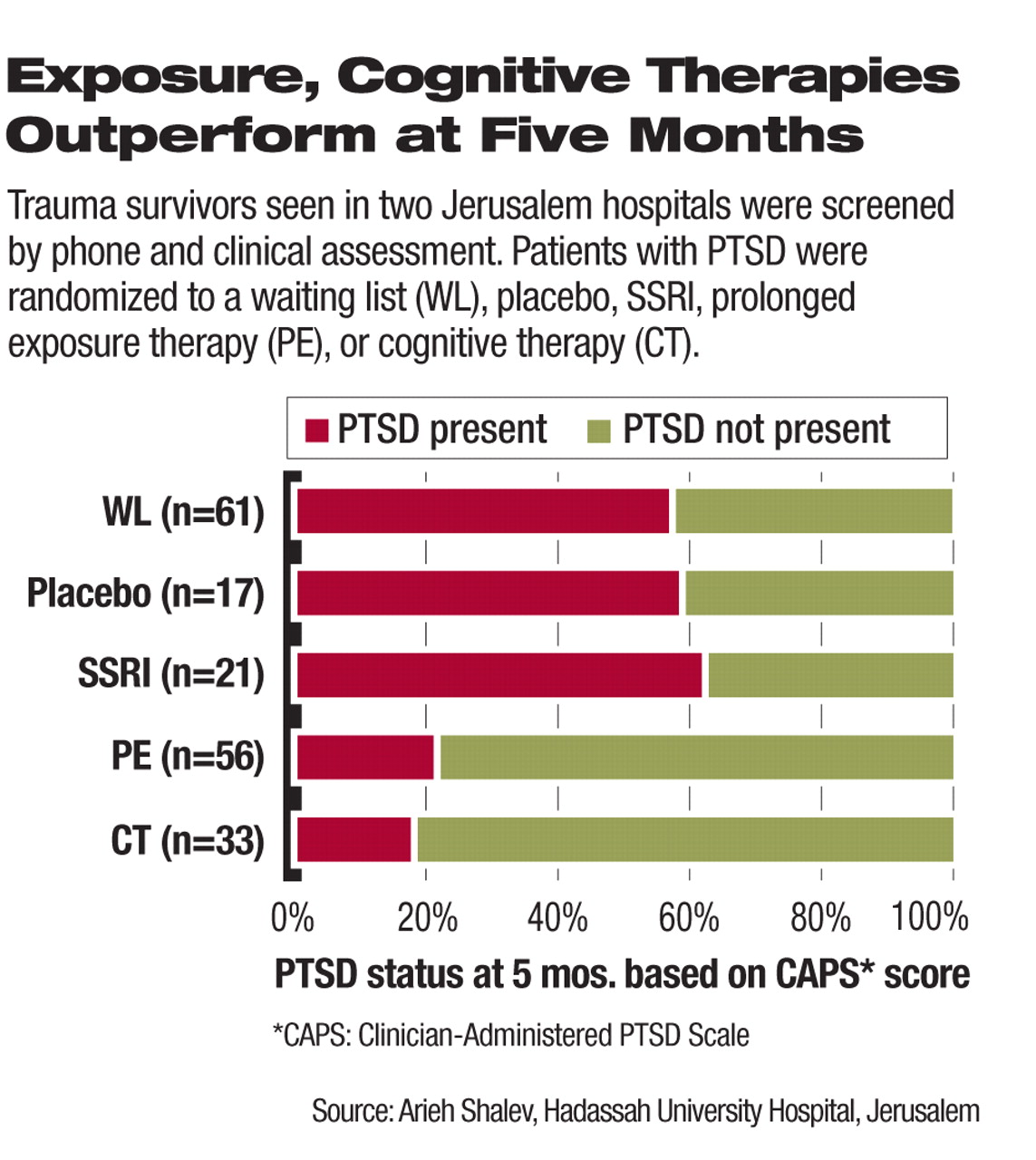

Of patients eligible for treatment, 108 declined, and 289 entered 12 weeks of treatment or control: 113 were put on the wait-list control, 52 were put on on the SSRI antidepressant escitalopram (10 mg to 20 mg) or placebo, 51 had 12 sessions of cognitive therapy, and 73 had 12 sessions of prolonged exposure therapy. Persons who declined or accepted treatment had similar scores on the CAPS Avoidance, CAPS Total, CGI, and BDI scales.

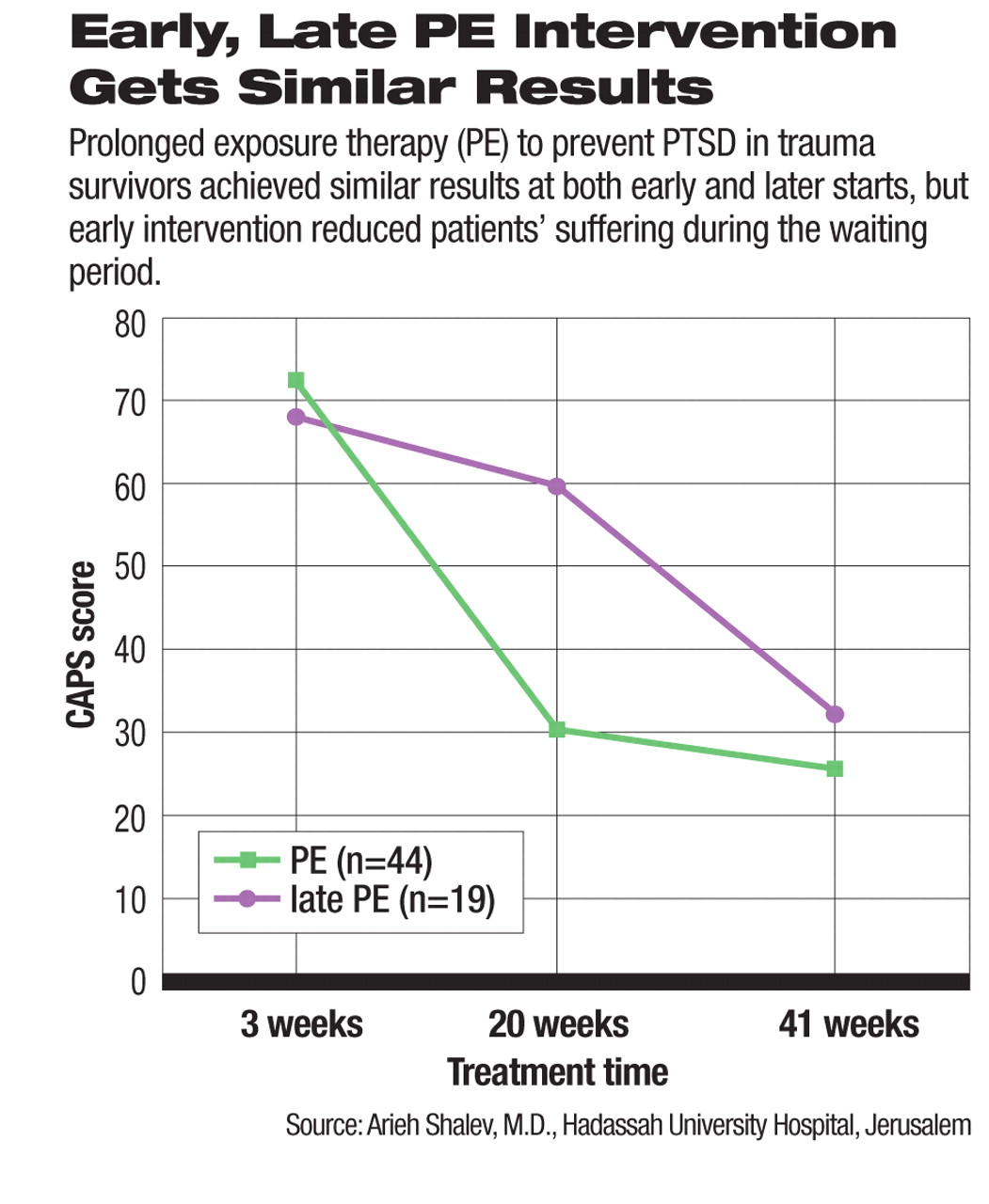

Waitlisted subjects received a biweekly phone call to ensure that they stayed in the study, but if they went into treatment on their own, they were excluded from the final results. Waitlisted subjects were offered prolonged exposure therapy after four months.

One-Third Declined Antidepressant

There was one anomaly in acceptance of treatment. Although at least 96 percent of patients assigned to exposure or cognitive therapy or to the waitlist accepted their assigned treatment, only 67 percent assigned to the antidepressant arm did so.

“Those who declined medication were randomized to other arms of the studies,” said Shalev. “We did not follow the person's preference, but each could decline up to two conditions and was randomized to the remaining two.”

This approach was similar to that used in the STAR*D (Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression) trial, he added.

After four months of treatment, Shalev and colleagues compared outcomes. Patients in all arms of the trial improved during that time. Subjects on prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive therapy improved equally (with CAPS scores of about 30). Both did better than the wait-listed patients and those on escitalopram or placebo (CAPS scores of about 50). Subjects who declined treatment fared worse than those in active treatment or on the waitlist.

The poor showing of the antidepressant cohort comes just weeks after the Institute of Medicine issued a report saying that there was“ insufficient evidence” to affirm the value of SSRIs for treating PTSD.

There were 55 subjects in the trial who recorded some PTSD symptoms but did not meet full DSM-IV criteria. These “partial PTSD” subjects were randomized like all others and fared similarly whether they were on the waitlist, got exposure or cognitive therapy, or declined treatment. That means active treatment should be reserved for those meeting full diagnostic criteria, explained Shalev.

“The decisively ill will need evidence-based treatments,” he said in a later interview. “As for the others—perhaps other approaches like family interventions may work just as well.”

Eight-Month Results Evaluated

When evaluated a third time, at eight months, patients who had been in the original exposure arm and those from the waitlist who started exposure therapy at four months showed equal improvement. A subset of waitlisted patients who recovered without treatment did equally well compared with this group.

“Early or late entry into treatment produces equal results at eight months, but early treatment reduces people's suffering,” said Shalev.“ Only when they start treatment do symptoms decline.”

Studies by Shalev and others on early interventions provide useful evidence, but the type of traumatic event and its context cannot be ignored in future research, commented Robert Pynoos, M.D., of the National Center for Child Traumatic Stress at UCLA, following Shalev's talk.

“Early intervention has the potential to speed recovery, but we have to know about the intervening issues rather than talk only about treating a disorder,” said Pynoos.

Shalev's study has not yet been published. It was supported by the Jerry Lee Foundation, UJA Federation of New York, CMS Companies, and National Institute of Mental Health. ▪