The latest round of results from the National Institute of Mental Health's (NIMH) Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study strongly suggest that both effectiveness and tolerability of an antipsychotic medication depend substantially on the clinical context in which it is given. And that context is impacted by the heterogeneity of the patients being treated and of the antipsychotic medications themselves.

“There are considerable individual differences in response to antipsychotic treatment that likely depend on as-yet-unknown patient characteristics,” T. Scott Stroup, M.D., M.P.H., and his coauthors reported in the March American Journal of Psychiatry. Stroup is an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine.

The latest report is the fourth in a series presenting results from the complex CATIE protocol. Nearly 1,500 patients began phase 1 and 1A of the study. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either one of the Second-Generation Antipsychotics (SGAs) olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal), or ziprasidone (Geodon) or the First-Generation Antipsychotic (FGA) perphenazine (Trilafon). Patients in phase 1A had tardive dyskinesia (TD) at the outset of the study and were therefore randomly assigned only to one of the four SGAs, to avoid what was thought at the time to be a higher risk of TD associated with FGAs.

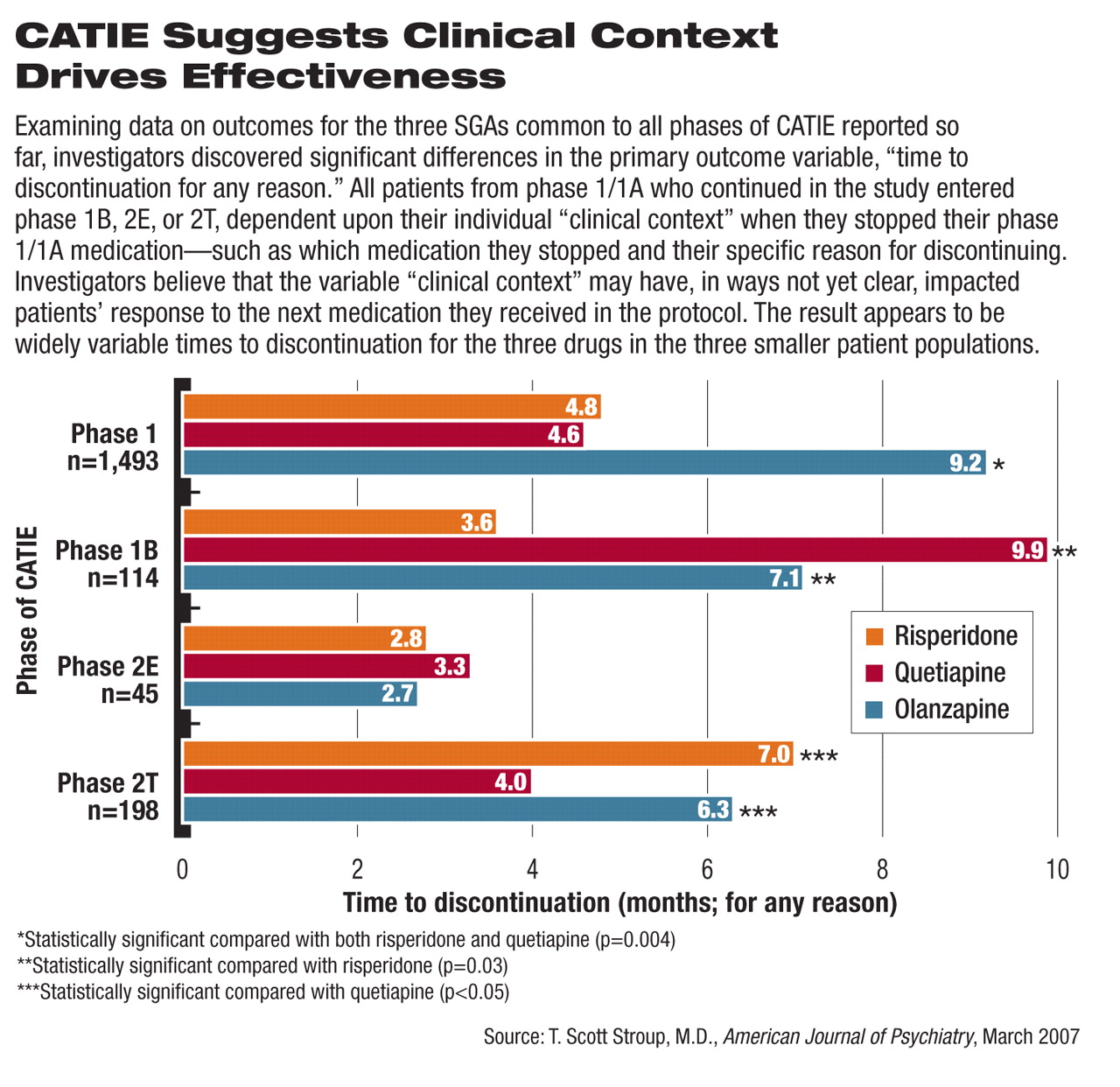

Of the 1,493 patients who took at least one dose of their assigned phase 1/1A medication, patients who then chose to stop taking that assigned medication prior to the end of the 18-month study was offered continued care within the CATIE protocol, regardless of the patients' reason for stopping their study medication. Patients who stopped taking perphenazine during phase 1 could be randomly assigned to take an SGA in phase 1B before possibly proceeding on to phase 2 of the study. Patients who discontinued their phase 1/1A assigned SGA due to lack of effectiveness were randomly assigned to a different SGA in phase 2E of CATIE, while those who discontinued due to lack of tolerability went on to phase 2T of CATIE (see

chart below).

Stroup and his colleagues detailed outcomes from phase 1B, which included 114 of the 192 patients (59 percent) who stopped taking perphenazine, for any reason. They were randomly assigned to one of three SGAs: olanzapine, quetiapine, or risperidone.

During phase 1B, as in every phase of the CATIE protocol, the primary outcome measure was time to discontinuation of the assigned medication, for any reason.

A companion article in the March American Journal of Psychiatry, with Marvin Swartz, M.D., as lead author, gave an analysis of quality-of-life outcomes from the CATIE trial. Coverage of that analysis will appear in the next issue of Psychiatric News.

Quetiapine Looks Better After FGA

Stroup and his colleagues said in their latest report that 77 of the 114 patients (68 percent) stopped taking their assigned 1B medication prior to the end of the study, a percentage similar to that found in the other three CATIE reports.

The time to discontinuation in phase 1B was significantly longer for patients taking quetiapine (an average of 9.9 months) or olanzapine (7.1 months) than for patients taking risperidone (3.6 months). The difference between time to discontinuation with quetiapine compared with olanzapine was not statistically significant; however, the differences between both quetiapine and olanzapine compared with risperidone were significant (p = 0.03).

Secondary outcomes included discontinuation due to efficacy, intolerability, or “patient decision.” In addition, clinical outcome measures including change from baseline in scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale and the Clinical Global Impression–Severity scale were tracked, as were scores on the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale, Barnes Akathisia Scale, and Simpson-Angus EPS Scale to look for treatment-emergent neurological adverse events.

Other outcome variables included rates of rehospitalization due to exacerbation, adverse events, weight change, and changes in blood chemistry (glucose, lipids, triglycerides, and hemoglobin A1c).

The only adverse events for which rates were statistically significantly different between the three treatment groups were weight gain and increases in total cholesterol and triglyceride levels, with patients on olanzapine experiencing the greatest increases in each. A weight gain of more than 7 percent of baseline body weight occurred in 36 percent of the patients taking olanzapine, 24 percent taking quetiapine, and 14 percent taking risperidone. Prolactin levels increased on average 13.7 ng/ml in patients taking risperidone over 12 months, while prolactin fell in patients taking olanzapine (-12.3 ng/ml) and quetiapine (-10.8 ng/ml).

Clinical Course Makes a Difference

“The results of phase 1B are a bit different from those in the previously reported phases, although again we found olanzapine to be effective overall—particularly so with patients who had stopped taking perphenazine because of continued symptoms,” Stroup said during a press briefing. “However, olanzapine was again associated with a fair amount of weight gain. What is different in phase 1B is that quetiapine was at least as effective—if not more so overall—as olanzapine, and both olanzapine and quetiapine were significantly more effective than risperidone.”

Stroup added that for patients who failed on perphenazine due to intolerability, “quetiapine had a substantial advantage over the other drugs. This sort of confirms a clinical hunch that if a patient doesn't do well on drug A, they might do well in trying a drug that is substantially different.”

In phase 1, patients taking olanzapine stayed on their medication significantly longer than did patients taking risperidone or quetiapine (see

chart). Patients taking perphenazine during phase 1 fared about the same as those taking risperidone or quetiapine, based on time to discontinuation (

Psychiatric News, October 21, 2005).

Phase 2E of CATIE (referred to as “the efficacy pathway” because patients entered 2E primarily due to lack of efficacy of their phase 1 antipsychotic) included patients who agreed to the possibility of being randomly assigned to clozapine in addition to other SGAs. CATIE investigators found that patients taking clozapine had a significant advantage in terms of time to discontinuation, followed by those on quetiapine, olanzapine, and risperidone. However, no significant differences were found among the three latter SGAs in phase 2E.

Phase 2T (the “tolerability pathway”) included patients who discontinued their phase 1 medication due to intolerable side effects or because they were unwilling to receive clozapine. The time to discontinuation for any reason was significantly longer for patients taking risperidone and olanzapine, compared with those taking quetiapine (Psychiatric News, April 21, 2006).

Getting Closer to 'Road Map'

“As we look at more and more data,” Stroup said, “we are learning about which drugs to choose in specific situations.” The phase 1B results, he added, “reinforce the fact that finding the most effective medication for each patient sometimes means trying multiple medications. [The results] remind us of the considerable variability in clinical circumstances and of our need to be responsive to an individual's needs and preferences.”

In an accompanying editorial, Stephen Marder, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of California at Los Angeles, hypothesized that subtle problems with movement disorders, a known side effect of the FGAs, limit their usefulness in some patients. Marder suspects that the patients in phase 1B, all of whom discontinued perphenazine, may have been more prone to mild extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Those mild EPS may not have been significant enough to be recognized by study investigators as an adverse effect or may not have been adequately verbalized by patients, yet were troubling to the patients.

“The editorial by Marder points to the often subtle clinical experience of neurological side effects from antipsychotic medications that may have induced patients to discontinue these treatments in the CATIE study,” said Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., director of APA's Division of Research and the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education.“ By understanding patient vulnerabilities and known side effects of specific medications, clinicians have the potential for greater tailoring of treatment plans for individual patients when the full range of medications is available on formularies.”

“What the CATIE data are piecing together,” commented Jeffrey Lieberman, M.D., director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the principal investigator overseeing CATIE, “is the different components of a map. Up till now, trying to match the right patient with the right medication has all been done by trial and error.”

CATIE represents the first time nearly all of the SGAs have been studied within the context of one clinical trial and given under controlled conditions to the same defined patient population, Lieberman told Psychiatric News.

Lieberman believes the CATIE investigators are approaching the point of being able to put together a chart that suggests the most likely antipsychotic medication to use to promote recovery, based on specific patient presentations.