The omega-3 fatty acids—which show promise against a range of psychiatric illnesses and can be obtained by eating fish or taking supplements—can reduce symptoms in suicidal persons.

So suggest two studies in the February British Journal of Psychiatry. Both studies were headed by psychiatrist Malcolm Garland, M.D., who was affiliated with Beaumont Hospital in Dublin, Ireland, when the studies were conducted. He is now on staff of St. Ita's Hospital in Dublin.

First Garland and colleagues launched a study to learn whether suicidality is associated with low levels of the omega-3 fatty acids in the body. The subjects were 80 patients at a university teaching hospital, half of whom were suicidal and who had been brought to the hospital's emergency room. The other half were nonsuicidal patients in the hospital's medical day ward who matched the subjects on age, gender, and amount of fish eaten weekly.

The researchers took blood samples from both groups and then compared the levels of omega-3 fatty acids in the blood of the suicidal group with those in the control group, taking possibly confounding factors such as social class, exercise, smoking, or alcohol intake, into consideration. They found that the levels were significantly lower in the suicidal group.

They also assessed both groups for depression and impulsivity. Not surprisingly, the suicidal group scored higher on both depression and impulsivity than the control group did, since depression and impulsivity are risk factors for suicide. The researchers then looked to see whether there was any relationship between subjects' depression and impulsivity scores and the level of omega-3 fatty acids in their blood. There was, they found. Low omega-3 fatty acid levels were significantly and inversely related to high depression and impulsivity scores.

So it looked as if persons with a paucity of omega-3 fatty acids in their bodies might be more vulnerable to suicide than persons with higher levels of the acids and that the mediating factors might be depression and impulsivity.

The researchers then decided to investigate whether giving omega-3 fatty acid supplements to suicidal individuals keeps them from engaging in self-harm.

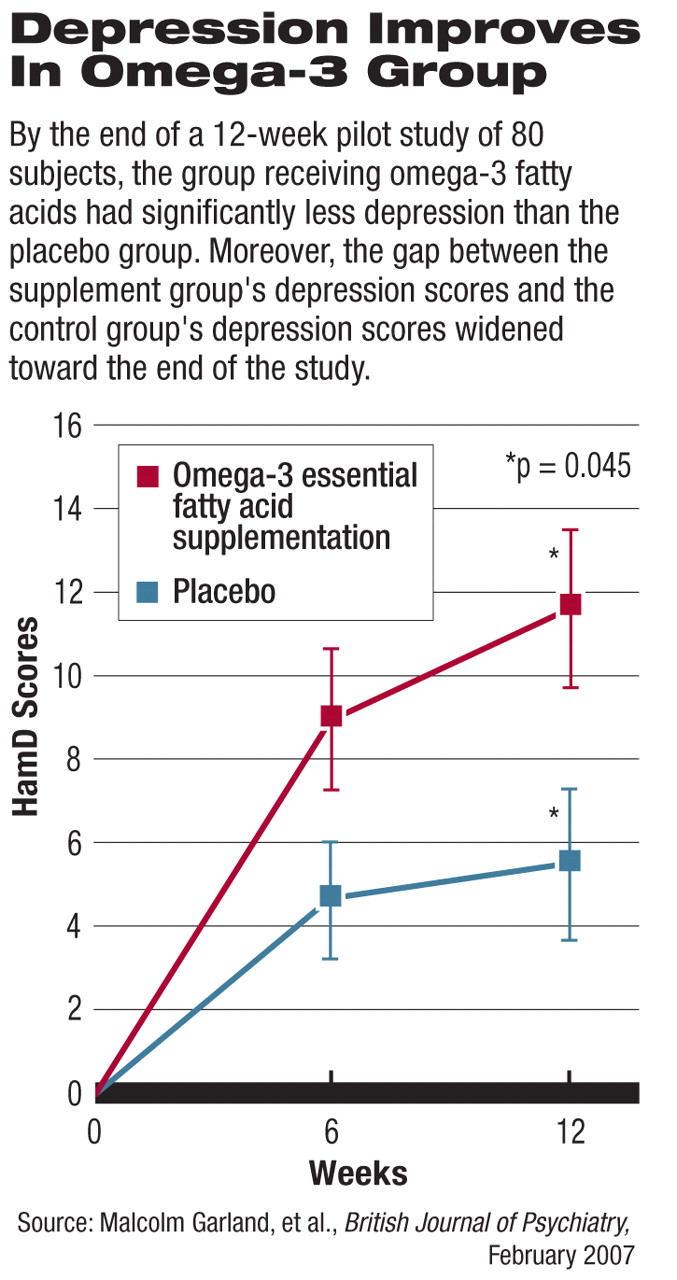

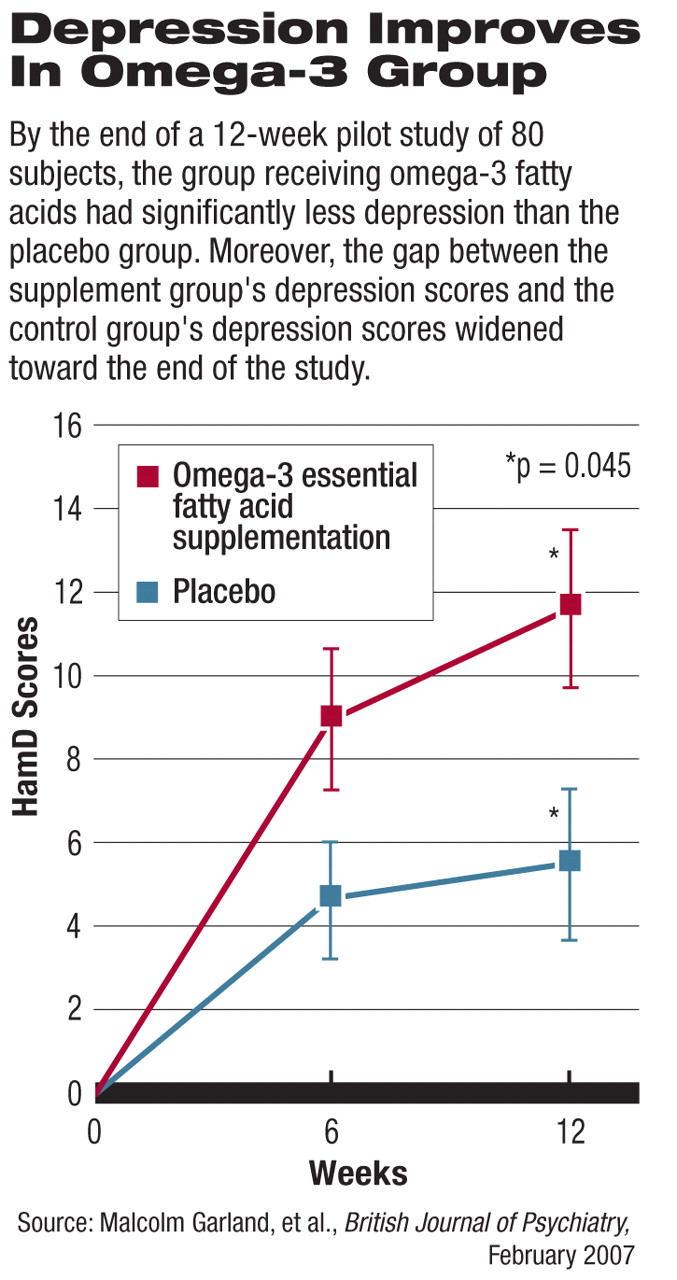

Forty-nine individuals who had tried repeatedly to kill themselves were randomized to receive either omega-3 fatty acid supplements or a placebo for 12 weeks in addition to standard psychiatric care. Subjects were tested both at the start of the study and 12 weeks later in six psychological domains—depression, suicidal ideation, daily stress perception, impulsivity, aggression, and hostility. Changes in scores over the 12-week period were calculated for each subject, and score changes the supplement group experienced were compared with changes registered by the control group.

By the end of the 12-week period, the group receiving the supplement had significantly less depression, suicidal ideation, and daily stress perception than the control group did—especially less depression. Moreover, the gap between the supplement group's depression scores and the control group's depression scores widened even more toward the end of the study, suggesting that the supplement group might have experienced an even more dramatic drop in depression if it had received supplements for a longer period.

The supplement group's final scores for impulsivity, aggression, and hostility did not differ, however, from those of the control group, and seven individuals in the supplement group attempted to harm themselves, just as seven in the control group did.

Thus, the true value of omega-3 supplementation as a suicide-prevention tool can be determined only by a large-scale, multicenter, long-term investigation, Garland and his team concluded.

The studies were partially funded by the Institute of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago. The remaining costs were paid by the researchers.

First Garland and colleagues launched a study to learn whether suicidality is associated with low levels of the omega-3 fatty acids in the body. The subjects were 80 patients at a university teaching hospital, half of whom were suicidal and who had been brought to the hospital's emergency room. The other half were nonsuicidal patients in the hospital's medical day ward who matched the subjects on age, gender, and amount of fish eaten weekly.

First Garland and colleagues launched a study to learn whether suicidality is associated with low levels of the omega-3 fatty acids in the body. The subjects were 80 patients at a university teaching hospital, half of whom were suicidal and who had been brought to the hospital's emergency room. The other half were nonsuicidal patients in the hospital's medical day ward who matched the subjects on age, gender, and amount of fish eaten weekly.