Can experiencing trauma plunge people into psychosis? Research reported in the April British Journal of Psychiatry suggests that it can indeed do so.

In 1997 the Australian Bureau of Statistics conducted the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Survey respondents answered questions regarding their mental health, including whether they had experienced any trauma and/or delusions.

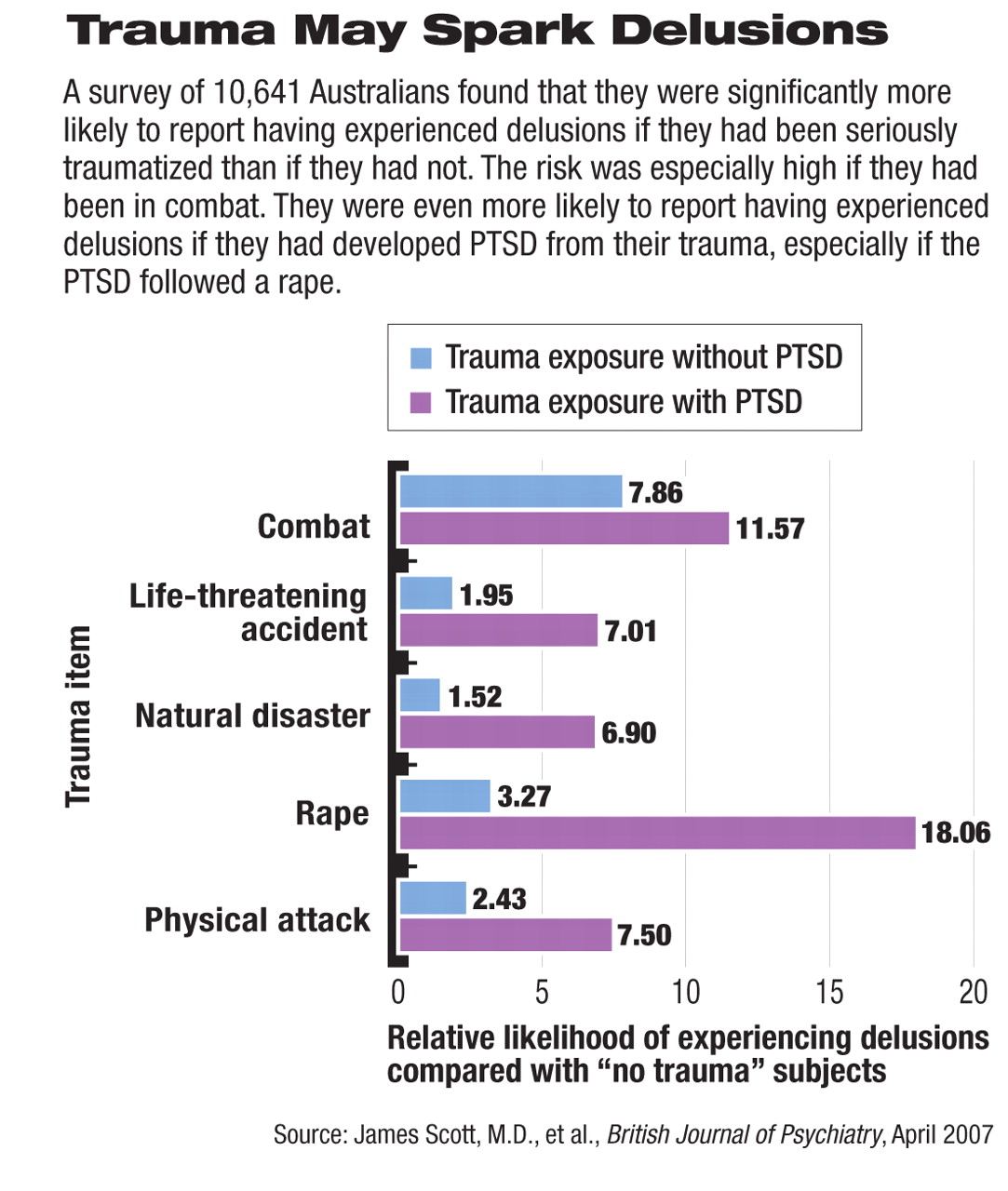

Of the 10,641 persons surveyed, 5,725 (53.8 percent) had been exposed to a trauma, but had not developed posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from it, 379 (3.6 percent) had been exposed to a trauma and had developed PTSD, and 478 (4.49 percent) reported delusional experiences.

James Scott, M.D., a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the Royal Children's Hospital in Herston, Queensland, Australia, and his colleagues decided to use the trauma and delusion findings from the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing to conduct their own study. They wanted to see whether individuals who experienced various types of trauma also experienced delusions. The rationale behind their hypothesis, Scott explained to Psychiatric News, was that “an emerging body of evidence suggests an association between psychotic symptoms and abuse in childhood. It was thus illogical to us that psychotic symptoms should be confined to one specific type of trauma, so we were interested in examining if the association existed with other types—say, natural disaster, combat, or physical violence.”

Hypothesis Confirmed

Their analyses of the survey's traumadelusion results confirmed their hypothesis. Individuals who had experienced trauma were more likely to have experienced delusions than were individuals who had experienced no trauma. The difference was statistically significant.

They also found a dose-response relationship between trauma and delusions. The relative risk varied but remained significant with exposure to all traumas. For example, those who had experienced one or two traumas were three times more likely to have had delusions as were nontraumatized persons, but those who incurred five or more traumas were 10 times more likely to have done so.

Moreover, those who had developed PTSD after trauma were more likely, to a statistically significant degree, to have delusions than were indiv iduals who had not developed PTSD after trauma. For instance, whereas only 8 percent of those who had been in combat had delusions, 12 percent of those who had developed PTSD in the wake of combat did, and whereas only 3 percent of those who had been raped had delusions, 18 percent of those who incurred PTSD after a rape did. “We were surprised by the size of the relative risks of delusional experiences with PTSD,” Scott said.

Finally, the links between various types of trauma and delusions and the links between PTSD and delusions remained statistically significant even after possibly confounding factors were considered. The factors included age, gender, marital status, socioeconomic status, employment status, country of birth, urban living, a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and alcohol or marijuana dependence.

Researchers Speculate on Causes

In their study report, Scott and his group speculated on how trauma might cause delusions or other types of psychotic symptoms. For example, trauma might lead to altered stress hormones, which might then catalyze the neurobiological mechanisms contributing to the onset of psychosis.

They also suggested that the evidence linking trauma and psychosis might help explain why persons living in urban areas are especially susceptible to schizophrenia. However, they said that the 87 persons in their survey sample who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia were not significantly more likely than other survey respondents to have been traumatized.

As for the implications of their findings, they noted, clinicians should ask people with psychot ic sy mptoms about past exposure to traumatic events. Also, if trauma can contribute to development of psychosis, then prompt treatment of trauma may not only prevent PTSD, but trauma-induced psychosis as well.

However, the most important implication of their study, Scott said,“ is the overlap of symptoms between psychotic disorders and PTSD. This may create diagnostic uncertainty where people with PTSD are misdiagnosed as having a psychotic illness or, alternatively, where people with an emerging psychotic illness who have a history of exposure to trauma are misdiagnosed as having PTSD, and psychosis intervention is delayed. At this time, the symptom overlap between these disorders potentially creates diagnostic confusion and may result in administration of inappropriate treatment.”

There was no external financial support for this study.