When it comes to treating bipolar depression, a mood stabilizer alone seems to be just as effective as a mood stabilizer combined with an antidepressant.

Moreover, pharmacotherapy coupled with nine months of psychotherapy for bipolar depression seems to be more efficacious than pharmacotherapy combined with a brief psychosocial intervention.

The first result was posted on the New England Journal of Medicine Web site on March 28; the latter was published in the April Archives of General Psychiatry. Both investigations were headed by Gary Sachs, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Harvard University.

The findings are also the latest to emerge from the large, multisite Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), a $27 million clinical trial funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (Psychiatric News, March 3, 2006). “STEP-BD is helping us identify the best tools—both medications and psychosocial treatments—that patients and their clinicians can use to battle the symptoms of this illness,” NIMH Director Thomas Insel, M.D., said in a press release accompanying the latest findings.

Monotherapy Worked as Well

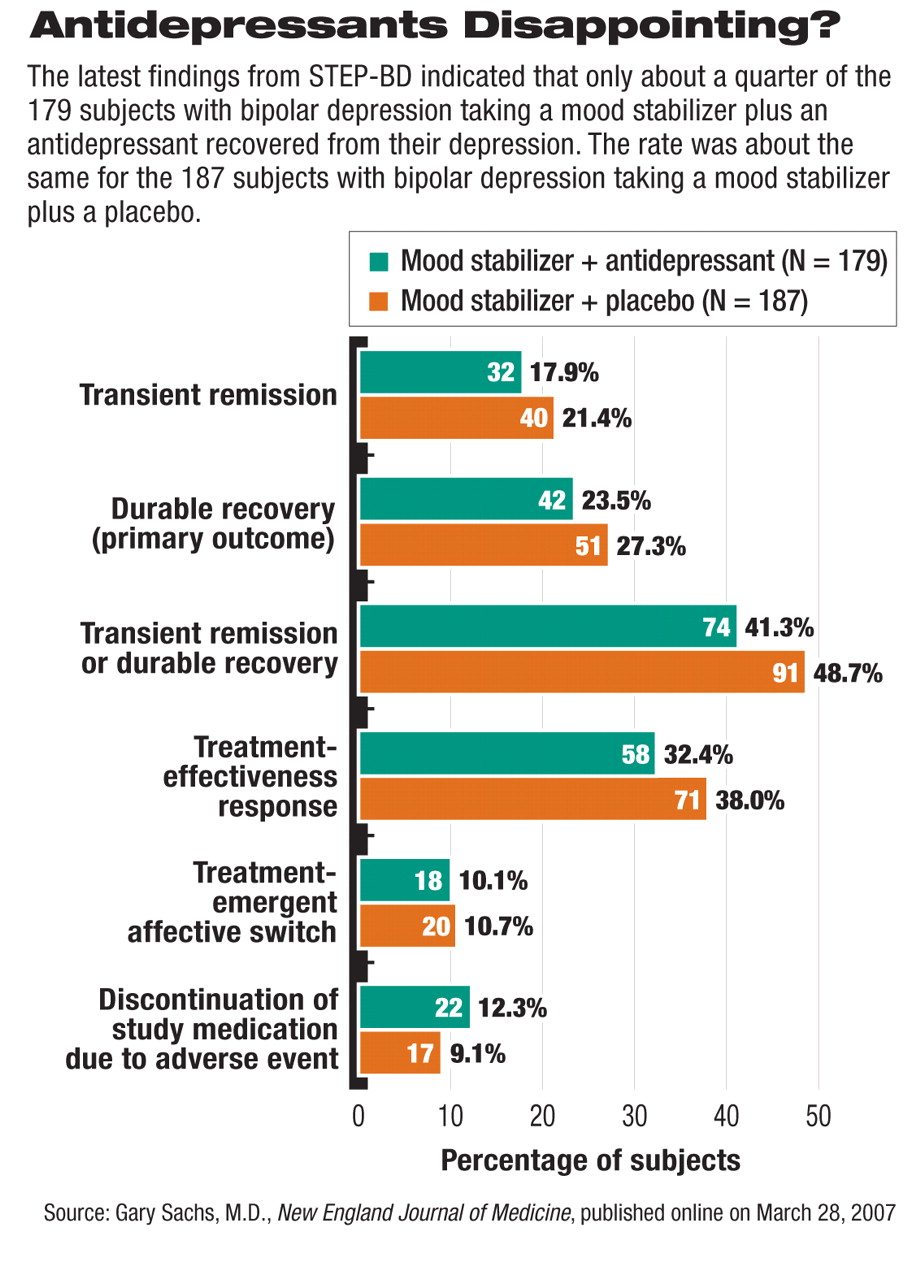

Although episodes of depression are the most common cause of disability among persons with bipolar disorder, and while antidepressants in conjunction with mood stabilizers are commonly used to treat bipolar depression, there is only limited evidence of their short-term or long-term efficacy. So in their first investigation, Sachs and his team randomly assigned 366 bipolar patients who were experiencing a depression to receive up to 26 weeks of either a mood stabilizer plus an antidepressant or a mood stabilizer plus a placebo.

The antidepressants used were paroxetine and bupropion since both are associated with low rates of switching patients to mania early in the course of treatment and are the antidepressants most commonly prescribed for bipolar depression. Mood stabilizers were initially limited to lithium, valproate, a combination of lithium and valproate, or carbamazepine.

In 2004 the protocol was amended to define mood stabilizers as any antimanic drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

The scientists then looked to see how many subjects in each group experienced a “durable recovery”—that is, eight consecutive weeks of a nondepressed, reasonably happy mood. This outcome measure, Sachs explained to Psychiatric News, “is a much more stringent criterion than that used in prior studies, and we believe it represents a much more clinically meaningful measure of outcome.”

They found that durable-recovery evidence was about the same for both groups—24 percent for the group getting an antidepressant and 27 percent for the placebo group. Thus, “for the treatment of bipolar depression, we found that mood-stabilizing monotherapy prov ides as much benefit as treatment with mood stabilizers combined with a standard antidepressant,” the researchers concluded.

Psychotherapy Helps

In the second investigation, Sachs and his group wanted to determine whether intense psychotherapy could aid and hasten recovery from bipolar depression. They selected 293 depressed bipolar patients to answer this question and randomly divided them into two groups. They made sure that the groups did not differ significantly at the time of randomization on demographics, illness history, current clinical state, or types of medications they were taking for their bipolar illness.

One group was assigned to a control condition called “collaborative care.” It consisted of three sessions over a six-week period to educate subjects in the diagnosis, management, and treatment of bipolar disorder; the importance of medication adherence; how mood states can bias thinking; how to improve relationships; and other aspects of dealing with a bipolar illness.

The other group was assigned to an experimental condition, which involved up to 30 sessions of intense psychotherapy over nine months. It consisted of an enhanced version of collaborative care plus cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), an enhanced version of collaborative care plus family-focused therapy, or an enhanced version of collaborative care plus interpersonal and social-rhythm therapy.

For example, individuals in the CBT arm worked on challenging negative thoughts or dysfunctional beliefs. Those in the interpersonal and social-rhythm therapy arm worked on resolving interpersonal problems and stabilizing their times for eating, sleeping, and exercise in hopes that a stable lifestyle would help stabilize their moods. And those in the family-focused therapy arm, along with their relatives, were versed in how stress can trigger manic or depressive episodes, how to communicate better with each other, and how to develop a relapse-prevention plan.

Subjects' progress or lack of progress toward recovery was tracked from the start of the study to 12 months later.

At the end of the year, 64 percent of subjects who had received intensive psychotherapy were no longer depressed, whereas 52 percent of subjects who had received the control condition were. This was a statisticaly significant difference. Moreover, the average time to recovery among subjects in the intensive psychotherapy group was 113 days, while it was 146 days among subjects in the control group.

Furthermore, the researchers could find no significant differences among the three intensive psychotherapies in their ability to aid and sustain recovery from depression. The reason, they said, may be due to the fact that their inquiry did not include enough subjects to detect such differences or that the psychotherapies, which are similar in many ways, are truly comparable in effectiveness.

Thus, “given the limited benefits of antidepressant medications in patients with bipolar depression who are taking mood stabilizers,” Sachs and his team concluded in their Archives of General Psychiatry report, “referral for intensive psychosocial treatment seems to be an especially important addition to clinical care.”

But how about cost? “Intensive treatments [such as these], although seeming to be more effective than brief treatments in hastening recovery from episodes, maintaining stability, and delaying recurrences, are also more costly,” Sachs and his group said. However, “treatment-associated costs must be carefully balanced against the potential gains for patients in functioning and quality of life and, possibly, reductions in rates of hospitalization or polypharmacy.”

Sachs told Psychiatric News that the most crucial take-home messages from these two studies are that “it is not necessary to add a standard antidepressant medication when starting treatment for patients with bipolar depression [and that] the strongly positive outcomes for the psychosocial interventions suggest that these treatments should always be offered to bipolar depressed patients.”