The suicide rate of U.S. youth remains elevated after a decade of decline that ended in 2003, according to a study in the September 3 Journal of the American Medical Association.

In this study, researchers led by Jefffrey Bridge, Ph.D., a principal investigator at the Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital and an assistant professor at the Ohio State University College of Medicine, analyzed 1996-2005 data on suicide deaths of youngsters aged 10 to 19 and found, after the spike in 2004, that the suicide rate dropped slightly but remained significantly higher than the trend in previous years.

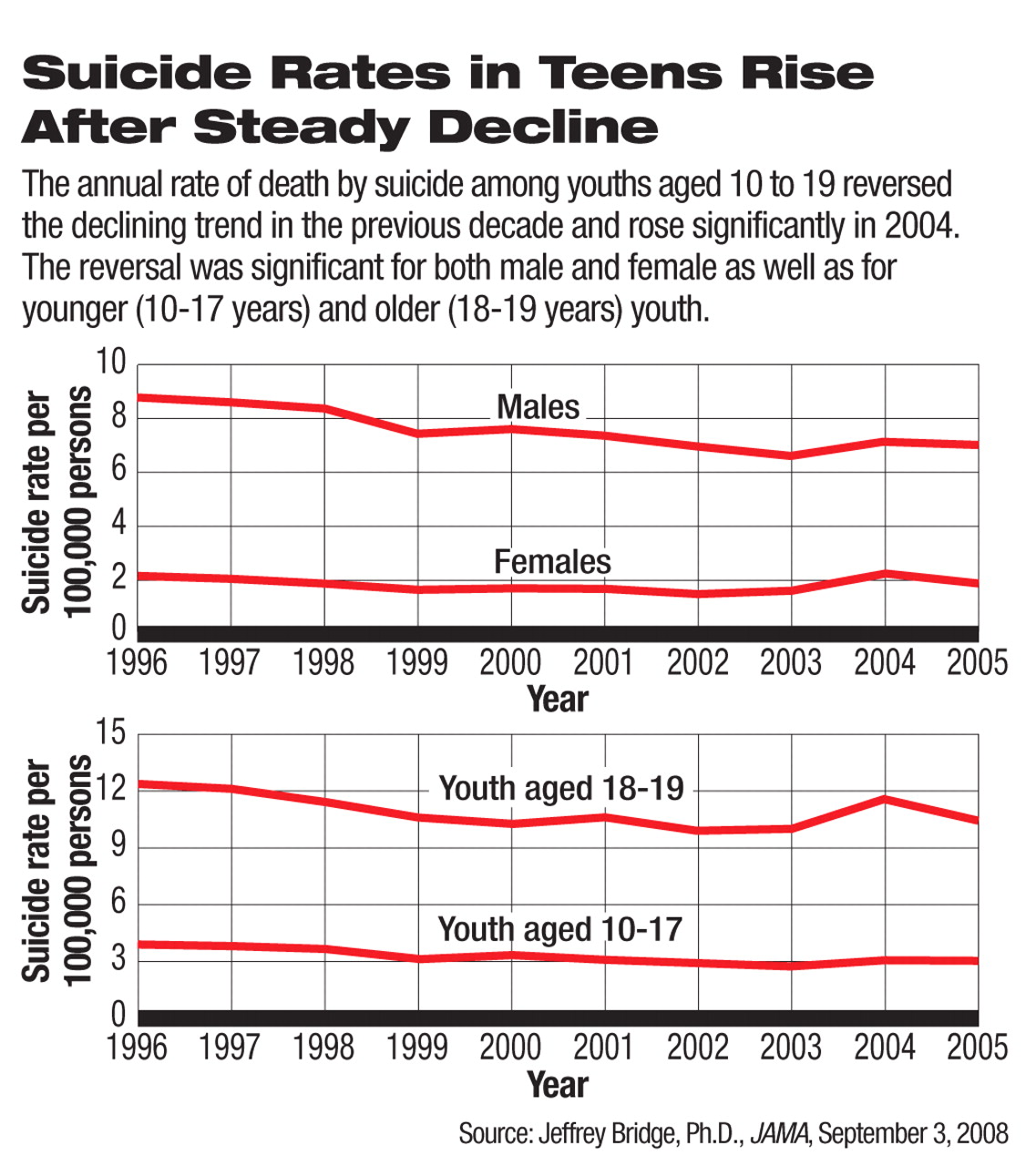

The estimated rate of suicide deaths in 10- to 19-year-olds was 4.49 per 100,000 in 2005, a small reduction from 4.74 per 100,000 in 2004 but still significantly higher than the projected rate based on the steadily declining trend from 1996 to 2003.

The analysis used data from the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, a division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

After years of decline, the suicide death rate in youth rose in 2003 and more sharply in 2004, according to the CDC's announcement last year ((Psychiatric News, October 5, 2007). The 18 percent increase from 2003 to 2004 had been the highest one-year jump in the previous 15 years. The unexpected spike caused heated debates over its causes, and many, including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), were unsure whether this was an isolated incident. The new study suggests that the elevated trend persisted in 2005 and thus may not be an anomaly.

The suicide death rate in 2005 was significantly higher than the 1996-2003 trend predicts in both male and female teenagers and in both the younger (10 to 17) and older (18 and 19) subpopulations.

Many experts have suspected a connection between the rise in suicide deaths and the black-box warning on suicidal ideation and behavior in young patients associated with antidepressant drugs that was imposed by the FDA in 2004 and the accompanying publicity (Psychiatric News, October 5 and June 15, 2007). Studies have shown that the use of antidepressants declined or stopped increasing, especially among children and adolescents, after the FDA issued the warning (Psychiatric News, February 1). These observations have raised concerns by psychiatrists and others about inadequate treatment for depression in young patients that may pose a greater risk of suicide than the antidepressant-triggered suicidal ideation and behaviors.

“The fact that the adolescent suicide rate remains elevated is very disturbing,” David Fassler, M.D., a pediatric psychiatrist and a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont and APA secretary-treasurer, commented. “After over a decade of steady decline, we're seeing a definite and sustained increase.” Meanwhile,“ we've seen a significant reduction in prescriptions for young people since the FDA imposed a black-box warning.”

The temporal parallel, however, cannot prove a correlation between the black-box warning and the rise in youth suicide rates. The study authors proposed several possible explanations for the observed trend such as changes in alcohol use or firearm access, influence of Internet social networks, and increased suicide among military personnel in this age category, as well as more patients with untreated depression after the black-box warning was issued.

“Attention must now be directed toward understanding whether this increase in the youth suicide rate... reflects an emerging public health crisis,” they wrote.

“It is very difficult to prove a causal relationship between the increase in the youth suicide rate and the decrease of antidepressant prescribing,” Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., director of APA's Division of Research and the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education, told Psychiatric News. “One finding is very clear—the black-box warning did not reduce completed suicides, which should have been the ultimate goal of the FDA action.”

He pointed out that, because of ethical reasons, researchers cannot conduct a randomized, controlled experiment to assess whether a link exists between completed suicide and decreased availability of treatment. “One possibility is to conduct a quasi-experiment and withdraw the black-box warning to see if there is a subsequent reduction in suicide rate,” he said.

Regier explained that the FDA had relied on relative rates of spontaneously reported suicidal ideation or behavior from depressed people on medication compared with those on placebo in clinical trials in the agency's decisions about whether to require the black-box warning for antidepressants.

“Epidemiologists, FDA staff, and psychiatric experts have identified many methodological problems of relying on spontaneous reports of suicidal ideation in randomized clinical trials,” Regier pointed out. “The FDA now advocates using prospective systematic assessments of suicidal risk in future clinical trials for all medications that may be associated with such risks.” However, the black-box warning for antidepressants remains standing.

“In the recent FDA hearing on suicidal risks of antiseizure and mood-stabilizing medications, we heard testimonies suggesting that the societal effects of black-box warnings go beyond informing physicians for better monitoring and vigilance, but may be more complex and unpredictable than expected,” Regier noted.

Earlier this year, the FDA intended to require a black-box warning for antiseizure medications based also on spontaneous reports of suicidal ideation and behavior in clinical trials (Psychiatric News, August 15). The experts on the advisory committee, however, voted to recommend against a black-box warning, citing concerns that patients' fear of taking these medications would lead to far more deaths from untreated seizures and bipolar disorder than from the possible drug-related suicidal ideation.

“Not all children and adolescents with depression need medication, but for those who do, it can be extremely effective and even lifesaving,” said Fassler. He urged the FDA to monitor the consequences of its regulatory decisions and modify its actions if evidence suggests it is necessary.

“The question now for the FDA is what epidemiological evidence would be enough to prompt the agency to reconsider its previous decision about the black-box warning because of these reported signs of unintended consequences,” said Regier.

“Suicide Trends Among Youths Aged 10 to 19 Years in the United States, 1996-2005” is posted at<jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/300/9/1025>.▪