Pregnant women with bipolar disorder and their physicians face a dilemma: stay on mood-stabilizing medications, which carry risks of causing birth defects, or discontinue the medications and brace for the possibility of relapse.

The possibility of relapse due to interrupted pharmacotherapy has been quantified in a study published in the December 2007 American Journal of Psychiatry, which warns that pregnant women with bipolar disorder who discontinue mood stabilizers are much more likely to suffer the return of their illness than those who continue taking the medications.

Adele Viguera, M.D., and colleagues at Harvard Medical School and Emory University conducted this observational study in which they prospectively followed 89 women, all of whom had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, from pregnancy or the planning of pregnancy to one year after the childbirth to trace the course of the disease.

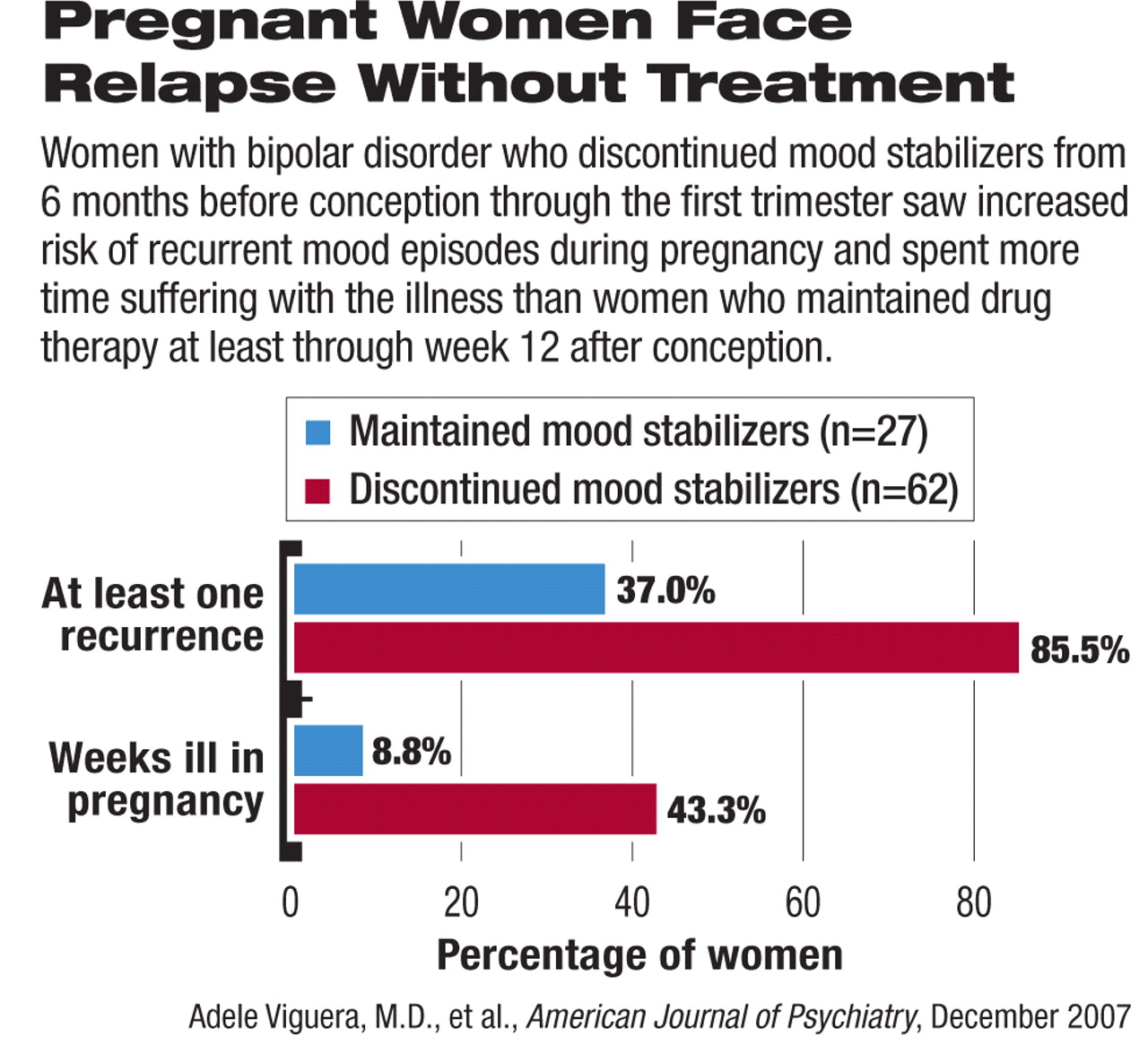

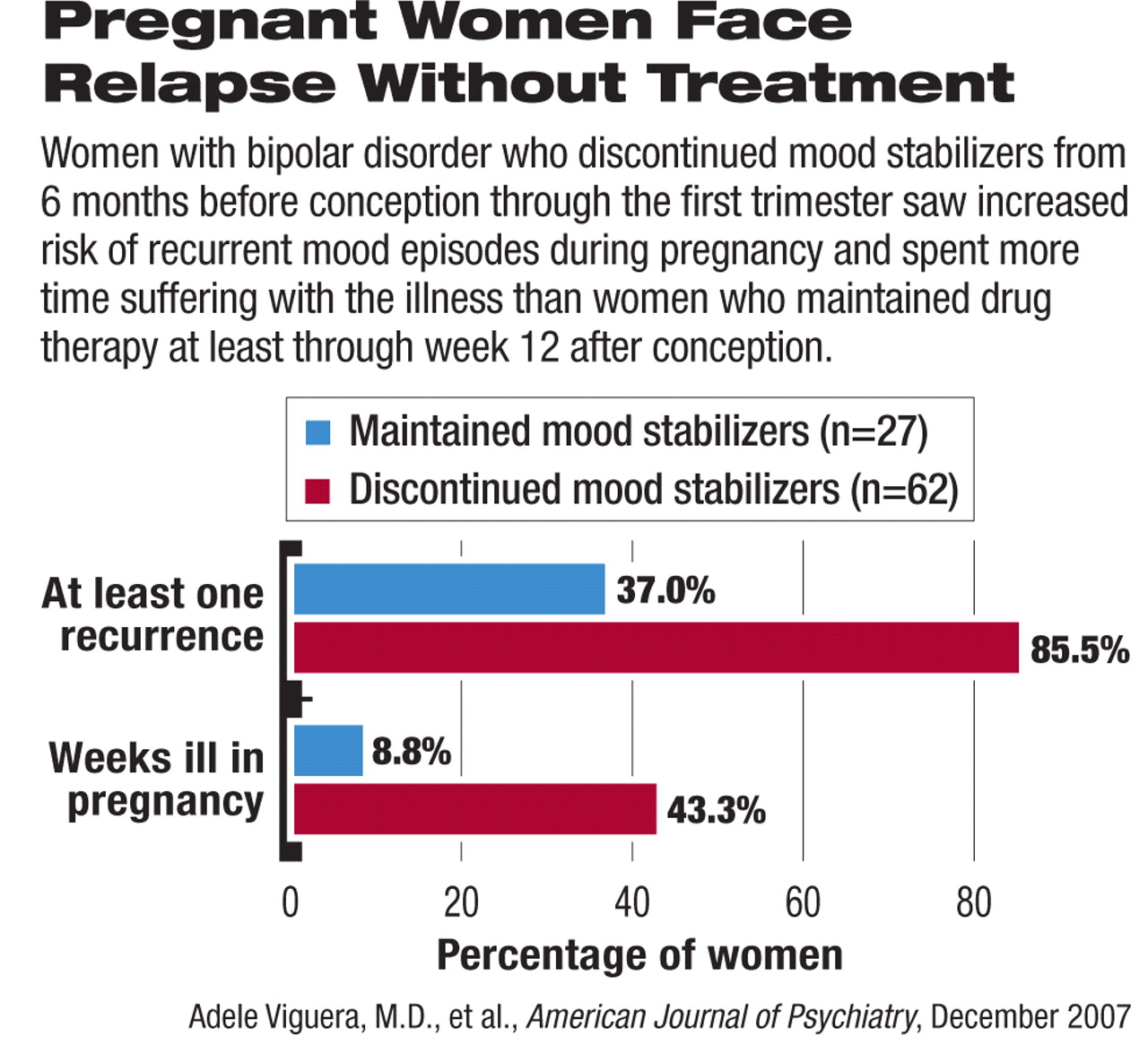

More than two-thirds of the enrolled women discontinued their drug therapy for bipolar disorder in the period between six months before and 12 weeks after conception, while 27 remained on the medications through at least 12 weeks after conception. Those who discontinued their bipolar medications within six months before through 12 weeks after conception were compared with women who continued taking mood stabilizers at least through 12 weeks after conception (see chart).

The women who discontinued their bipolar medications more than doubled their likelihood of suffering a recurrence of at least one episode of the illness (85.5 percent versus 37.0 percent) and spent over 40 percent of the time during pregnancy suffering bipolar symptoms, compared with only 8.8 percent of the time during pregnancy for those who maintained pharmacotherapy.

In addition, the women who abruptly stopped their mood stabilizers (within one to 14 days) had a 50 percent risk of recurrence within just two weeks. In contrast, a more gradual discontinuation (more than 15 days) reached the same risk in 22 weeks. This observation further emphasizes the danger of interruption to medication treatment.

The researchers also observed a “striking excess” of depressive or dysphoric mixed episodes, even among those with bipolar I disorder, while“ mania and hypomania were relatively infrequent.” They also noted in their report that the study results call into question previous suggestions that pregnancy may have some protective effect against new or worsening bipolar episodes.

The women in this study who maintained mood stabilizers during pregnancy were not necessarily more severely ill than those who discontinued the treatment, but they did skew toward having bipolar I disorder, taking lithium rather than an anticonvulsant, and having a history of psychotic features.“ Nearly 70 percent of women in the present study sample elected to discontinue mood-stabilizing treatment at the start of pregnancy, regardless of illness severity,” Viguera told Psychiatric News.“ Moreover, we found that most patients with an unplanned pregnancy stopped their mood stabilizer abruptly, which exacerbated their risk of recurrence with respect to becoming ill faster than women who tapered off treatment more slowly.”

Mood stabilizing medications do pose risks of birth defects. Lithium and divalproex are both pregnancy category D drugs according to the FDA's classification, as both carry risks of causing congenital abnormalities such as neural tube and cardiovascular defects.

The authors pointed out, however, that untreated relapses of bipolar episodes are also dangerous for the health of both the mother and the fetus.“ Maternal psychiatric illness, if inadequately treated or untreated, may be associated with poor compliance with prenatal care, inadequate nutrition, increased alcohol and tobacco use, disruption in maternalinfant attachment, and family stress. Data also suggest that children of depressed parents are at greater risk for behavioral and emotional difficulties,” Viguera noted.

She urged clinicians to provide the best information on the spectrum of risks associated with both pursuing and deferring treatment during pregnancy, including the risk of relapsed illness. Effective communication between the physician and the patient “affords clinicians the opportunity to make collaborative treatment decisions consistent with individual needs and wishes.” Like epilepsy and other illnesses with serious complications, bipolar disorder may require continued drug therapy during pregnancy for certain patients.

In an accompanying editorial, Marlene Freeman, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas South-western Medical Center, called this study “groundbreaking.” She urged clinicians to anticipate the complications of pregnancy in treating bipolar disorders and proactively discuss the risks and benefits with patients, since most female patients become ill before or during their reproductive years.

“Especially in the case of neural tube defects with the use of anticonvulsants, the window of greatest concern is very early in pregnancy,” said Freeman. “By the time a woman discovers she is pregnant, the most serious period of risk for the fetus has frequently already passed.” Rapid disruption of medication at this time therefore can pose more risks than protection.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, NARSAD, the Bruce J. Anderson Foundation, McLean Private Donors Psychopharmacology Research Fund, and Stanley Research Institute.

“Risk of Recurrence in Women With Bipolar Disorder During Pregnancy: Prospective Study of Mood Stabilizer Discontinuation” is posted at<ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/164/12/1817>; the editorial “Bipolar Disorder and Pregnancy: Risks Revealed” is posted at<ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/164/12/1771>.▪