Ever since Jack the Ripper terrorized young women in Victorian London, murders in England have captured the imagination of the public.

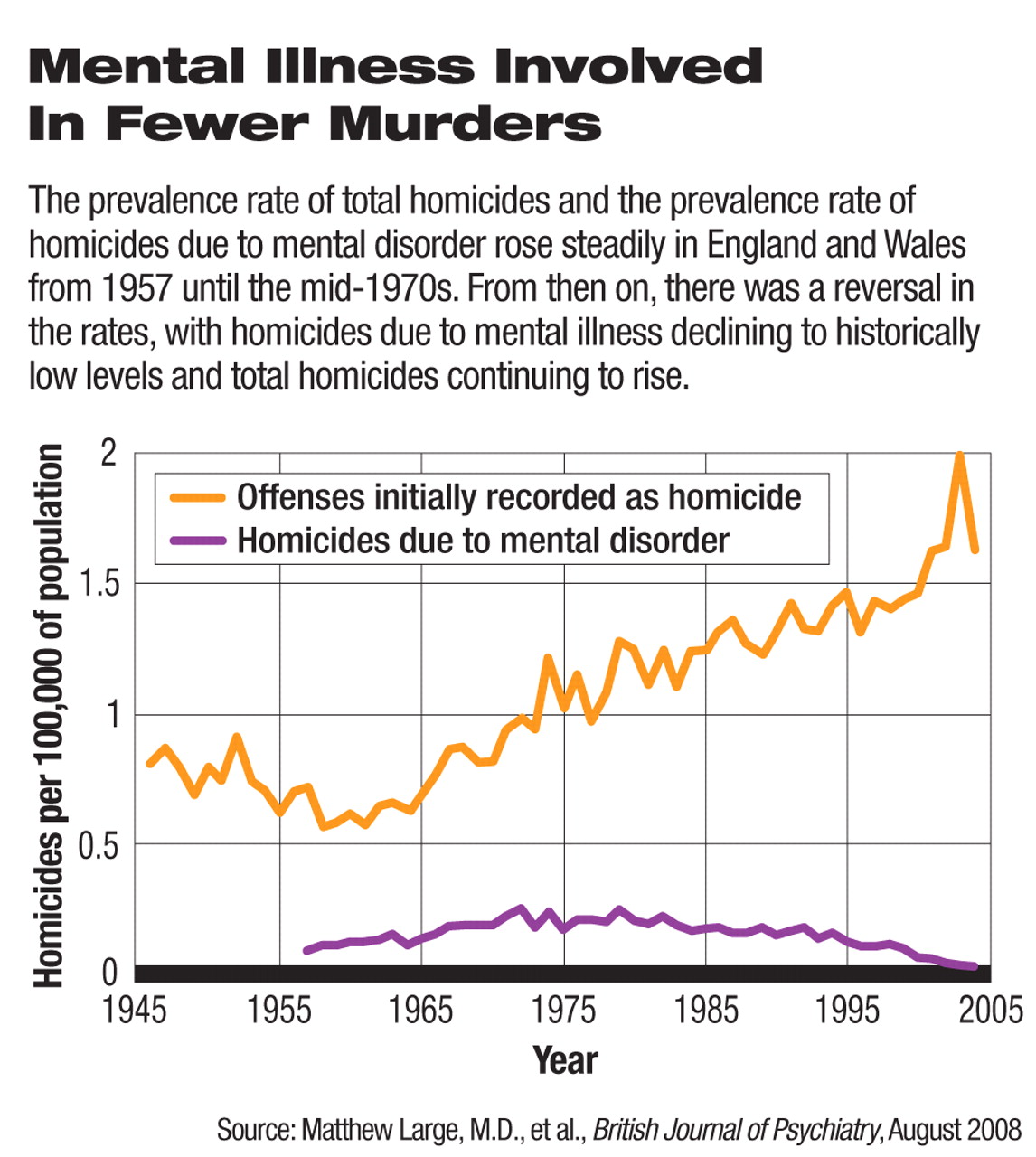

Yet good statistics on the annual prevalence rate of murders in England and Wales were not readily available before 1957. After that, they indicate that the annual prevalence rate of murders in England and Wales has risen until, by 2000, there were more than 1.5 homicide convictions per 100,000 population.

In contrast, the annual prevalence rate of murders by people with mental illness in England and Wales rose steadily from 1957 until the mid-1970s, but then declined.

These findings on homicide trends were published in the August British Journal of Psychiatry.

Have such trends also been documented in other countries? Apparently not to any great extent. The lead researcher of this study, Matthew Large, M.D., a psychiatrist in private practice in Sydney, Australia, told Psychiatric News, “There are no Australian data—hence my examination of United Kingdom data. There are also no United States data that I can find. There may well be some unpublished data from northern Europe, but I have not been able to access it.”

Just because such data aren't available, of course, doesn't rule out the possibility that homicides by people with mental illness have also been declining in countries other than England and Wales. And if there is a general international trend in this direction, what could be the explanation? Essentially that “treatment [of the seriously mentally ill] prevents homicide,” Large said.

In fact, a study headed by one of Large's collaborators, Jenny Shaw, Ph.D., and published in the November 2006 Psychiatric Services, suggests the same conclusion. Shaw and her colleagues found that of the 1,594 individuals convicted of homicide in England and Wales between 1996 and 1999, 85 (5 percent) had schizophrenia, and that out of these 85, only 43 (51 percent) had received any treatment for their illness during the year preceding their commission of murder.

Large and colleagues also conducted a study on this subject in New South Wales, Australia, he said, and there, too, they found that “most homicide offenders with psychosis had not been treated.” Those findings appeared in the May 2007 Medical Journal of Australia.

Of course, making sure that people with serious mental illness receive treatment can be a tall order in any country, Large admitted. However, meeting that challenge can be either impeded or eased by a country's legal requirements, he pointed out. For example, under Australian law, as under the law in many American states, treatment cannot be forced on seriously mentally ill people unless they are shown to be dangerous. This requirement“ makes no sense at all,” he said, since “predictions of dangerousness are very inaccurate, and prediction of homicide is not possible.” Yet the United Kingdom, in contrast, has no such legal requirement for proof of potential dangerousness, he said.

The study had no outside funding.