It is well known that people tend to feel happier and more energetic in the spring and summer when there are more hours of daylight, and to feel more gloomy and lethargic in the fall and winter when daylight hours are reduced. The nerve transmitter serotonin seems largely to explain such mood fluctuations: more of it is present in the brain in the spring and summer than in the fall and winter.

But why is more serotonin present in the brain in the spring and summer? One answer seems to have been found by Canadian and Austrian researchers: proteins called serotonin transporters, which deprive nerves of the“ feel good” nerve transmitter serotonin, are more plentiful in the brain during the fall and winter than during the spring and summer.

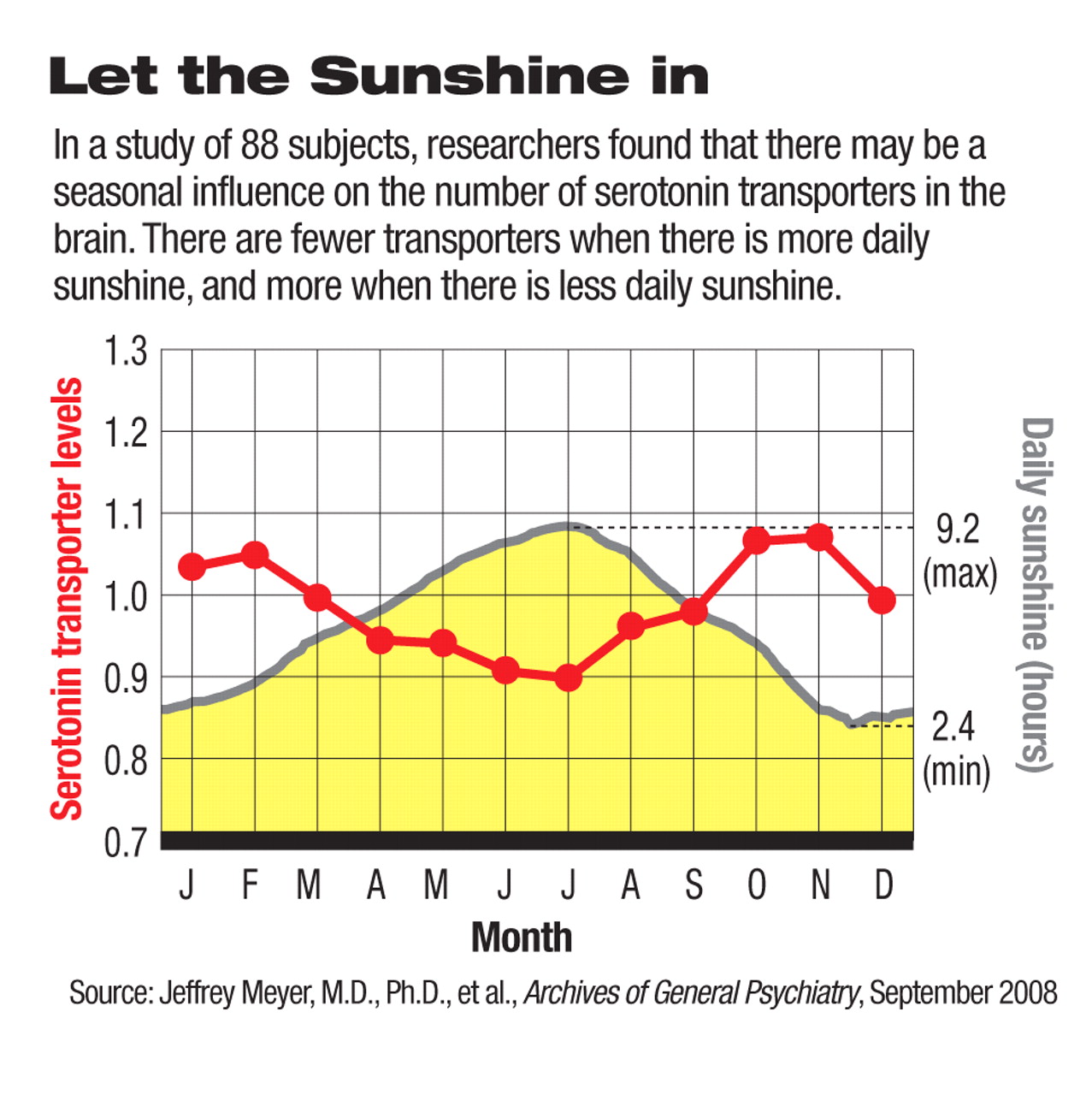

Jeffrey Meyer, M.D., Ph.D., head of neurochemical imaging in mood disorders at the Center for Addiction and Mental Health at the University of Toronto, and colleagues used PET scans to assess the number of serotonin transporters in the brains of 88 mentally and physically healthy subjects from 1999 through 2003. They found significantly more transporters in all parts of the subjects' brains in the fall and winter than in the spring and summer.

This is the first time, it appears, that such a seasonal change in brain physiology has been found in any species, Meyer told Psychiatric News. Moreover, “the robustness of the results was quite surprising.” Thus, there seems to be an inverse seasonal relationship between serotonin and serotonin transporters, and serotonin transporters may well serve as seasonal switches for serotonin and mood, Meyer and his colleagues concluded in the September Archives of General Psychiatry.

But if serotonin transporters act as seasonal switches for serotonin and mood, what controls the transporters? Sunlight, Meyer and his colleagues suspect, because they also found significant inverse links between the number of transporters in subjects' brains and the average duration of daily sunlight and day length. Yet other environmental factors might play a role as well, they believe. For example, their preliminary results also suggest that humidity is an influence, but that temperature is not. Indeed, their next goal, Meyer explained, will be “to understand in detail how environment influences serotonin transporters and then to develop strategies to interfere with this [influence] so as to minimize the adverse effects of seasonal change upon mood in people.”

Meyer and his team have also made another interesting discovery: the genetic composition of the gene that codes for the serotonin transporter influences the number of serotonin transporters in the brain, but not as much as sunlight duration does. So, one might tentatively conclude that sunlight duration has an even greater impact on mood than the genetic composition of the serotonin transporter gene does.

Finally, the findings raise some provocative questions—for instance, might the ebb in serotonin transporters that transpires in the spring contribute to the spring peak in suicides in the northern hemisphere? On the surface, the idea doesn't make much sense, they admitted, since fewer transporters should mean more available serotonin, and more available serotonin should mean a more elevated mood and more energy. But animal research, they pointed out, has shown that a short-term depletion of serotonin transporters in one area of the brain can temporarily reduce the amount of serotonin available in other brain areas. Such a temporary imbalance, they speculated, might explain why suicides tend to peak in the spring.

The study was funded by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the Austrian Science Foundation, the Canadian Institute for Health Research, the Ontario Mental Health Foundation, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and the Ontario Innovation Trust.