Projections that mental health care spending, including that for substance use, will increase as part of cost increases in overall health care have raised concerns among some leaders in psychiatry that eventual cost-cutting could target mental health.

Their concern is that ongoing increases in overall health care spending are increasing the pressure on government and private-sector leaders to cut costs, which may disproportionately impact mental health and addiction services.

Steven Sharfstein, M.D., president and CEO of Sheppard Pratt Health System in Baltimore and a former APA president, said that recent research added to his concern that the long-term trend of continued growth in health care spending remains far beyond the national inflation rate. When health care spending as a portion of gross domestic product begins to reach 25 percent to 30 percent, he said, something has to give. The seemingly inevitable cost-cutting that will be needed to curtail that future growth will hit mental health and substance use at least as hard as the rest of health care.

“Let's hope that mental health and substance abuse funding does not face a disproportionate burden of cost cutting,” Sharfstein said.“ History tells us, however, that we will be hit hard.”

His concerns came in response to recent findings that spending on mental health and substance abuse treatment is expected to double to $239 billion annually from 2003 to 2014, while overall health cost growth, including mental health care, is expected to rise from $2 trillion to $3.5 trillion annually in the same time frame. The estimates came from federal research published online in Health Affairs in October.

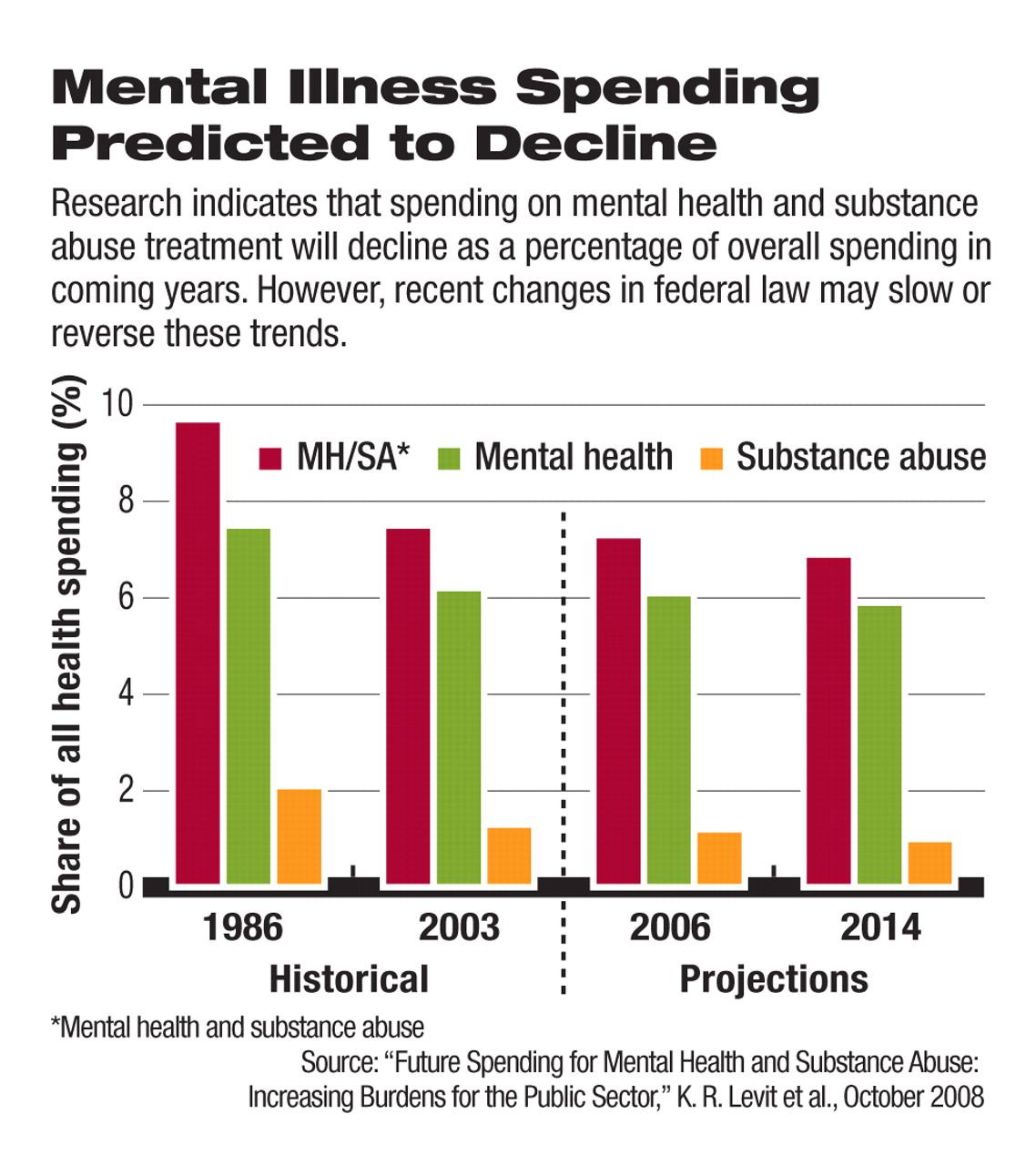

The researchers, including Jeffrey Buck of the Center for Mental Health Services at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), concluded that the projected growth in mental health and substance use treatment spending would likely fall from 7.3 percent to 6.9 percent of all health care spending because of the expected ballooning of the cost of health care overall.

“Unlike most of the health care sector, [mental health and substance use] treatment does not rely extensively on high-priced, rapidly evolving technology (other than prescription medications), which drives overall health cost increases,” wrote Buck and colleagues, about the reason mental health spending is likely to fall as a percentage of overall health care spending.

The findings were based on population-growth and inflation projections and earlier SAMHSA data on the extent of spending on each category of care.

Psychiatry Leaders Disagree

The research likely underestimates future spending on mental health and addiction care services, according to some critics. That projection of future psychiatric illness spending also underestimates its role as a future budget-savings device.

Sharfstein said the research predated the recent passage of the federal mental health parity legislation in October (see

Parity Law's Next Hurdle: Working Out Fine Print) and a reduction in the Medicare copay for outpatient mental health services to the level required for all other types of care. Both changes are likely to boost use of mental health and substance use care, which would increase the amount spent on those services.

Enactment of the parity law could lead to more private insurance funding for treatment of mental illness, including substance abuse, Sharfstein said (Psychiatric News, October 17).

Laurence Miller, M.D., chair of APA's Committee on Public Funding for Psychiatric Services, agreed that both the insurance parity law and the copay change to Medicare—enacted in July—would likely increase use of these services (Psychiatric News, August 1).

“With parity, there will be a little less stigma, so people will be more willing to use” mental health services, Miller told Psychiatric News.

The recent sharp downturn in the nation's economy also could affect demand and spending on these services, because laid-off workers facing multiple, unexpected crises in their lives may develop mental illnesses or substance use problems in higher numbers than when the nation's economy was thriving.

The economic downturn “could also lead to more, not less, public financing,” Sharfstein said.

Most state Medicaid programs are expected to face budget shortfalls next year, as the nation's economy stalls and demand for public health care assistance continues to rise, according to an annual survey of state program directors. To counteract this, congressional Democrats have been planning a post-election lame-duck session to try to pass a temporary boost to states for Medicaid programs as part of a second economic stimulus package to fend off further economic erosion. Congress approved a $20 billion state Medicaid program assistance package during the 2002 recession in the form of an increased Medicaid match and general grants to states.

Limiting Future Cuts

The possibility of curtailing overall health care spending growth on the backs of mental health and substance use budgets may be reduced by the increasing need that the general public sees for such care.

One development that could increase utilization of mental health services is the increasing numbers of veterans seeking care for combat-related mental illness. The issue could directly impact Medicaid and private insurers as many returning veterans are either members of the National Guard and ineligible for care from the Department of Veterans Affairs or they are trying to hide their conditions by seeking care outside the military, said Miller.

Increasing demand for mental health care among the general population may run into the problem of shrinking access, as psychiatrists opt out of underpaying health care programs.

A growing number of psychiatrists no longer accept Medicare, Medicaid, or even private insurance, so the increasing number of patients seeking care as the stigma of mental illness declines could meet a lack of clinicians to provide that treatment, according to Miller.

A survey of psychiatrists published in the April 2005 Psychiatric Services found that although a substantial proportion of psychiatrists (77 percent) accepted patients who used “self-pay,” less than half (44 percent) accepted patients whose care was paid by Medicaid. Additionally, only 63 percent of psychiatrists said they accepted new Medicare patients, a significantly higher percentage than those who accepted patients in either private managed insurance plans or Medicaid, according to the survey based on a national sample of 2,323 U.S. psychiatrists.