Psychotropic medications were prescribed two to three times more often to American children and adolescents than to their peers in the Netherlands or Germany, according to a study by investigators from all three countries. The study was based on data from the year 2000.

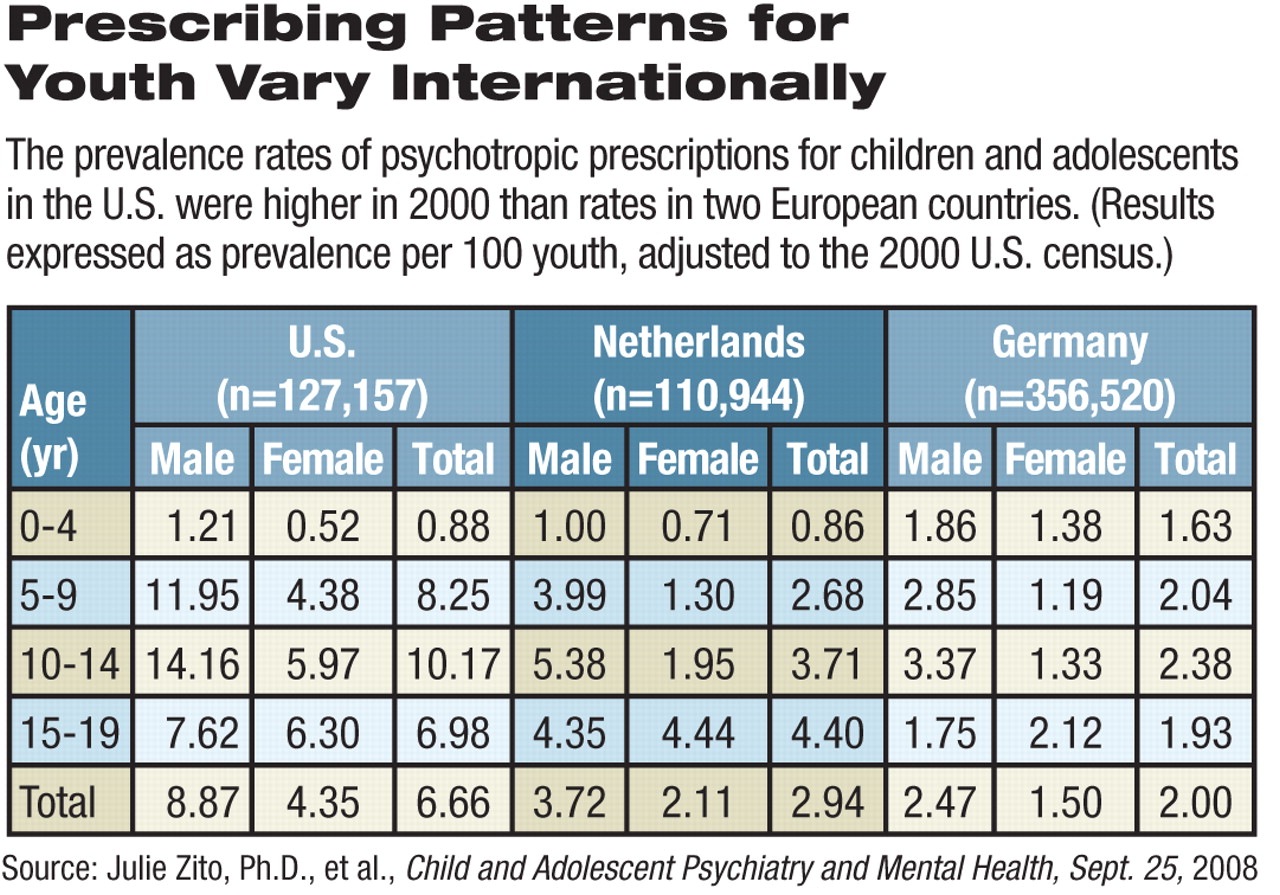

“The annual prevalence of any psychotropic medication in youth was significantly greater in the United States (6.7 percent) than in the Netherlands (2.9 percent) and in Germany (2.0 percent),” wrote Julie Zito, Ph.D., of the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy and seven colleagues who posted their findings September 25 in the open-access online journal Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health.

About 19.2 percent of U.S. youth taking these medications were prescribed more than one drug, twice the rate in the Netherlands and three times that in Germany, they said.

The researchers used administrative claims data from 2000 to look at prescribing patterns. Data covered children up to age 19: 110,944 in the Netherlands, 356,520 in Germany, and 127,157 in the United States, the last drawn from enrollees in the State Children's Health Insurance Program. Classes of drugs included antidepressants, antipsychotics, alpha-agonists, anxiolytics, hypnotics, lithium, and antiparkinsonian agents. Prevalence was defined as dispensing one or more prescriptions for those classes of medications per 100 youth.

Zito and colleagues suggested several reasons for the differences, starting with culture.

“U.S. medical treatment is more interventionist and activist across the board,” said Zito in an interview. In the study, more than half (51.7 percent) of the patients prescribed these medications in the United States were under age 5, compared with 24.7 percent in the Netherlands and 21 percent in Germany. The authors used statistical methods to adjust the disparity caused by the U.S. data to the age distribution found in the 2000 census.

Lithium, antiparkinsonian agents, anxiolytics, and antipsychotics were used by less than 1 percent of youth in all three countries. However, among patients prescribed antipsychotics, just 5 percent of German children were prescribed atypical antipsychotics, compared with 48 percent in the Netherlands and 66 percent in the United States.

“Furthermore, among 0-4 year-olds, German youth had the highest antipsychotic prevalence (0.64 percent), followed by the Netherlands (0.10 percent), and the United States (0.07 percent), a stark reversal of the leading usage trends observed in other drug classes, [such as] antidepressants and stimulants,” wrote the authors.

Prevalence of stimulant prescriptions across the entire age range was 4.3 percent in the United States, 1.2 percent in the Netherlands, and 0.7 percent in Germany.

Overall antidepressant prevalence was 2.7 percent in the United States, 0.5 percent in the Netherlands, and 0.2 percent in Germany. Within this class, 15 percent of U.S. youth received tricyclic antidepressants, compared with 48 percent in the Netherlands and 73 percent in Germany.

There may be a number of reasons for the differences in prescribing patterns among the three countries, said Zito. For one, in Europe, regulations limit or prohibit prescription of amphetamines, and cost restrictions limit use of many expensive, on-patent drugs.

The use of the International Classification of Diseases-10 rather than DSM-IV as a standard in Europe may also affect diagnoses and treatment choices. Specialists such as pediatricians and psychiatrists prescribe these drugs more often in the United States, while in Europe general practitioners prescribe most psychotropics.

Higher rates of prescribing more than one medication may represent more than a quick reach for the prescription pad in the United States, said Zito.

“It may be because the response of children in the community to drugs is not as high as among the carefully selected clinical trials cohorts,” she said. In those cases, a second drug may be added.

But children also need a comprehensive treatment plan, one involving the whole family and not focused on the child alone.

“Sending a child home on five medications after four days in the hospital can only lead to bad outcomes and wasted treatment opportunities,” she said. “Maybe we could invest more in behavioral training of children.”

Her study should be viewed as a starting point for further research that will follow cohorts of children over longer periods, not merely assess the efficacy of a drug over a few weeks, she added.

“A Three-Country Comparison of Psychotropic Medication Prevalence in Youth” is posted at<www.capmh.com/content/pdf/1753-2000-2-26.pdf>.▪