During the past few years, the brain hormone oxytocin has received quite a bit of attention in the popular press. For instance, an article in the New York Times reported that “the compound can spur an overwhelming urge to cuddle,” and “in some cases, it works as an aphrodisiac....” An article in New Scientist reported that oxytocin “peaks with orgasm, makes a loving touch magically melt away stress....”

Moreover, oxytocin perfume is even being sold to the public over the Internet. Whether it is worth the hype that it's getting is unclear. One oxytocin researcher—David Feifel, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego—is unconvinced, and another oxytocin scientist—Markus Heinrichs, Ph.D., a professor of clinical psychology and psychobiology at the University of Zurich in Switzerland—agreed: “There is no reason to believe that oxytocin on the skin or clothes should significantly change behavior.” But one thing is for sure: oxytocin does indeed have some provocative properties, animal and clinical research is showing.

True, oxytocin has long been known to be crucial for labor prior to the birth of a baby and for the breast feeding that comes after a baby is born. But in recent years it has also been found to enhance social interactions and the formation of attachments in both experimental animals and humans. And during the past decade, the means whereby oxytocin acts as a social catalyst have become increasingly evident.

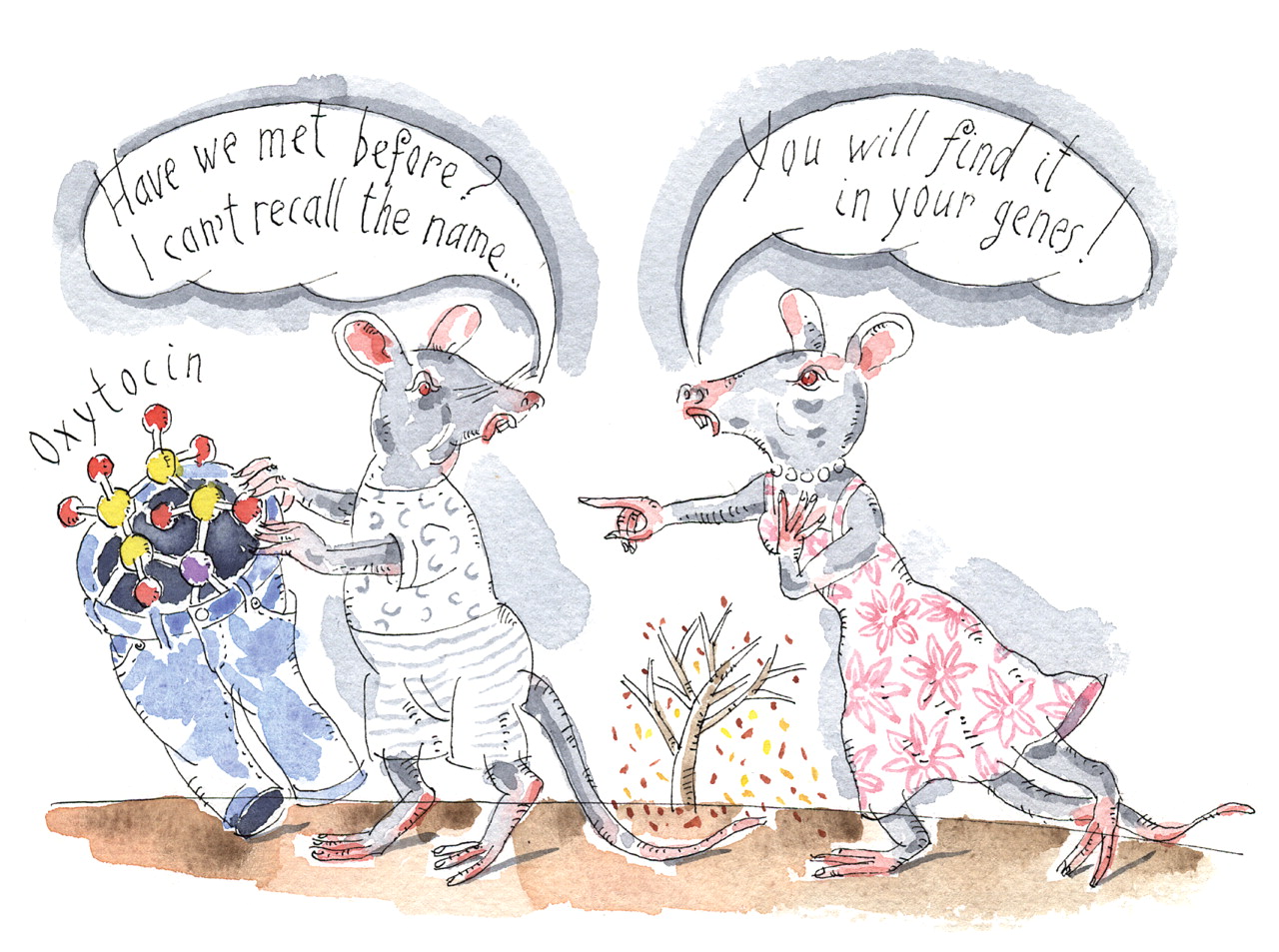

For example, oxytocin seems to promote social interactions by promoting social recognition. Thomas Insel, M.D., director of the National Institute of Mental Health, and colleagues reported in the July 2000 Nature Genetics that mice lacking the gene for oxytocin experienced social amnesia—that is, they failed to recognize mice they had already met (Psychiatric News, July 2, 2004).

Oxytocin also seems to promote social interactions by increasing people's trust in others. Michael Kosfeld, Ph.D., of the Center for the Study of Social and Neural Systems at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, along with other researchers, reported in the June 2, 2005, Nature that male subjects who inhaled a nasal spray spiked with oxytocin gave more money in a risky investment game than did male subjects who sniffed a spray containing no oxytocin.

Still other ways in which oxytocin works as a social catalyst appear to be by helping people intuit the mental state of others, increasing a person's gaze toward the eye region of another person, and getting a person to remember positive rather than negative encounters with another person. These results, from Gregor Domes, Ph.D., of Rostock University in Germany, and colleagues and from Adam Guastella, Ph.D., of the University of New South Wales in Australia, and colleagues were published in the March 15, 2007, January 1, 2008, and August 1, 2008, issues of Biological Psychiatry.

But perhaps the most critical means whereby oxytocin brings people together is by reducing anxiety, experts suggest.

A Little Romance, a Lot of Oxytocin

Donatella Marazziti, M.D., a psychiatrist at the University of Pisa in Italy, reported in the October 2006 Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health a significant link between blood levels of oxytocin and anxiety over romantic attachment in human subjects—that is, the greater the anxiety, the higher the oxytocin levels. Since animal research has shown that oxytocin has antianxiety properties, it's quite possible that people in the throes of romance produce a surplus of oxytocin to quell their anxiety, Marazziti told Psychiatric News.

And the means by which oxytocin dampens anxiety may be by cooling the amygdala, the brain's fear center, Andrews Meyer-Lindenberg, M.D., Ph.D., of the National Institute of Mental Health and colleagues reported in the December 7, 2005, Journal of Neuroscience. Thomas Baumgartner, Ph.D., of the Center for the Study of Social and Neural Systems at the University of Zurich in Switzerland, and his colleagues reported similar findings in the May 22 Neuron.

It Has Antianxiety-Drug Potential

Not surprisingly, such findings are stimulating efforts to see whether oxytocin might work as an antianxiety medication.

For example, Pradeep Nathan, Ph.D., of the University of Cambridge in England, and his colleagues are undertaking a trial to find out whether intranasally delivered oxytocin can attenuate fear in subjects with social anxiety disorder. “We should have some data by July 2009,” he told Psychiatric News.

Heinrichs and coworkers are conducting a clinical trial to see whether oxytocin can help people with generalized anxiety disorder. “We expect data early in 2009,” he said. They are also conducting a trial to see whether oxytocin combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy might also benefit such individuals, he added.

Robert Ring, Ph.D., head of molecular neurobiology at Wyeth Research in Princeton, N.J., and coworkers have found that an oxytocin receptor agonist called WAY-267464 produces, in experimental animals, antianxiety effects similar to those produced by oxytocin itself.

Oxytocin also looks promising as a new type of treatment for the social deficits experienced by persons with autism spectrum disorders. Eric Hollander, M.D., chair of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City, and colleagues tested the ability of 15 adults with an autism spectrum disorder to detect the emotional intonations of sentences—expressing, say, anger, sadness, or happiness—a task in which they typically have difficulty. The researchers then gave the subjects intravenous infusions of a placebo or infusions of oxytocin and repeated the tests. Finally, the researchers compared the before-and-after results under both the oxytocin and placebo conditions.

The subjects improved their ability to detect emotions in speech under both conditions. However, their ability was more enduring under the influence of oxytocin. “These results are consistent with studies linking oxytocin to social recognition in rodents as well as studies linking oxytocin to prosocial behavior in humans and suggest that oxytocin might facilitate social-information processing in those with autism,” Hollander and his team concluded in the February 15, 2007, Biological Psychiatry.“ These findings also provide preliminary support for the use of oxytocin in the treatment of autism.”

In fact, Hollander and his group are now conducting a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to explore the long-term therapeutic benefits of oxytocin in autism subjects. Also, this time oxytocin will be given intranasally instead of by injection.

It's even possible that oxytocin might enhance social behavior in individuals with schizophrenia. David Feifel, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and coworkers are recruiting subjects for a clinical trial to test the value of oxytocin as an add-on treatment for schizophrenia.

Oxytocin's Therapeutic Future

So, what is oxytocin's future as an antianxiety, social-promoting medication? Is it possible that it might become clinically available within the next decade to treat persons who are anxious and/or socially impaired—say, those with social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, autism, or schizophrenia?

“Following appropriate clinical trials, yes,” Hollander told Psychiatric News.

Feifel thinks so too, although “it may not be oxytocin, but a proprietary analog” that receives Food and Drug Administration approval, he said.

On the whole, the oxytocin story “is a great story,” Ring said.“ We are all excited by the recent increase in reports from small clinical studies investigating the effects of synthetic oxytocin on central nervous system function in human subjects,... [and] I think it may go somewhere.”

But unfortunately, he added, the oxytocin receptor agonist WAY-267464“ does not have any of the attributes that you would look for in a clinical [drug] candidate,... and it is important for the field to appreciate the practical limitations of using synthetic oxytocin as an actual treatment approach for chronic central nervous system disorders.”

For example, when synthetic oxytocin is delivered orally, only a small amount reaches the brain, and when it is given intranasally, it has only short-term effects. Actually, a biotechnology firm located in Bothell, Wash.—MDRNA Inc.—was planning to try to create a long-acting inhaled form of synthetic oxytocin, but then it shelved this program, Matthew Haines, senior director of corporate communications for MDRNA, told Psychiatric News. “We have changed our focus as a company from the intranasal delivery of proteins and peptides to the development of RNA-interference therapeutics,” Haines explained

Nonetheless, MDRNA's program to develop a long-lasting intranasal form of synthetic oxytocin is “available for outlicensing,” Haines added.▪