The U.S. Army hopes to encourage more soldiers to seek care for mental health problems by expanding a program to detect and treat soldiers with depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in primary care clinics, backed up by consultations with psychiatrists.

The staged rollout of the program, known as RESPECT-Mil, began one year ago at the direction of the Army surgeon general and will spread to 43 clinics on 15 military bases in the U.S., Germany, and Italy over 24 months. Program leaders from 13 of the 15 bases have been trained in its function so far, and about 10 clinics have it in operation. Congress recently increased funding to expand the program further.

The service hopes to undercut the effects of stigma by providing an entry point and screening for soldiers in a setting they find more comfortable.

Many troops and officers worry about disclosing depression, anxiety, or other symptoms resulting from the stresses of deployment or combat, despite attempts to address mental health more openly.

“Some patients fear the effects on their careers of coming into direct contact with a mental health professional, but they will see a primary care provider,” said Col. Charles Engel, M.D., M.P.H., in a talk to the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies in November 2007.

RESPECT-Mil is the military version of the “Re-Engineering Systems for Primary Care Treatment of Depression,” a model developed over the last decade by researchers from Dart mouth Medical School, Duke University Medical Center, and others, backed by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation's Initiative on Depression and Primary Care. The model uses three types of providers: care managers, primary care providers, and psychiatrists.

The original MacArthur program began in 1995 at the behest of primary care providers led by Allen Dietrich, M.D., a family medicine specialist at Dartmouth, now a consultant to the Army.

“The MacArthur initiative was intentionally designed not to be a research trial,” said Thomas Oxman, M.D., professor emeritus of psychiatry at Dartmouth and also a consultant to the Army's project, in an interview with Psychiatric News. “We were interested in dissemination and permanence from the start, and we wanted users to incur minimal costs.”

To cut costs in the MacArthur initiative, for instance, telephone monitoring was used instead of face-to-face sessions with patients, and the care managers were not required to have medical or mental health backgrounds, just good interpersonal skills.

RESPECT-Mil tries to address barriers to care for both soldiers and providers. Primary care providers needed more help recognizing and treating these conditions, protocols had to be in place and understood, long-term follow-up and support for patients were needed, and primary care clinicians and psychiatrists had to improve coordination.

Preparation for RESPECT-Mil begins by training the three sets of professionals involved. The Army decided to use only nurses as care managers and calls them facilitators. The facilitators get four to eight hours of specialized training, while primary care providers (physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners) get two hours, and psychiatrists get one hour. Manuals delineate procedures for everyone.

Oxman has helped train Army personnel in the program. Once trained, they go back to their bases and train more staff. The program includes provisions for“ booster” training sessions, drawing on the clinical experience of the participants or case presentations. The biggest difference between civilian and military versions of the program are the current shortage of health care providers in the Army and the constant need to train new providers when the original ones get assigned to Iraq or Afghanistan, said Oxman.

Part of the delay in rolling out the program has come from the need to hire civilian nurses to serve as facilitators, said Engel, in a later interview. The civilians offer a stability and continuity of care that are often precluded by the frequent transfers of uniformed Army nurses.

Providers Have Change of Heart

“Some providers initially saw the program as more bureaucracy imposed on busy primary care clinics,” said Engel. “But when they see the body of research behind it and how many of the questions they raise have been thought through, they come to see its value.”

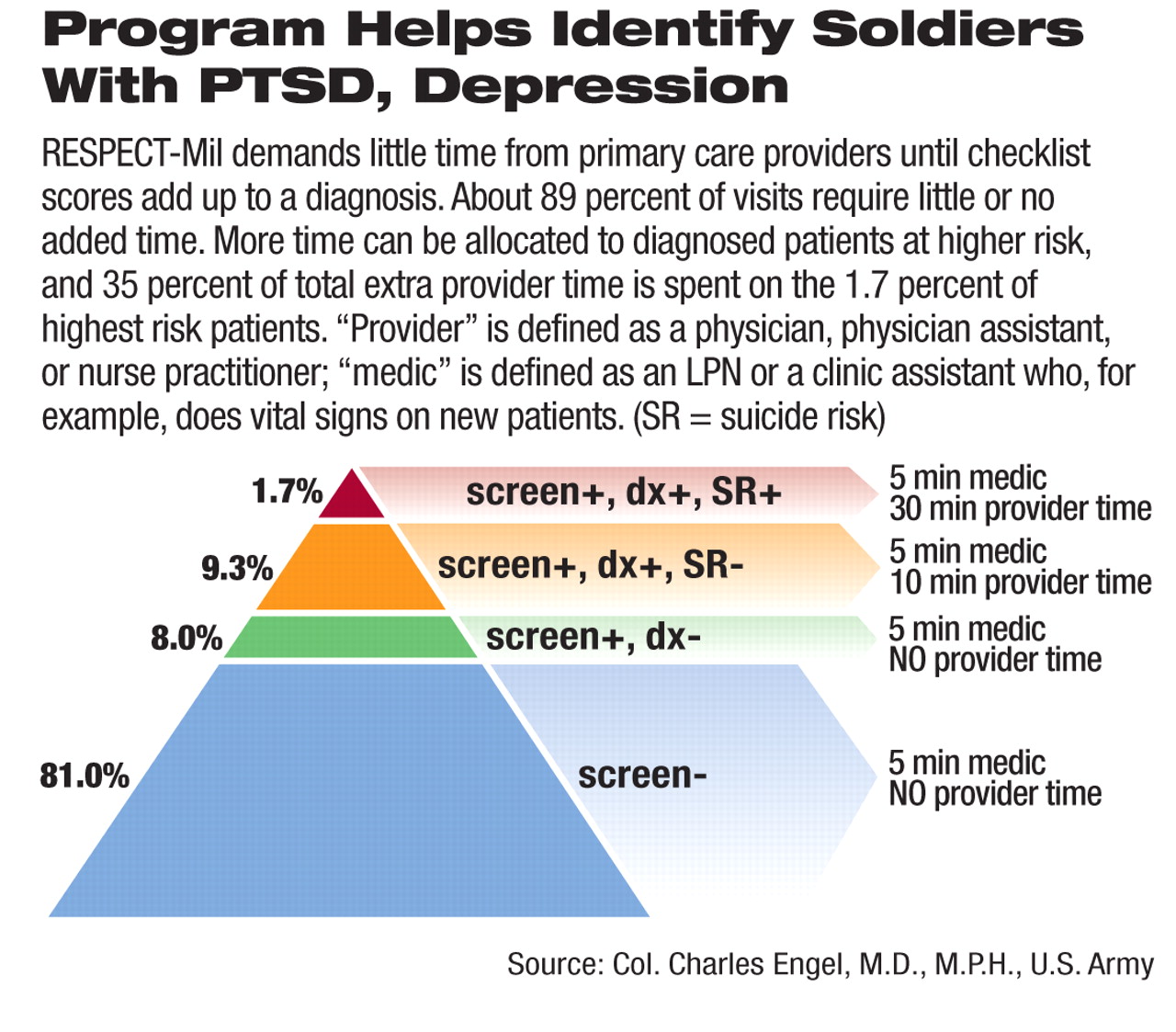

The system integrates the efforts of all three groups. During each visit, a medic administers a two-question depression screen (PHQ-2) and a four-item PTSD screen, said Engel. Anyone screening positive gets the full PTSD Check List and the full PHQ-9 for depression, plus a 10-minute session with the primary provider. The PHQ-9 score determines the provisional diagnosis and appropriate treatment recommendations. Any diagnosis of depression or PTSD also calls for an evaluation of suicide risk assessing suicidal thoughts and risk factors. Indications of suicidality call for a longer visit (30 to 45 minutes) with the provider.

Patients and providers discuss treatment options, including the risks and benefits of antidepressants. Patients may choose to accept medication or psychotherapy or both. (In earlier tests at Fort Bragg, N.C., about 10 percent of soldiers refused any treatment.) Soldiers also learn about other options for care, such as chaplains, Army Community Services, or Military OneSource, a contract service that provides support and counseling for troops and their families.

Psychiatrists Consult Weekly

The nurse facilitator takes over after the initial visit and follows each patient with telephone calls to monitor progress and offer support and suggestions. The psychiatrist consults weekly with the facilitator, who relays information back to the primary care provider.

Psychiatrists, although first concerned about the added workload (about 30 cases), are able to confer efficiently with the facilitators.

“Supervision requires about two to five minutes per patient, depending on patient acuity, severity, and past history of problems,” said Engel. “Many patients don't need any changes in treatment plan or have major risk factors, so these patients can be reviewed briefly.”

Those with significant problems need more time but are also more likely to be referred to specialty care and out of the primary care caseload. Patients remaining in primary care have less acute or severe symptoms and so require less time.

Initial response to treatment is evaluated at six to eight weeks for antidepressants and four to six weeks for psychological counseling; treatment is adjusted after that evaluation.

“We encourage adherence, overcome barriers, and monitor the response with accountable, continuous follow-up until remission,” said Engel, who is also director of the Deployment Health Clinical Center at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

It is too early to measure clinical outcomes of the program, but 75 percent of visits at participating sites have resulted in screens, compared with 2 percent to 5 percent at comparable sites. About 9 percent of the screens were positive for PTSD, 9 percent for depression, and 10 percent for both, said Engel. Furthermore, 91 percent of positive screens have documented referrals for follow-up visits.

“I feel like we're bringing people with unmet needs into the system,” said Engel. “The whole program is born out of a desire to reach out to soldiers.”

Information about RESPECT-Mil is posted at<www.pdhealth.mil/respect-mil.asp>.▪