People with an anxious form of depression are not as likely to respond to antidepressants and may be more sensitive to medication side effects than people with depression who don't experience the anxiety symptoms, according to a new report (for a different opinion see

Anxiety in Depression: Findings Questioned).

The study's researchers said that clinicians should be sure to include questions about anxiety on depression-screening instruments so they better know what to expect during treatment.

In a report in the March American Journal of Psychiatry, lead author Mauricio Fava, M.D., noted that the presence of anxiety symptoms in patients with depression is likely to complicate treatment.

Such symptoms “would indicate to us that we need to be more attentive to the management of medication side effects and the potential for patients dropping out of treatment,” he told Psychiatric News.

It may be advisable for clinicians to schedule office visits more closely together for patients with what Fava and his coauthors termed “anxious depression,” so that treatment progress can be more closely monitored.

The report defines anxious depression as major depressive disorder with high levels of anxiety symptoms indicated by a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) anxiety/somatization score of 7 or higher.

Fava is vice chair of psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital.

To obtain their results, Fava and his colleagues analyzed data from adult outpatients with major depressive disorder enrolled at 18 primary care and 23 specialty care settings across the United States as part of the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) Study.

To be eligible for the study, patients had to be between ages 18 and 75 and meet DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder, with a score of 14 or higher on the HAM-D.

Researchers obtained data on 2,876 patients who completed at least one visit after baseline measurements in level 1 of the study. In level 1, patients were treated with citalopram with the goal of achieving symptom remission, which was defined as having a score of 5 or less on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology.

Dose adjustments were guided by manualized treatment protocols that allowed for individualized starting doses and adjustments to minimize side effects. The protocol recommended treatment visits at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 6, 9, and 12, with an optional visit at week 14 if necessary.

Those who did not achieve symptom remission were encouraged to enter level 2 of the study, in which 1,292 patients were randomized to switch to sustained-release bupropion (n=239), sertraline (n=238), or extended-release venlafaxine (n=250). The rest of the patients continued taking citalopram with sustained-release bupropion (n=279) or buspirone (n=286). This trial also lasted up to 14 weeks.

The authors noted that anxious depression tended to be more common among minorities and those who were unemployed and had public insurance, lower levels of education, and lower income than those without anxious depression.

Patients with more severe depression at baseline, greater perceived physical impairment, more diminished quality of life, and later onset of major depression were also more likely to have anxious depression.

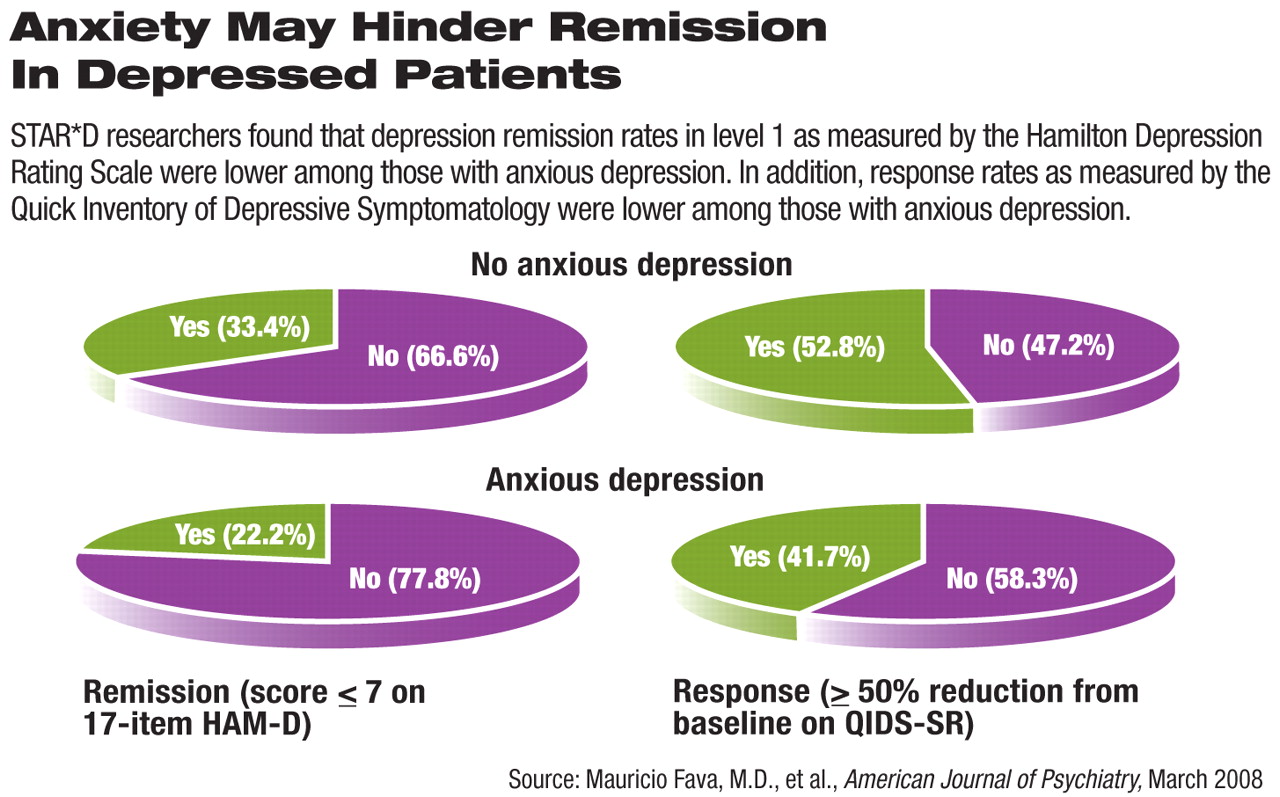

For level 1 subjects, Fava found that remission rates were significantly lower in patients with anxious depression as measured by HAM-D scores: 22.2 percent of patients with anxious depression experienced remission of symptoms, while 33.4 percent of those with nonanxious depression did.

Fava also analyzed data from a self-report version of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-SR) for both groups enrolled in level 1. He found a similar pattern, with 27.5 percent of those with anxious depression showing symptom remission and 38.9 percent of those with nonanxious depression showing remission.

Response rates, defined as 50 percent or greater reduction from baseline scores on the QIDS-SR, were also lower in patients with anxious depression (41.7 percent) than in those with nonanxious depression (52.8 percent).

The findings also showed that despite having similar citalopram dosages, patients with anxious depression experienced greater frequency, intensity, and burden of side effects and adverse events (including death, suicidal ideation, substance abuse, and psychiatric hospitalization) than those with nonanxious depression (p<.0001).

In addition, the number of hospitalizations for general medical conditions was higher for those with anxious depression during the study than it was for those without anxious depression (40 versus 18, respectively).

Level 2 participants with anxious depression, according to the report,“ fared significantly worse in both the switching and augmentation options.”

The authors noted that since there was not a placebo control group, it was impossible to determine whether patients with anxious depression were less responsive to true drug effects or less responsive to certain nonspecific aspects of treatment.

Also, the report highlighted the fact that patients with anxious depression had a higher physical illness burden, lower socioeconomic status, and greater severity of depression, factors that alone could have contributed to poorer outcomes.

“In general, these patients may be tougher to treat,” Fava commented. “We're not sure exactly why.”

He suggested that patients with anxious depression may need more aggressive treatment, which may include closer monitoring of symptoms and side effects. He said more research is needed to understand what specific treatments will be effective for patients with anxious depression.