“Financial exploitation is one of the major aspects of elder abuse in our society,” Daniel Marson, J.D., Ph.D., declared in a recent interview with Psychiatric News. “It is really a rampant problem. You read about it in the newspapers, but that is really like the tip of the iceberg.” Moreover, older people with Alzheimer's disease may be especially vulnerable to such exploitation, he said.

Marson should know. As a lawyer, a professor of neurology at the University of Alabama, and director of the university's Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, he often serves as an expert witness in such cases.

However, even older people who are in the early mild stages of Alzheimer's disease may be at particularly high risk of consumer scams, a study conducted by Marson and his colleagues suggests.

“Financial capacity is already substantially impaired in patients with mild Alzheimer's at baseline and undergoes rapid additional decline over one year,” Marson and his team concluded in their report, which appeared in the March American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

The results have implications for psychiatrists who diagnose and treat Alzheimer's patients, Marson believes. “At the time a psychiatrist diagnoses a patient with mild Alzheimer's disease, he or she should really impress upon the patient's family the importance of immediately securing financial affairs, estate plans, durable powers of attorney, and such. Also, he or she should alert the patient's family that the patient may be especially vulnerable to scams and other types of consumer fraud.”

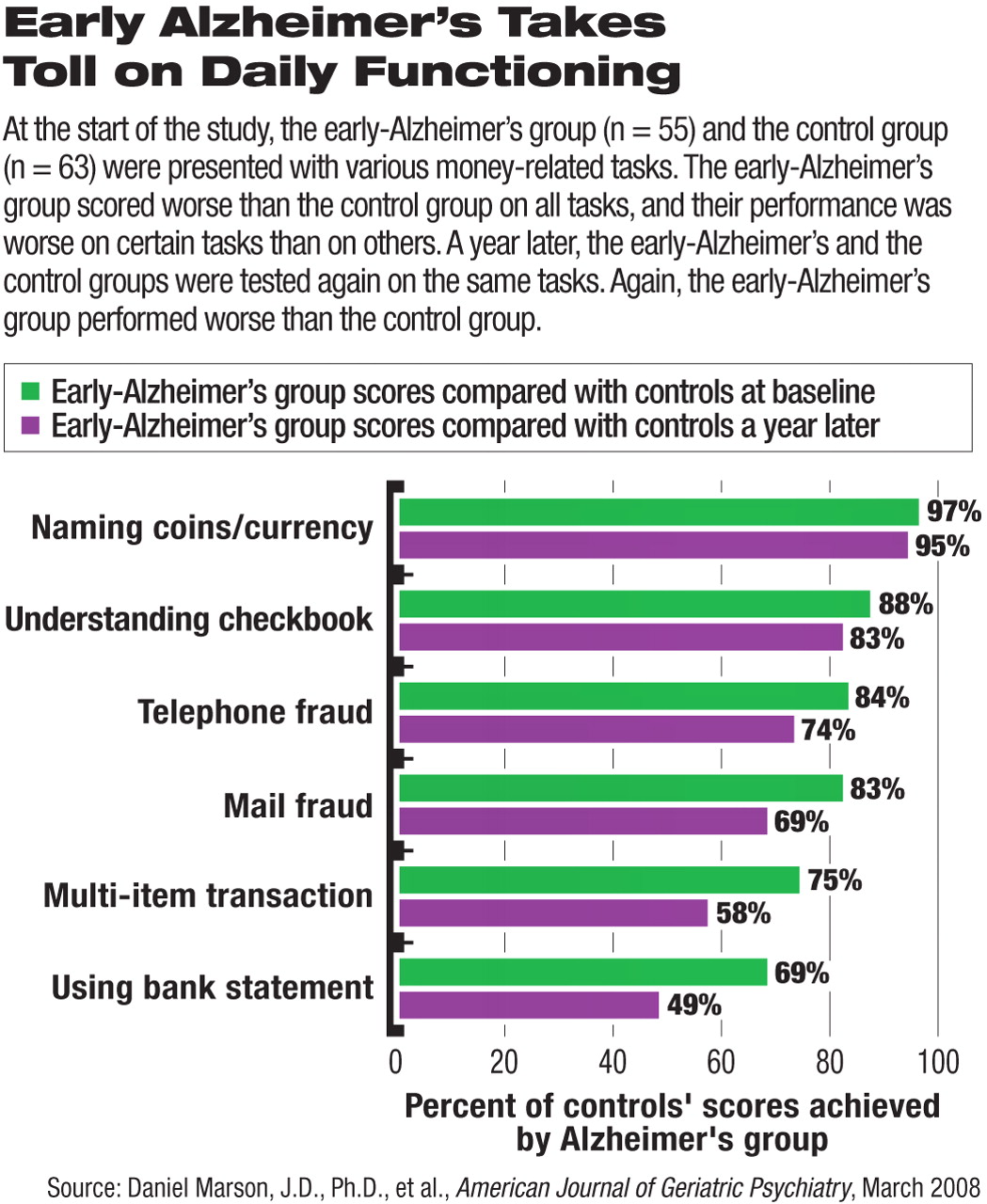

At the start of the study and one year later the researchers evaluated the financial capabilities of 63 mentally healthy older persons whose average age was 66 and 55 older persons with early Alzheimer's whose average age was 71. After taking age, education, and gender differences among the subjects into consideration, results between the two groups were compared.

The financial capabilities of the early-Alzheimer's group, compared with those of the control group, were already quite poor at baseline. The former performed significantly worse on 16 of 18 tasks. For example, when it came to understanding a bank statement, the early-Alzheimer's group scored 74 percent of the score that the controls achieved. When it came to preparing bills for mailing, the early-Alzheimer's group scored only 63 percent of the score that the controls obtained.

Whereas the financial abilities of the control group remained essentially unchanged from baseline to a year later, those of the early-Alzheimer's group declined from what they had been at the start of the study.

For instance, at the start of the study, the early-Alzheimer's group obtained 69 percent of the score of controls in using a bank statement. A year later, it obtained only 49 percent of the score of controls on the same task. At the start of the study, the early-Alzheimer's group obtained 75 percent of the score of controls in providing the correct amount of money for the purchase of three items. A year later, it achieved only 58 percent of the score of controls on the same task (see

chart).

And while at baseline the early-Alzheimer's group performed at 83 percent of the level of controls in detecting mail fraud and at 84 percent of the level of controls in detecting phone fraud, its abilities on these tasks a year later were even less, scoring just 69 percent and 74 percent of controls' scores, respectively. Mail fraud was defined as a letter that offered something too good to be true and intended to deceive. Phone fraud consisted of a call from a fictitious group called Clothes for Kids that pressured listeners to make a donation

All told, the total scores of the early-Alzheimer's group started at 80 percent of those of the controls, but dropped to 70 percent a year later.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.