While the criminal justice system is quietly and slowly shifting from punishment to treatment for illegal drug use, sweeping changes must take place in public policies and in the health care system to resolve the inadequacies in substance abuse treatment in the United States. This was the conclusion of a group of leaders from science, medicine, law enforcement, politics, and public health at a conference in Washington, D.C., in February.

The conference was sponsored by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University and supported with funding from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, American Legacy Foundation, and Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

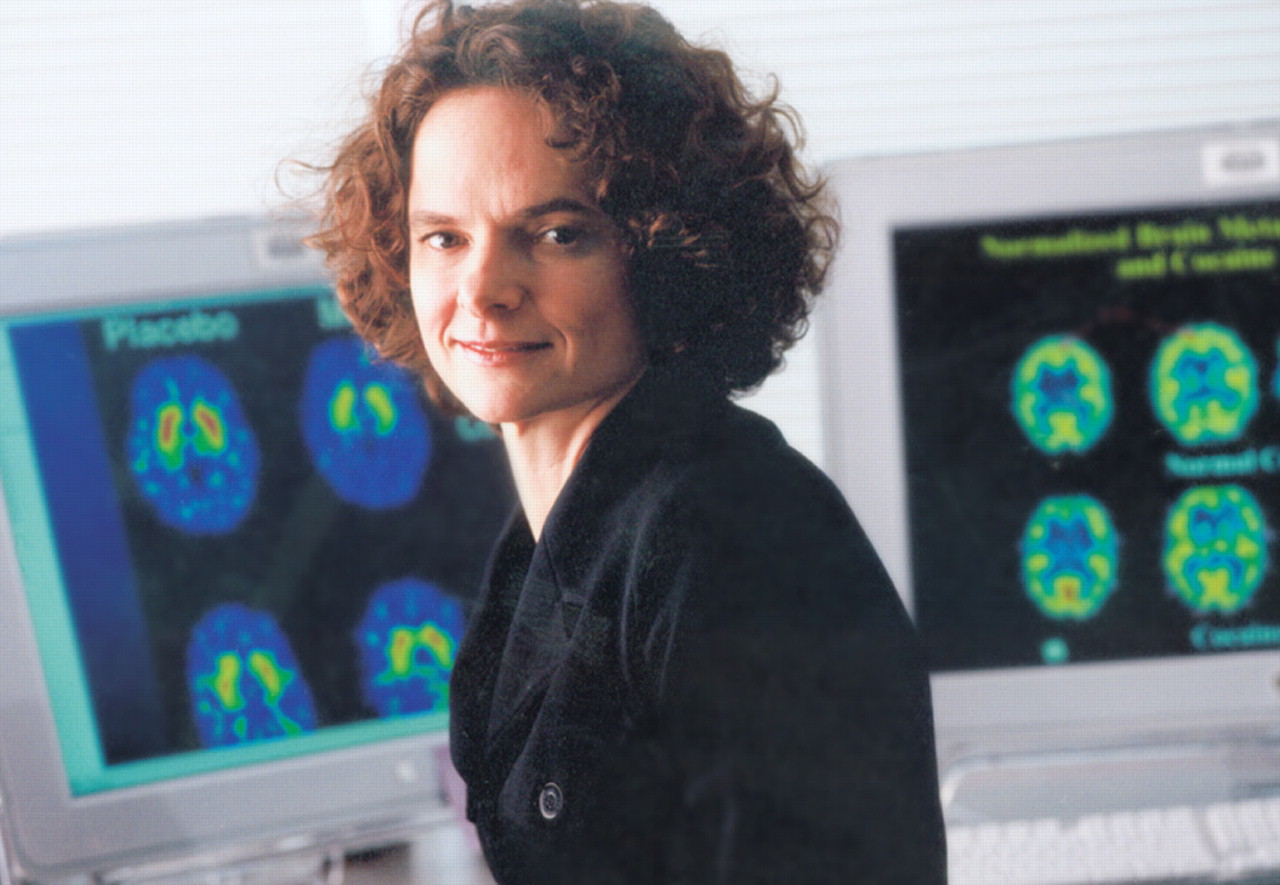

Substance abuse in the United States costs society half a trillion dollars a year, according to Nora Volkow, M.D., director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. She presented cutting-edge research on how addiction grips the biochemical wirings of a person's brain and why simply stopping substance use does not permanently cure addiction. Brain-imaging studies have shown that substance-induced damage lasts long after a person stops taking drugs, and the cravings can be immediately rekindled under stress, she explained. Ongoing treatment maintained throughout recovery is critical to prevent relapse.

For example, Kevin Hauschulz, an individual in recovery who serves as a telephone recovery support coordinator in a community program, described his experience and emphasized that continued support and treatment in recovery, especially his volunteer work with other youth, was a critical component of staying clean.

Throughout the country, access to treatment for substance abuse, however, is limited. “On any given day, 1.2 million adolescents 12 to 17 years old were smoking, 631,000 were drinking alcohol, and 50,000 were abusing inhalants,” said SAMHSA Administrator Terry Cline, Ph.D., citing data from a 2006 survey conducted by the agency and CASA.

The same survey found that a quarter of all community hospitalizations were related to substance abuse. In 2006, 23.6 million individuals needed treatment for substance abuse, but only 2.5 million received specialty care.

“The problem is that substance abuse treatment and prevention have not been integrated into the main-stream health care system,” Cline said. “I look forward to the day when substance abuse and mental illness are treated with the same urgency as any other illness.”

Specialized Treatment a Rarity

Other experts echoed the pervasive shortage of specialized substance abuse treatment. “The medical community has not taken the responsibility for prevention and treatment of substance addiction,” Volkow said.

Louis Sullivan, M.D., founding dean and first president of Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta and a former secretary of Health and Human Services, agreed that many physicians are biased against patients with substance abuse problems and “still view substance abuse as something they should not get involved in.”

Other barriers to adequate substance abuse treatment include lack of reimbursement and limited training for medical students and residents in this field. Even many psychiatrists lack sufficient training to treat addiction, Volkow said. “Medical students don't know what to do with these patients. They feel uncomfortable and ashamed.”

Ralph Lopez, M.D., a professor of pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medical College, discussed the challenges in screening young patients for substance use in primary practice.

Family physicians and pediatricians feel uncomfortable questioning adolescents about drug use in front of their parents, he noted, but screening is important because “the adolescent brain is vastly different from” that of adults, and often lifelong addictions begin at this stage. The key is to build rapport with young patients. “you'll be amazed what kids will tell you once they realize they can trust you,” he said.

Don't Blame Insurance Industry

Leonard Schaeffer, former chair and president of WellPoint Inc., a major insurance company, believes that the lack of coverage for substance abuse treatment should not be blamed entirely on the private insurance industry.

“Most Americans, including physicians, do not view substance abuse as a medical problem,” he said, noting that when employers and the insured do not demand coverage, there is little incentive for the insurance company to offer it. He cited a paucity of research data to convince private insurers that providing reimbursement is cost-effective for them. In addition, there is no social or political pressure for better coverage because neither policymakers nor the public generally consider substance abuse a medical condition.

In contrast, the business case for treating substance abuse is making headway with state and local governments, especially in the justice system.

Government Turns to Treatment

The attitude toward drug offenses has been quietly shifting from punishment and incarceration to treatment, a group of experts noted. For example,“ Florida is investing $38 million on in-prison treatment because of the prohibitive cost of building more prisons,” said then-secretary of the Florida Department of Corrections, James McDonough, who recently left that post. It was difficult to persuade the state legislature that treating offenders with substance abuse was medically necessary, but the economic and social benefits were enough to convince them to make this investment.

Other panelists agreed that substance abuse treatment clearly reduces recidivism, neighborhood crimes, and the cost of building more prisons.

Drug abuse is involved in more than 50 percent of violent crimes and presents a heavy burden for the criminal justice system, according to research cited by Volkow. She noted that substance abuse treatment inside prisons has been shown to be vastly more effective than no treatment in preventing relapses and recidivism after offenders are released.

Drug courts are gaining popularity in more and more states, said Karen Freeman-Wilson, former presiding judge of the municipal court in Gary, Ind., former attorney general of Indiana, and former chief executive officer of the National Association of Drug Court Professionals. ▪