Since the number of Americans who are approaching or reaching elderly status is rising rapidly, and since age is the largest-known risk factor for Alzheimer's disease, some Alzheimer's experts have predicted there will be a dramatic increase in the number of Americans getting the illness during the next few years.

However, this gloomy scenario may not come to pass, a provocative new study suggests.

The study found a marked decline in Alzheimer's and other kinds of dementia among Americans from 1993 to 2002.

The study was headed by Kenneth Langa, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of medicine at the University of Michigan. Results were published online on February 20 in Alzheimer's and Dementia.

In 1993, Langa and his colleagues assessed the cognitive function of a nationally representative sample of older Americans (more than 7,000 subjects aged 70 or older). The assessments were conducted either over the phone or in person. Most individuals over age 80 were evaluated in person.

Subjects were given, for example, an immediate and delayed 10-noun recall test to measure memory, a counting-backward test to measure speed of mental processing, and an object-naming test to measure knowledge and language.

The researchers then rated the subjects using a 35-point cognitive scale. A score of 11 or above was defined as normal cognitive function, a score of 10 or below as cognitive impairment consistent with dementia. The dementia category was further subdivided into mild dementia for those with a score of 8 to 10 and moderate/severe dementia for those scoring from 0 to 7.

In 2002 the researchers used the same tests and cutoff scores to evaluate the cognitive function of another nationally representative sample of Americans (again, more than 7,000 subjects aged 70 or older). The researchers compared the outcome for the two groups.

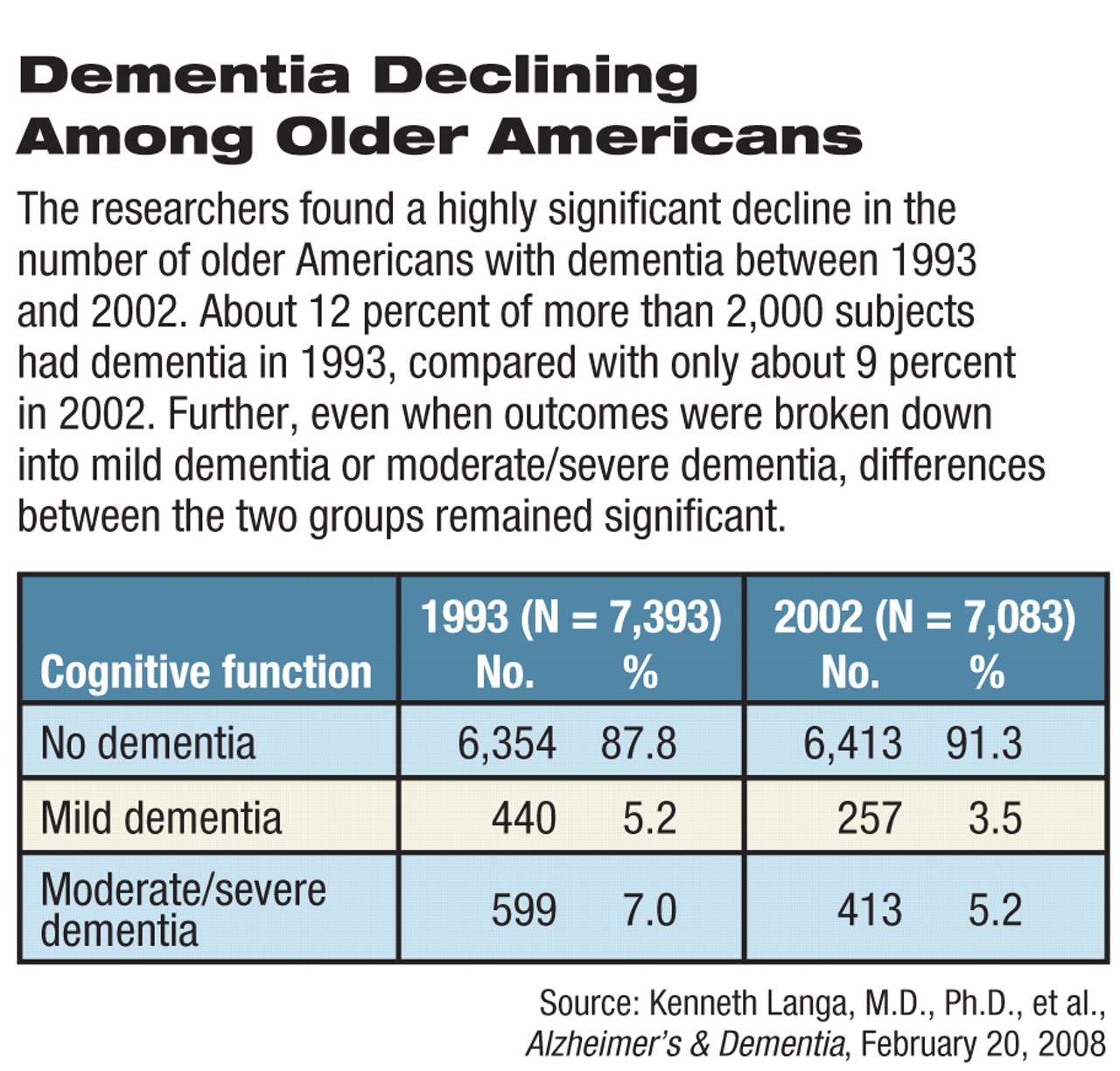

Twelve percent of subjects in 1993 had dementia—that is, had a score of 10 or below on the 35-point scale—compared with only 9 percent in 2002; this was a highly significant difference.

And even when outcomes were broken down into mild or moderate/severe dementia, differences between the two groups were significant. Whereas 5 percent of the 1993 cohort had mild dementia, only 4 percent of the 2002 cohort did. Whereas 7 percent of the 1993 cohort had moderate or severe dementia, only 5 percent of the 2002 cohort did.

Langa and his team are thus optimistic that the prevalence of dementia, and more specifically of Alzheimer's, may be on the decline.

Assuming that there is really a trend in this direction, what might be the reason? Higher levels of education, Langa and his group suggested.

First, just as other researchers have found a protective effect of education against Alzheimer's, Langa and his team found a protective effect of education against dementia in both their 1993 and 2002 groups. Second, Langa and his colleagues found that the 2002 group had significantly more years of education than the 1993 group did. In addition, the researchers determined that the higher levels of education in the 2002 group accounted for about 40 percent of the decrease in dementia prevalence between 1993 and 2002.

So, if education can indeed help ward off Alzheimer's and help reduce its prevalence in an aging population, how might it do so? Langa and his group suggested possible explanations.

Perhaps schooling has a direct positive effect on brain development, and it may be that better-educated people are more likely to take on cognitively demanding occupations than less-educated people are, thus keeping their brains primed to fight off Alzheimer's. Or perhaps the brains of the better-educated individuals are able to sustain greater damage from Alzheimer's pathology or ischemia before reaching a threshold of clinical significance. And finally, the better-educated may be more likely than the less-educated to pursue“ brain-healthy lifestyles, such as better control of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk factors, [and to have] better access to health care interventions that might help preserve cognitive function.”

Among the practical implications of these results are “that good control of cardiovascular risks, continued cognitive stimulation, and staying connected with social networks may have a beneficial effect on preventing or delaying cognitive decline,” Langa told Psychiatric News.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Harvard University Interfaculty Program for Health Systems Improvement.

An abstract of “Trends in the Prevalence and Mortality of Cognitive Impairment in the United States: Is There Evidence of a Compression of Cognitive Morbidity?” is posted at<www.alzheimersanddementia.org/article/PIIS155252600800023X/abstract>.▪