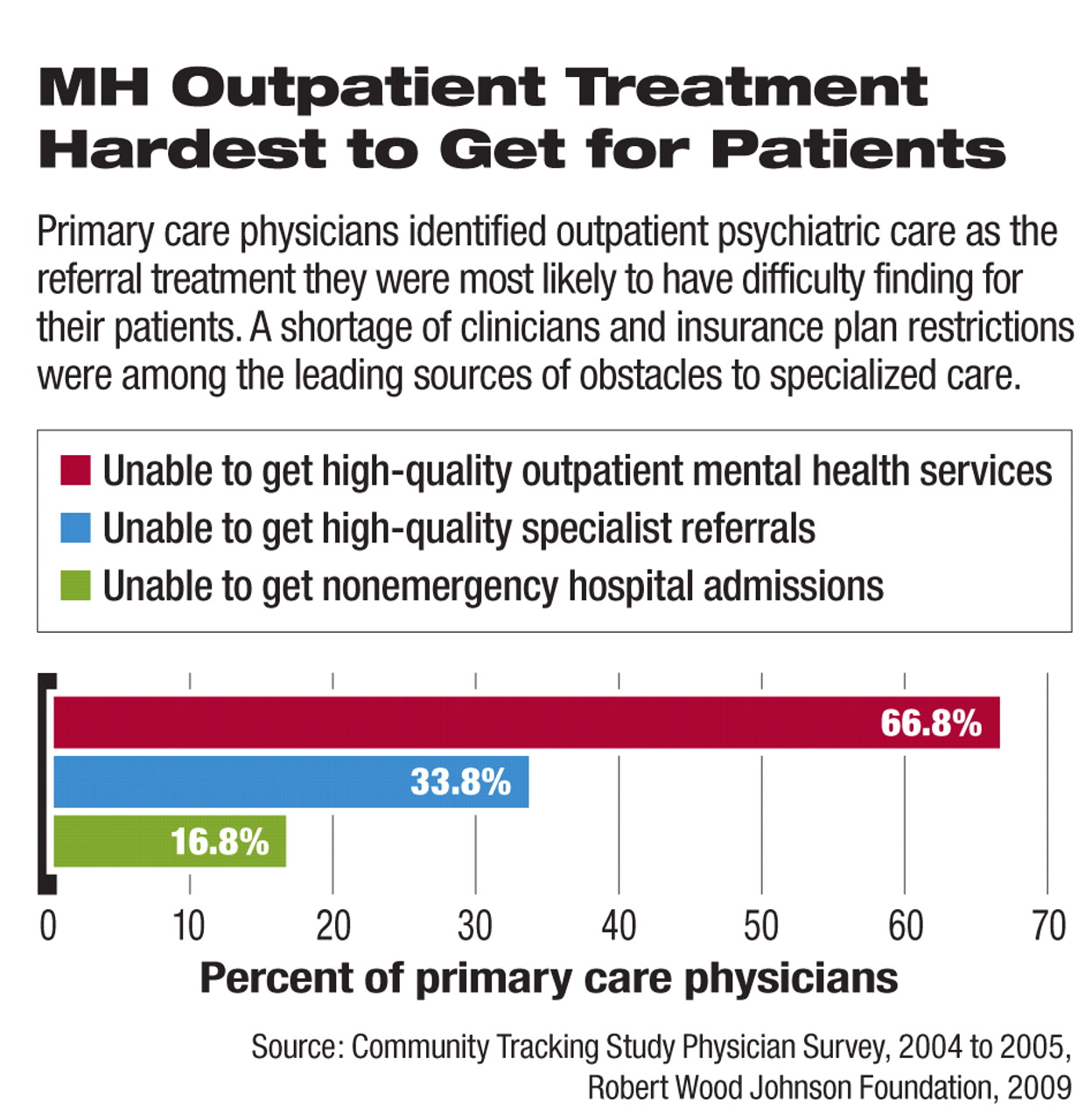

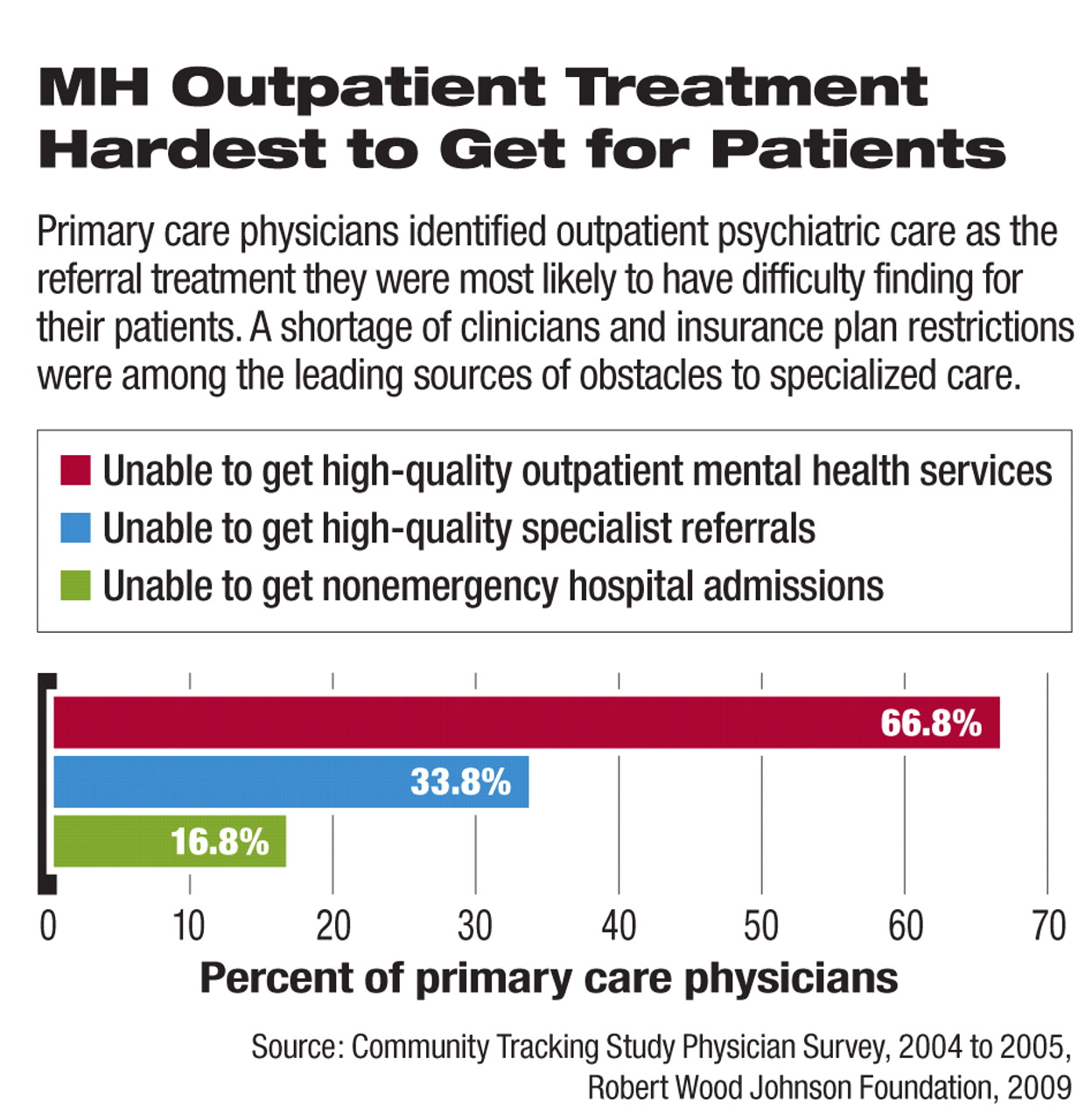

Two-thirds of 6,600 primary care physicians surveyed in 60 U.S. communities said they are unable to obtain outpatient mental health care for their patients, according to a report by researchers from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC) published in April's Health Affairs.

The researchers discovered that the mental health treatment difficulties occurred far more frequently than referrals to other types of health care services. They also found that mental health manpower and inadequate insurance coverage play a big role in the problem.

“From the perspective of primary care physicians, the study's findings suggest that lack of access to mental health services is a serious problem—much more serious than for other commonly used medical services,” said Peter Cunningham, Ph.D., a senior fellow at the HSC and an author of the study, in a written statement.

Based on the survey, conducted in 2004 and 2005, Cunningham and his colleagues found that mental health referrals proved more elusive for the primary care physicians surveyed than other kinds of medical care referrals, including specialty non-mental health care. Specifically, the rate of difficulty in obtaining needed outpatient mental health care for patients was more than twice the rate reported for any of three other common referrals: other specialists, imaging services, and nonemergency hospital admissions. For example, almost 67 percent of the primary care physicians reported that they couldn't get mental health services for some of their patients, compared with 34 percent who reported other non-mental health specialist referral obstacles, 30 percent who reported they couldn't get diagnostic imaging, and 17 percent who reported they were unable to obtain nonemergency hospital admissions.

Primary care clinicians cited inadequate health coverage, “insurance barriers,” and an inability to find a mental health clinician to care for their patients, among the chief reasons their patients could not obtain care for psychiatric conditions.

Among primary care providers, who included general internists, family and general practitioners and pediatricians, the pediatricians were more likely to report problems in getting mental health care for their patients. Pediatricians cited a shortage of providers for children and health plan barriers such as a lack of coverage for mental health services.

The study consistently found a lower number of psychiatrists in areas of the country where there were more problems getting mental health services due to a shortage of providers. Physicians in counties with moderate or large numbers of psychiatrists (defined by the authors as at least eight psychiatrists per 100,000 residents) were about 12 percent less likely to report provider shortages as one reason for the lack of available mental health referral care than were clinicians in counties with fewer psychiatrists.

The authors were surprised that counties with a high number of psychiatrists had a greater probability of patients being denied mental health care because of either “plan barriers” or inadequate or a lack of coverage among patients compared with counties having smaller numbers of psychiatrists. Although areas with large numbers of psychiatrists were likely to have greater mental health care utilization overall, the authors theorized that health insurance plans in those locations may attempt to limit the utilization of psychiatric care through greater restrictions on utilization or less generous benefits.

The study “clearly is an indicator that there are ongoing problems with access to mental health care,” said Anita Everett, M.D., chair of APA's Council on Healthcare Systems and Financing.

Still, in many areas with small numbers of psychiatrists, the researchers found that the shortage of such clinicians had a greater impact on the ability to obtain mental health care than did obstacles stemming from a lack of coverage and from insurance-plan barriers.

Problems accessing mental health care that stemmed from a lack of insurance—and underinsurance by policies that provided no or lesser mental health care coverage—were most often cited as factors in patients not receiving needed care. It is not known yet whether access to mental health care was enhanced by the federal mental health insurance parity law enacted in 2008, said the authors. They concluded that state mental health parity laws have had only a modest effect on reducing mental health access disparities when compared with states that do not have insurance parity laws.

“Even with national parity legislation, large gaps in mental health access will likely remain, and the new law will have no effect on the severe access problems of the uninsured as well as problems related to the shortage of mental health care providers,” Cunningham and his coauthors wrote.