Prescription drug management practices employed by Medicaid programs to control costs appear to be associated with increased problems with access to medications and with adverse events.

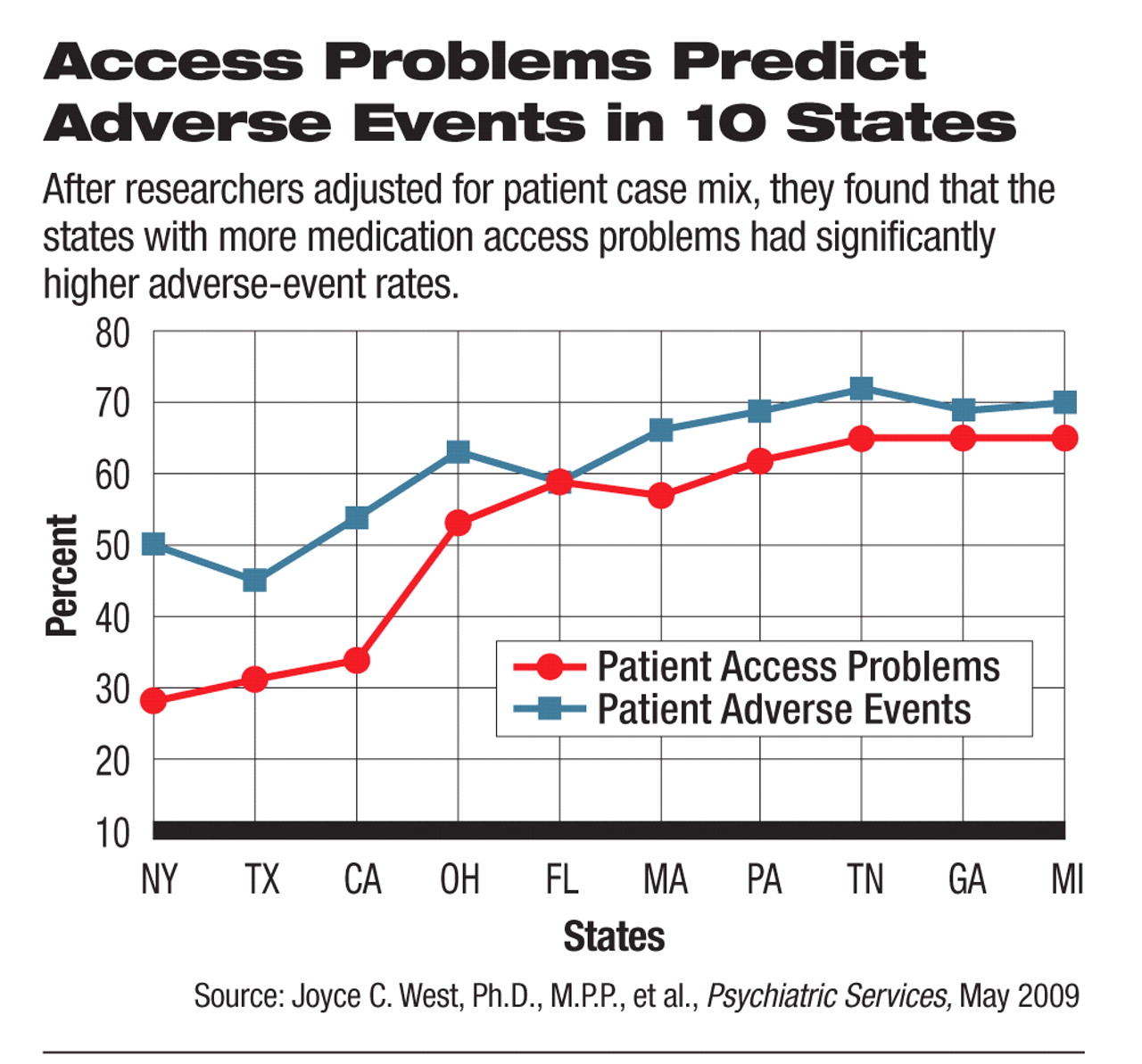

A survey of psychiatrists treating Medicaid patients in 10 states found that close to half of the patients had experienced at least one medication-access problem. But the survey also revealed significant differences in rates of access problems and adverse events across the states; those states with increased access problems also had increased adverse events.

The study, “Medicaid Prescription Drug Policies and Medication Access and Continuity: Findings From 10 States,” appears in the May Psychiatric Services.

“What was striking was the considerable variation in rates of access problems and adverse events across the states and the consistent patterns of association between utilization-management strategies and access problems, and access problems and adverse events,” said Joyce West, Ph.D., M.P.P., senior scientist with the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education, in an interview with Psychiatric News. “Overall, our findings indicate that Medicaid prescription drug management policies based primarily on cost rather than clinical considerations may result in significant human, economic, and social costs.

“It is particularly troubling that there are many opportunities to improve quality and continuity of pharmacologic treatment for this vulnerable population,” she continued. “The prescription drug care management practices for severely mentally ill patients should clearly focus more on promoting continuity of care. Yet in this study we see these practices were associated with significant gaps and disruptions in treatment—which were then associated with increased emergency room visits, hospitalizations, homelessness, and even incarceration.”

Five hundred psychiatrists were randomly sampled from the AMA's Physician Masterfile in 10 states: California, Florida, Georgia, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Texas, for a total of 4,866 psychiatrists. (In Tennessee only 366 psychiatrists were available.)

Psychiatrists were randomly assigned one of 21 start days and times during their last typical workweek to report on their next two Medicaid patients. Responses were obtained from 62 percent of the sample, 2,671 psychiatrists; 32 percent, or 857, met the study eligibility criterion of having treated Medicaid-only patients in their last typical workweek, resulting in clinically detailed data for 1,625 Medicaid patients.

Data were collected by mail from September 2006 to December 2006 on patient characteristics, prescription drug utilization-management practices, medication-access problems, and adverse events experienced since January 1, 2006. In comparing access problems and adverse events across the 10 states, researchers adjusted for differences in patient case mix to control for sociodemographic and clinical confounders.

Overall, 48.3 percent of the patients were reported to have experienced at least one medication-access problem. Rates of access problems varied significantly across the states, with a 37.6 percent absolute difference between the lowest (New York, 27.1 percent) and highest (Michigan, 64.7 percent) rates.

Overall, 34 percent of patients were unable to access clinically indicated medication refills or new prescriptions because they were not covered or approved by Medicaid. In other cases, clinicians would have preferred to use clinically indicated medications but could not prescribe them because patients could not make copayments or because medications were discontinued or temporarily stopped because of coverage, administrative or management issues, or a problem with patient copayments.

Problems with access were consistently associated with adverse events. Adjusting for patient case mix, researchers found that patients with a reported medication-access or medication-continuity problem had a 3.6 times greater likelihood of a reported significant adverse event (see chart). Adverse events were defined as an emergency visit, psychiatric hospitalization, increase in suicidal or violent ideation or behavior, homelessness, or incarceration in prison or detention in jail.

Overall, 72.2 percent of patients with medication-access problems were reported to have experienced an adverse event, compared with 49.4 percent for patients with no reported access problems.

“States should consider other best practices to improve the management and continuity of prescription drugs for this population,” the authors wrote. “The use of medication support and adherence strategies shown to be effective in assertive community treatment models should be explored. This includes ordering and delivering medications to patients, providing education about medications, and monitoring medication compliance and side effects. Disease-management strategies and more effective use of technology, such as pill boxes with paging systems, have also been suggested to enhance medication continuity.”

Irvin “Sam” Muszynski, J.D., director of APA's Office of Healthcare Systems and Financing, said the study findings should prompt Medicaid programs to rethink their utilization management practices for severely mentally ill patients. “The findings speak for themselves and should make it clear that overall costs savings from these practices are illusory.”