What happens to 8-year-old boys who do not live with both biological parents, misbehave, and are very anxious?

They may be more likely to kill themselves once they become adolescents or young adults than are boys of the same age who do not fit this profile, a Finnish study has found.

The investigation, which included more than 5,000 subjects, appears to be the first longitudinal population-based study to see whether there is any link between early childhood psychopathology and suicide in adolescence or young adulthood, the authors noted. Results were published in the April Archives of General Psychiatry. The lead investigator was Andre Sourander, M.D., a professor of child psychiatry at Turku University Hospital in Turku, Finland, who is also affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry at Columbia University in New York City.

Since suicide is a rare event in most countries, a very large number of subjects is required to find any links between early childhood and adult suicide. But thanks to the Finns' stellar recordkeeping—every Finnish citizen receives a personal identification number upon birth that is also used in hospital discharge registers and death certificates—such a study was feasible.

In 1989, some 5,300 8-year-olds—evenly split between boys and girls—were enrolled in the study. The investigators gathered information about their families, school performances, and psychological-behavioral states. The last was culled from three sources—parents, teachers, and the children themselves.

The parents and teachers filled out a questionnaire called the Rutter questionnaire, which is a validated child psychiatric instrument widely used in child psychiatric research. It included questions that the parents and teachers answered on a scale of 0 to 2. The questions asked whether a child was shy, anxious, or withdrawn; whether he or she was hyperactive; and whether he or she engaged in misconduct—for example, disobedience, defiance, fits of temper, stealing, lying, or aggression and cruelty toward others. Parent and teacher information about each child was combined to generate a sum score.

The children filled out a questionnaire called the Children's Depression Inventory to help determine whether they were depressed. The children answered the questions on a scale of 0 to 2.

In 2005, when the subjects were 24 years old, the investigators used their personal identification numbers as well as hospital discharge registers and death certificates to see whether any of them had been hospitalized for severe suicide attempts or had died by suicide since the study had started. Fifty-four had—27 male and 27 female.

The investigators looked to see whether the family environment, school performance, or psychological-behavioral state of these 54 subjects at age 8 could have predicted their serious suicide attempt or death by suicide by age 24. The answer was “no” for females, but “yes” for males.

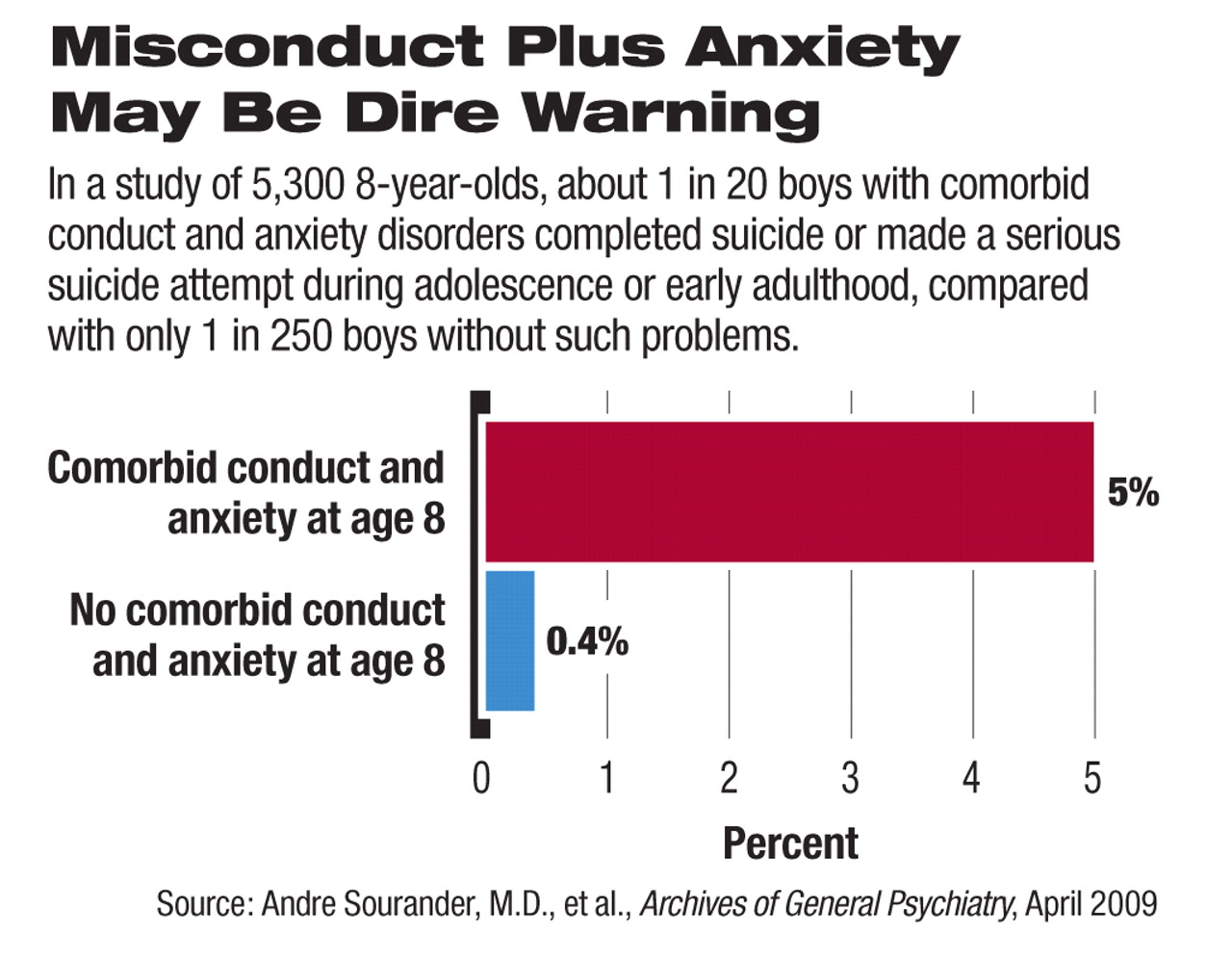

Among the males at age 8, not living with both biological parents, engaging in misconduct, being hyperactive, or being anxious predicted suicide by age 24. The strongest predictor was conduct problems and anxiety at age 8.“ Remarkably, approximately 1 in 20 males with comorbid conduct and [anxiety] problems at the age of 8 years completed or seriously attempted suicide during adolescence or early adulthood compared with only 1 in 250 males in the reference group,” Sourander and his group pointed out in their study report.

In contrast, being depressed at age 8 did not predict suicide outcome.

“Our findings suggest that early recognition and effective treatment of early childhood psychiatric problems among males may have an effect on the risk of later severe suicidal behavior,” the researchers noted. Such early intervention is especially crucial since “almost none of the males in the study who were at high risk of severe suicide outcome had used mental health services during adolescence,” Sourander told Psychiatric News.

“Considering child mental health in the context of later health outcomes will require a significant shift in thinking on the part of health professionals,” Sourander said. “Today adult psychiatry versus child and adolescent psychiatry are rather separate fields. However, population-based longitudinal studies such as this one show a strong continuity between childhood factors and adult problems.”

One reason why they could find no links between early psychological problems in females and later suicide risk, Sourander and his team believe, is because female suicide risk is strongly associated with anxiety and depression, and females usually start experiencing these affective disorders after puberty begins.

The study was funded by the Sigrid Juselius Foundation.