What makes expert witnesses credible with jurors? When they show confidence, but not bravado, a new study suggests.

The study was headed by Robert Cramer, a doctoral student in psychology at the University of Alabama. Results appeared in the March Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law.

Participating in the study were more than 300 university undergraduates taking an introductory psychology course who played mock jurors. The subjects were randomly divided into three groups. Subjects in each group were shown a video portraying two mock expert witnesses testifying about their evaluation of a convicted murderer during a postconviction sentencing phase. But the script was slightly altered for each of the three groups so that the two witnesses displayed low confidence, medium confidence, or high confidence.

For example, the witnesses in the low-confidence video had awkward posture, showed signs of anxiety, used a quivering tone of voice, and often said“ you know” to seek assurance. Witnesses in the medium-confidence video had good posture, showed comfort and poise, moderately paced their speech, and often used the term “I am reasonably certain.” Witnesses in the high-confidence video leaned forward, spoke loudly and rapidly, and often used the term “I am certain.”

After the mock jurors had viewed the video version to which they had been assigned, they rated the mock witnesses with the Witness Credibility Scale, which contains 20 items concerning confidence, likability, trustworthiness, and knowledge and gives an overall credibility score.

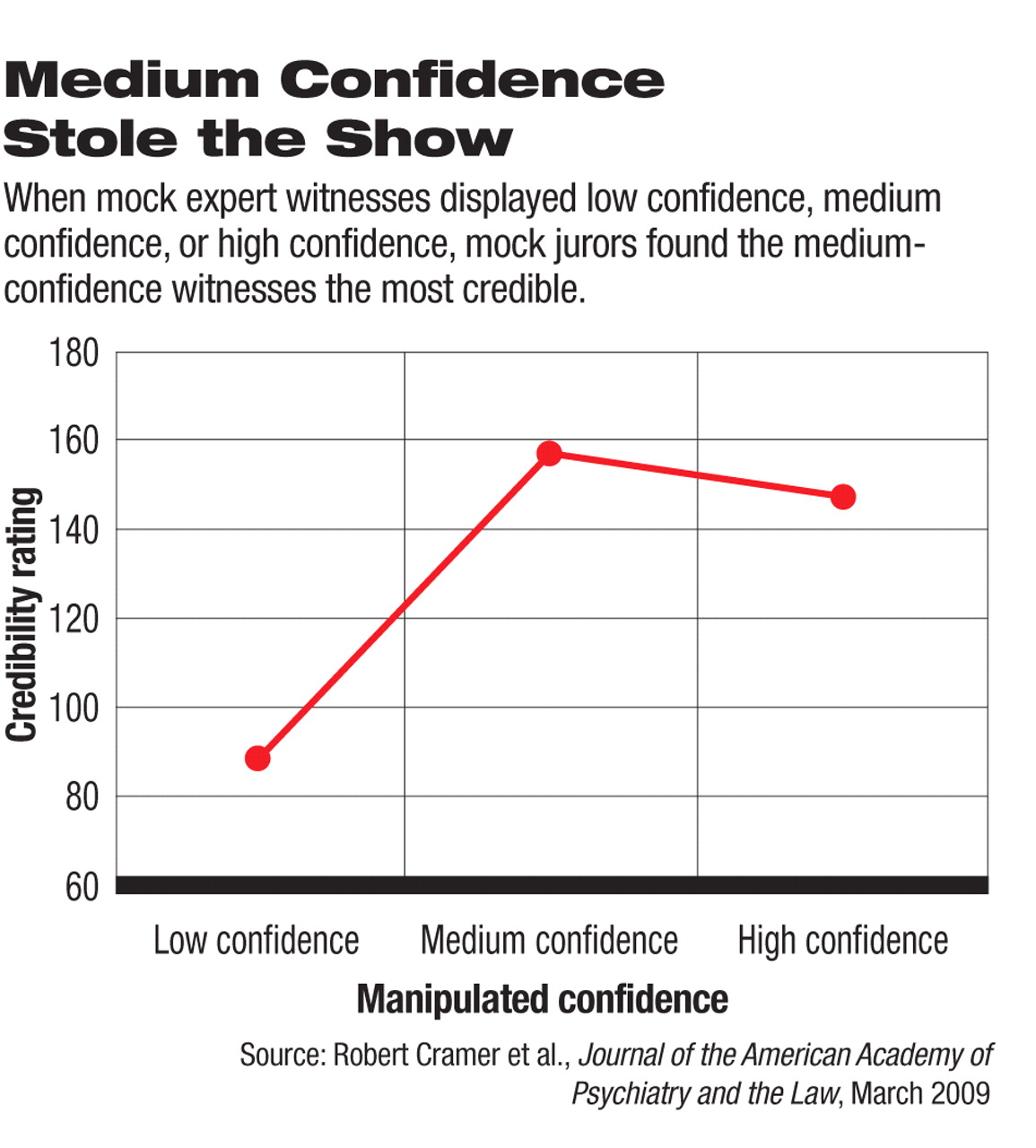

The low-confidence witnesses were rated as significantly less credible than both the medium-confidence and high-confidence witnesses, but the medium-confidence witnesses were rated as significantly more credible than the high-confidence witnesses.

Or as Cramer and his group commented in their paper, “Confidence does not equal credibility, which means, pragmatically speaking, that the most effective witness may not be the supremely confident witness.”

This finding stands, interestingly, in contrast to that of another study—that lawyers and judges prefer expert witnesses who display high confidence.

Cramer and his colleagues also wanted to find out whether the mock jurors' personalities had influenced their credibility ratings of the mock expert witnesses. To find out, they evaluated each mock juror on the personality traits of neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, then looked to see whether there were any significant links between the personality traits that the mock jurors possessed and their credibility ratings of the mock expert witnesses.

A significant link was found only for extroversion: mock jurors who scored high on extroversion had rated mock witnesses as significantly more credible than had mock jurors who scored low on extroversion. This was the case regardless of whether mock witnesses had portrayed low confidence, medium confidence, or high confidence.

Why might extroverted jurors find witnesses more credible than introverted jurors do? Extroverts are positive, friendly, gregarious individuals who seek out positive interactions with other people. So extroverted jurors may find expert witnesses credible simply because they, the jurors, feel a positive rapport with them, Cramer and his group speculated. And if that is indeed the case, they added, then extroverted jurors might find expert witnesses especially credible if the witnesses themselves are extroverted.

“Our findings have practical implications for both witness preparation and jury selection,” the researchers concluded. For instance, if expert witnesses have good posture, but do not lean forward to persuade jurors; speak with a fair amount of certainty, but not cockiness; and speak at a measured pace rather than rapidly, they are apt to exude just the right amount of confidence to persuade jurors that their testimony is accurate, the researchers believe. And if lawyers want jurors to believe expert witnesses, then they might do well to select extroverted jurors.

The study was funded by the American Society of Trial Consultants.

“Expert Witness Confidence and Juror Personality: Their Impact on Credibility and Persuasion in the Courtroom” is posted at<www.jaapl.org/cgi/reprint/37/1/63>.▪