In the years after the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) imposed the boxed warning about risk of suicidality on antidepressant labeling, the effects of this decision, including unintended consequences, have been felt widely, according to a study published in the June Archives of General Psychiatry.

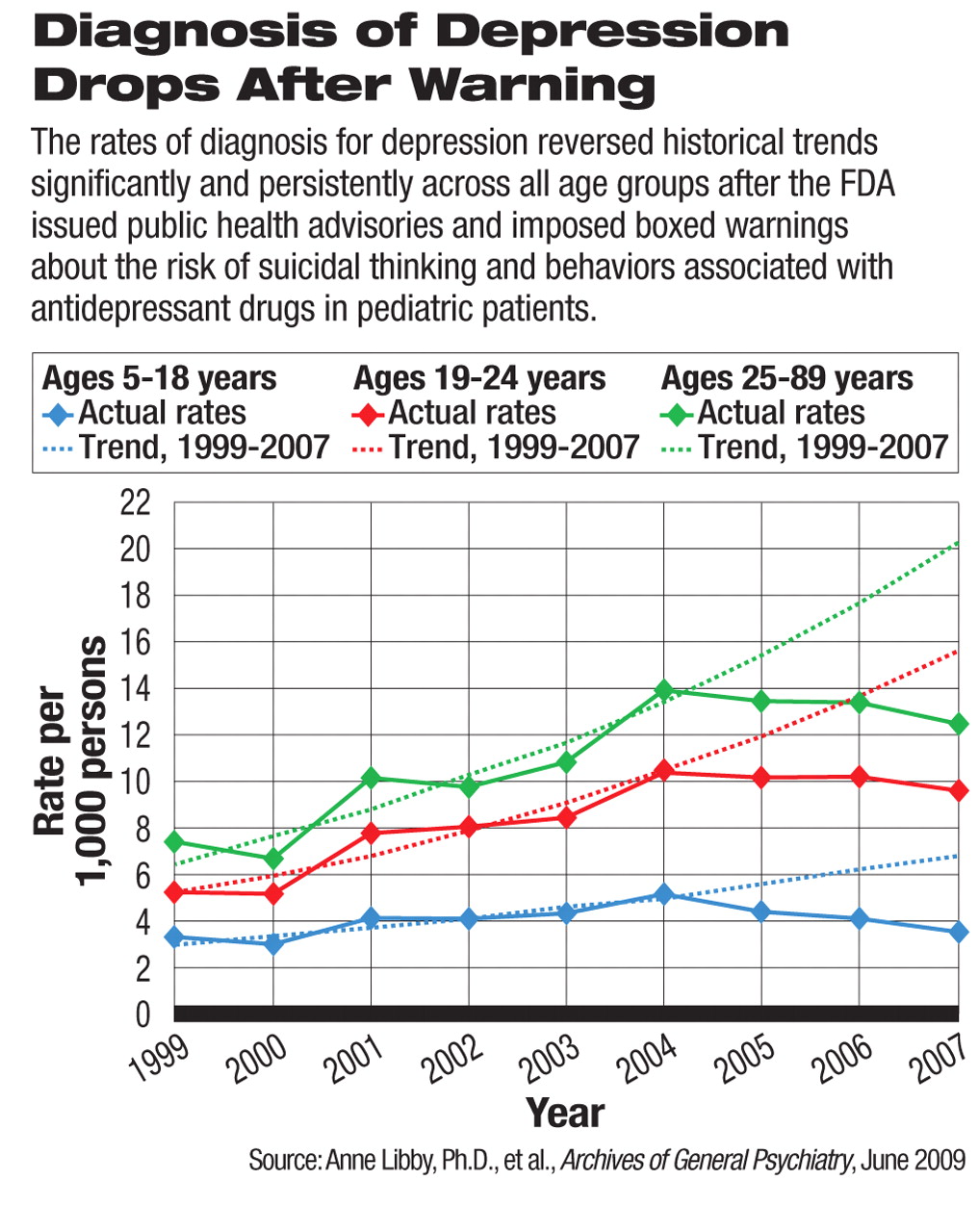

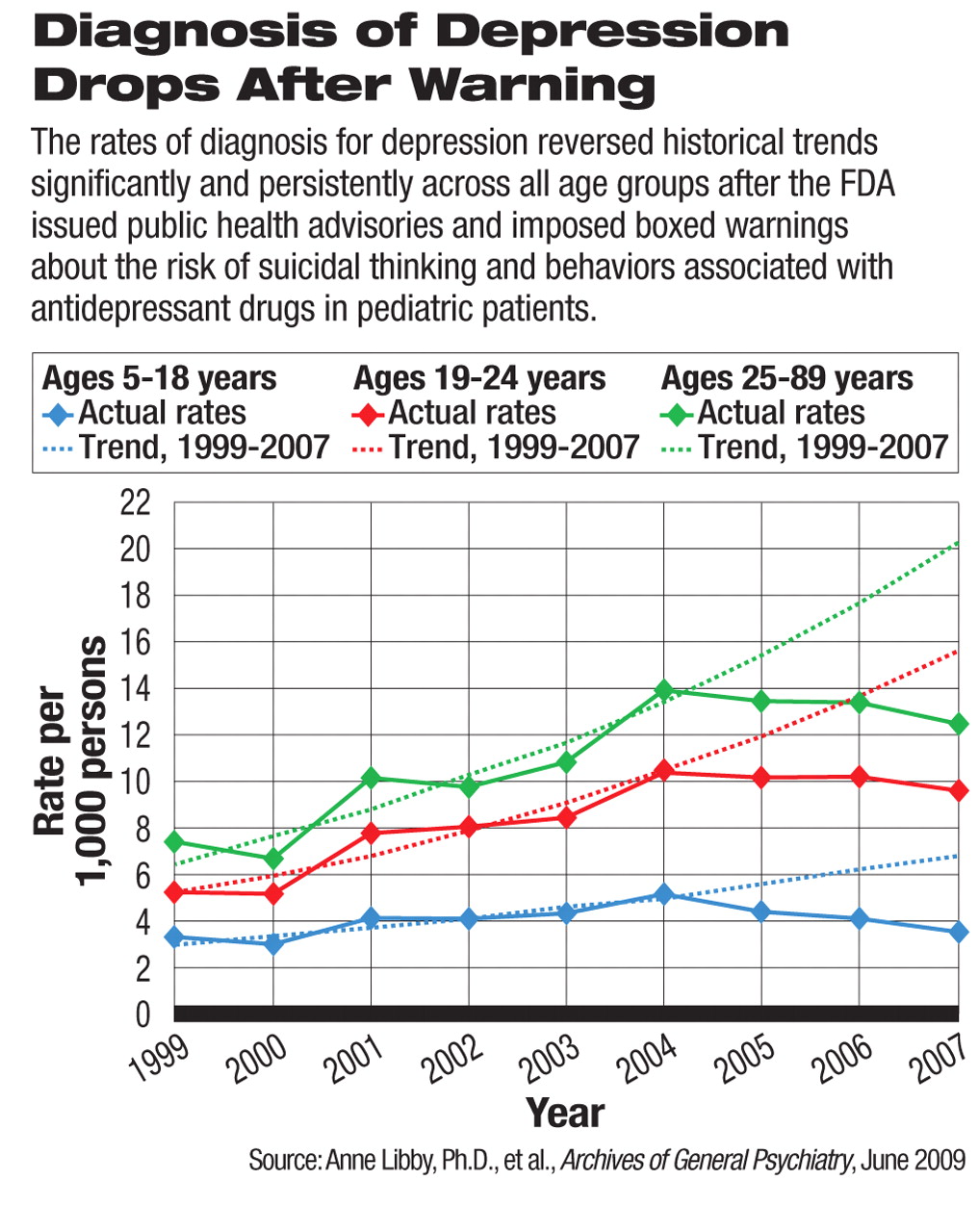

In ambulatory care settings, the national rate of diagnosis for pediatric depressive episodes dropped significantly from 2004 levels, after the FDA issued a Public Health Advisory about increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors associated with antidepressant medications. This declining trend persisted through the end of the study period, June 2007. This was a reversal of the trend from 1999 to 2004, during which time the rate of diagnosed depressive episodes steadily increased. By 2007, the rate of depression diagnosis for new pediatric patients (3.5 per 1,000 individuals) had dropped back to near the 1999 level (3.2 per 1,000 individuals) and far below what the projected trend would have been.

The researchers, led by Anne Libby, Ph.D., an associate professor at the University of Colorado, Denver, School of Public Health, also detected a spillover effect of the regulatory warning beyond the targeted patients. The rates of diagnosis in young adults and other adults, populations that were excluded from the warning during the study period, also declined in parallel with pediatric diagnoses, which also reversed a rising trend before 2004.

Beginning in late 2003, a barrage of media coverage about the suicidality risk associated with antidepressants and a series of regulatory investigations and actions in both the United States and Europe drew substantial public attention. A boxed warning about these drugs' risk in patients under age 18 was added to antidepressant labels in February 2005.

In May 2007, the FDA expanded the boxed warning to cover young adults aged 18 to 24. However, the agency also revised the boxed warning to include language about suicide risk reduction in patients aged 65 or older and that depression and other psychiatric disorders “are themselves associated with increases in the risk of suicide.”

Primary care physicians and pediatricians were the main contributors to the reduced number of depression diagnoses. Before the boxed warning, these clinicians had made a growing proportion of depression diagnoses. After the warning, they seemed to shy away from making the diagnosis and prescribing pharmacotherapy.

The FDA-required label warning for antidepressant drugs has never contained language about the diagnosis of depression or suicidality risk in adults beyond age 24. Therefore, declining diagnosis rates, which closely followed the timeline of the regulatory actions and spillover effects to adult patients in both diagnosis and treatment, were considered unintended consequences by the study authors, while the effects on antidepressant treatment for children and young adults were intended consequences.

From October 2004 to June 2007, the number of prescriptions for selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) within 30 days of new (versus recurrent) diagnoses of depression dropped significantly in pediatric, young adult, and adult patients.

The researchers found, among the possible therapeutic substitutions, a small but statistically significant increase in psychotherapy, which was observed in adult patients only. Prescriptions for serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs, including venlafaxine and duloxetine) also increased for adult patients only. Use of anxiolytic and atypical antipsychotic drugs did not increase in any patient populations. The researchers concluded that there was no noticeable evidence that physicians were substituting alternative treatments to compensate for the decline in SSRI prescribing.

In a study in the June 2007 American Journal of Psychiatry, the same authors had first noted this trend of declining antidepressant prescriptions after the FDA warnings through 2005 (Psychiatric News, June 15, 2007). The current study revealed how the trends persisted from 2005 to 2007.

Along with the warning, the FDA recommended close monitoring after pediatric and young-adult patients are prescribed antidepressants, especially in the first few months. Libby and colleagues had previously published a study in the January 2008 American Journal of Psychiatry indicating no significant increase in the frequency of office visits following antidepressant prescriptions despite the FDA's call for increased monitoring (Psychiatric News, December 21, 2007).

“This study provides further evidence for results of the 'natural experiment' launched by the FDA's interpretation of suicide risk from spontaneous adverse-event reports in clinical trials of antidepressant medications,” Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., told Psychiatric News. He is executive director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education and director of research at APA.

“The decision to add a black box for antidepressants was intended to reduce the risk of suicide associated with use of these medications. Although precise estimates of causation are not possible, it is now clear that the black-box warnings have not reduced the rate of completed suicides in this country. In fact, there is evidence that the rate has increased since the prevalence of depression treatment in the U.S. has dropped following the addition of the black-box warning,” said Regier.

There was so much concern about the consequences of antidepressant warnings that in July 2008, an FDA advisory panel voted against the agency's plan to impose a similar boxed warning for the labels of antiepileptic medications, also based on adverse-event reports of suicidal ideation and behavior, Regier pointed out. There is no known precedent for the FDA to remove boxed warnings after they are added to product labeling.

“Because of the well-known bias and weakness of spontaneous adverse-event reports for [psychiatric] medications, APA's recommendation has been to use systematic assessment of suicide risk rather than to rely on the spontaneous reports of suicidal ideation and behavior, which are very common in these patients, as the basis for major public health decisions at the FDA,” said Regier.

An abstract of “Persisting Decline in Depression Treatment After FDA Warnings” is posted at<archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/66/6/633>.▪