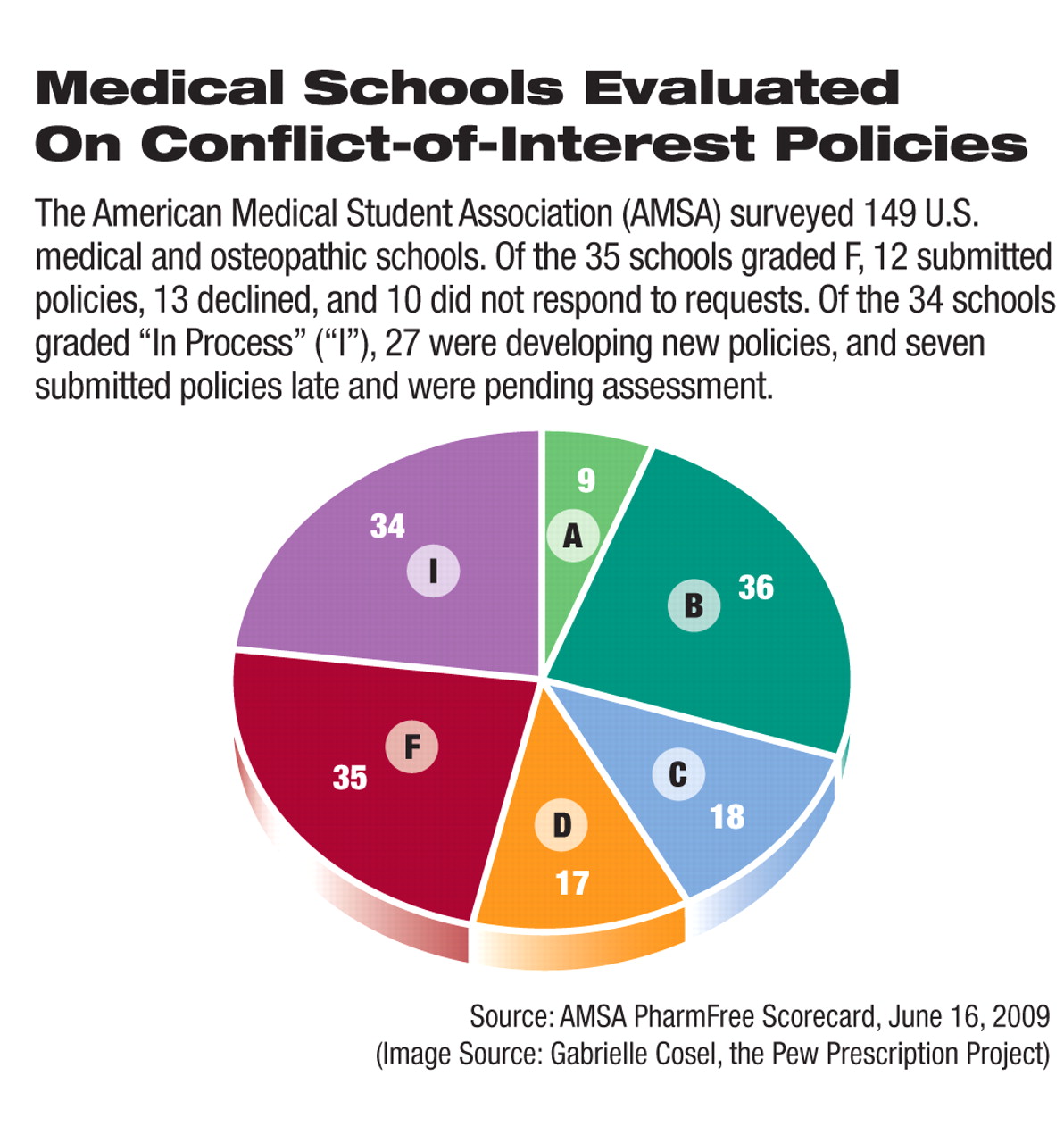

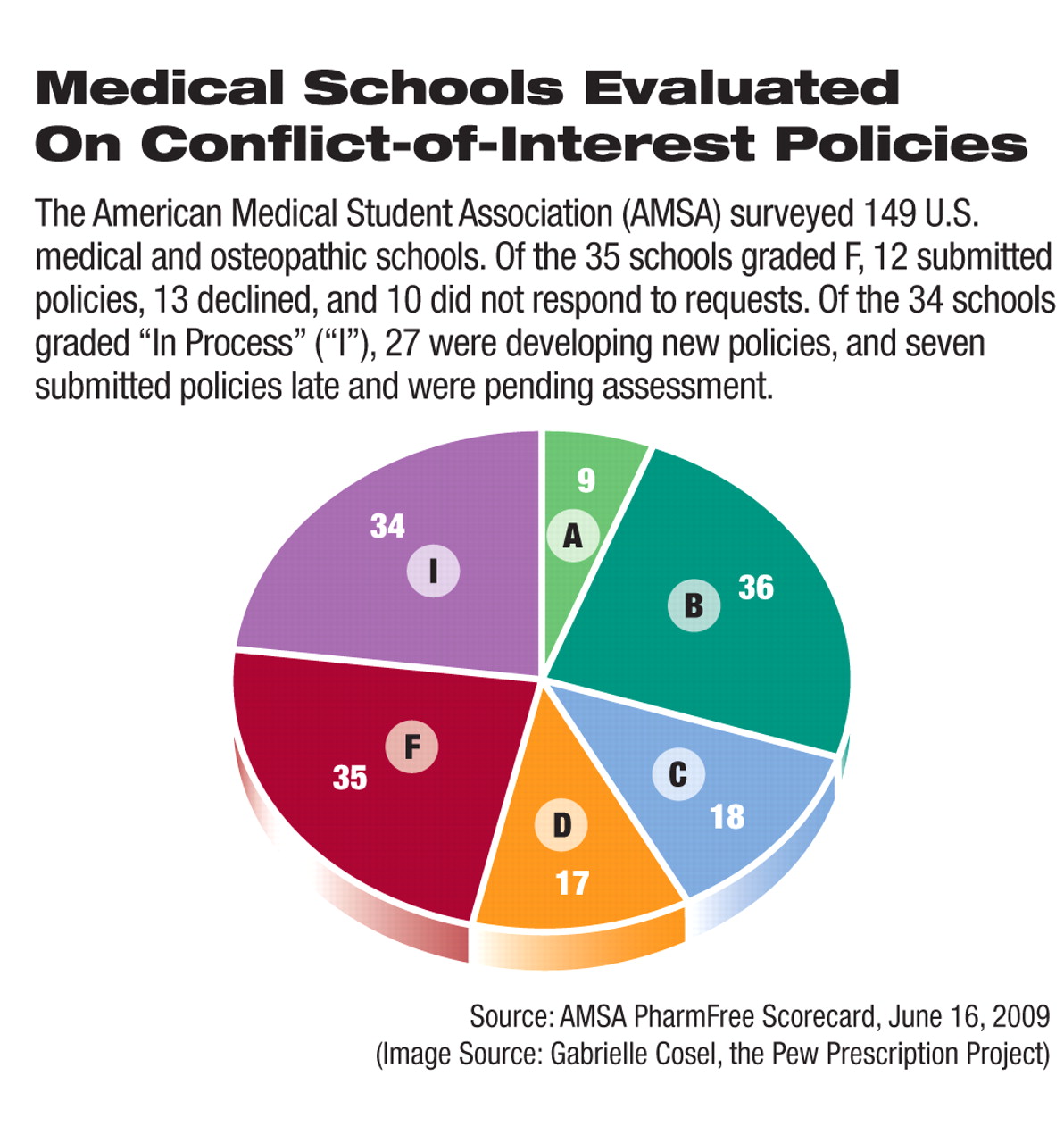

The trend by U.S. medical schools to establish or strengthen policies to regulate and restrict conflict-of-interest problems in relationships with the pharmaceutical industry has picked up steam since 2008, a survey by the American Medical Student Association (AMSA) has found. However, 1 in 4 schools still received a failing grade.

The AMSA PharmFree Scorecard is based on an annual review of conflict-of-interest policies at about 150 medical and osteopathic colleges throughout the country. In collaboration with the Pew Prescription Project, the AMSA developed a rating system to evaluate how stringent and encompassing each school's conflict-of-interest policies are. Two AMSA reviewers who were blinded to the medical school under review independently evaluated each policy on areas such as acceptance of industry gifts and meals; consulting and speaking relationships with industry; purchasing and formulary decisions made by health care professionals with potential conflicts; disclosure requirements for potential financial conflicts; acceptance of industry support for education, scholarships, and trainee funds; sales representatives' access to the medical school or affiliated hospitals; and potential conflicts in teaching and curriculum.

In each area assessed, a policy is given a grade ranging from 0 to 3, with 3 being “model policy,” 2 being “good progress toward model policy,” and 1 being “policy is absent or unlikely to have a substantial effect on behavior.” Institutions that did not respond to or declined to participate in the survey received scores of 0 in every category. The scores were totaled, and institutions with less than 40 percent of the maximum received an F.

Compared with the survey scores from last year (Psychiatric News, July 4, 2008)—the survey's first year—this year's scores indicated that the schools generally have made progress on improving conflict-of-interest policies. The proportion of schools receiving a grade of F decreased from 40 percent to 23 percent. Thirty percent of the schools received a grade of A or B this year, up from just 14 percent in the previous survey. Overall, 21 percent of the schools improved on their previous scores.

Thirty-four schools (23 percent) were designated as “In Process” since they were revising current policies or drafting new policies at the time of the survey.

With an 88 percent response rate, this year's survey had higher participation than did last year's when 70 percent of the schools provided their policies for review. This year just 10 schools did not respond to the survey, and 13 declined to submit their policies.

A week after the scorecard was released, Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) sent a letter to the 23 medical and osteopathic schools that did not respond to or declined to participate in the survey. His June 24 letter asked for each school's conflict-of-interest policies and disclosures of faculty members' financial conflicts if they have grants from the federally funded National Institutes of Health. Grassley has been a vociferous advocate for more regulation of the pharmaceutical industry. He has introduced the Physician Payments Sunshine Act, which will, if passed, require all manufacturers to publicly disclose gifts and payments to physicians.

“Senator Grassley's request was an unintentional byproduct of the AMSA PharmFree Scorecard, but it demonstrates how many different parties are interested in conflict-of-interest issues in medicine,” Branden Pfefferkorn, M.D., AMSA's 2009 PharmFree Scorecard director, told Psychiatric News. “The influence of marketing has been inadequately controlled for too many years, and if medical students and physicians aren't willing to step up and fix the situation, it is becoming clear that state and federal legislators will step in to fix the problem.”

A number of events during the past year continued to fuel the conflict-of-interest debate in academic medicine. In 2008, the Association of American Medical Colleges, for example, issued policy guidelines urging medical schools and research institutions to develop and implement conflict-of-interest policies by 2010. In addition, pharmaceutical companies have widely adopted the new Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) code of conduct for marketing practice, which prohibits sales personnel from giving gifts to or entertaining health care professionals and restricts certain promotional activities (Psychiatric News, October 17, 2008).

Also in recent months on the conflict-of-interest front, several large pharmaceutical companies, under legislative pressure from state and federal governments, began to post online disclosures of payments to physicians. Further, several major medical schools and academic institutions, including Harvard Medical School, Johns Hopkins University Medical School, and the Mayo Clinic, have strengthened their conflict-of-interest and disclosure policies. Earlier this year, a widely publicized Institute of Medicine report called for a ban on all gifts from industry to medical school faculty and all physicians (Psychiatric News, June 5).

The scorecard is part of the AMSA's PharmFree campaign, one goal of which is to promote evidence-based prescribing among physicians in training.

“The AMSA PharmFree Scorecard illustrates the influence and power medical students can have to stand up and disagree with current practices that we feel are not acceptable,” said Pfefferkorn. “With the scorecard, we encourage medical school administrators to at least meet the standards of their peer institutions.... By pairing with the Pew Prescription Project, we not only evaluate school policies but also provide both medical students and school administrators with the resources to successfully effect change.”

Details of the AMSA PharmFree Scorecard, including schools' assessments, are posted at<www.amsascorecard.org>.▪