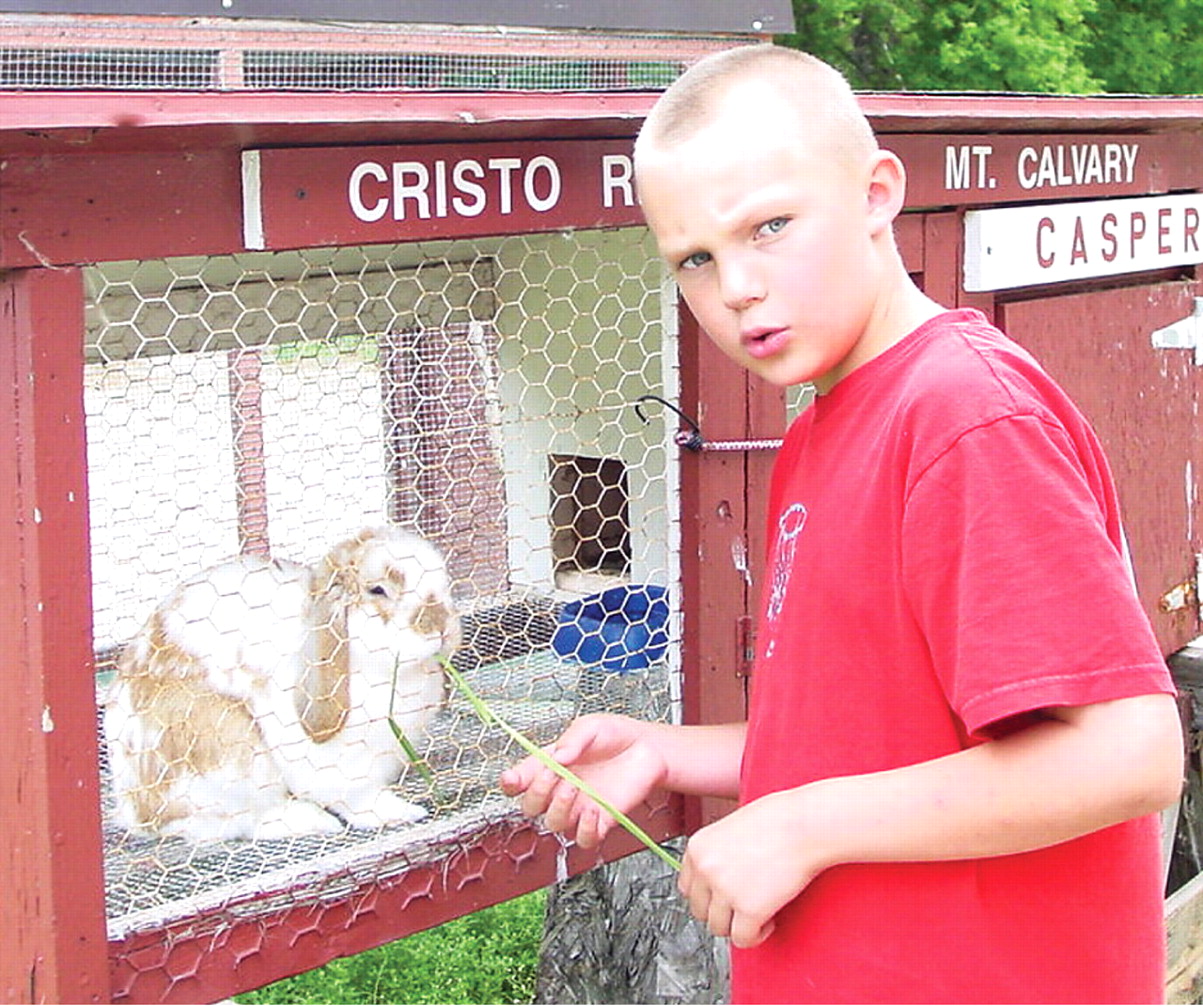

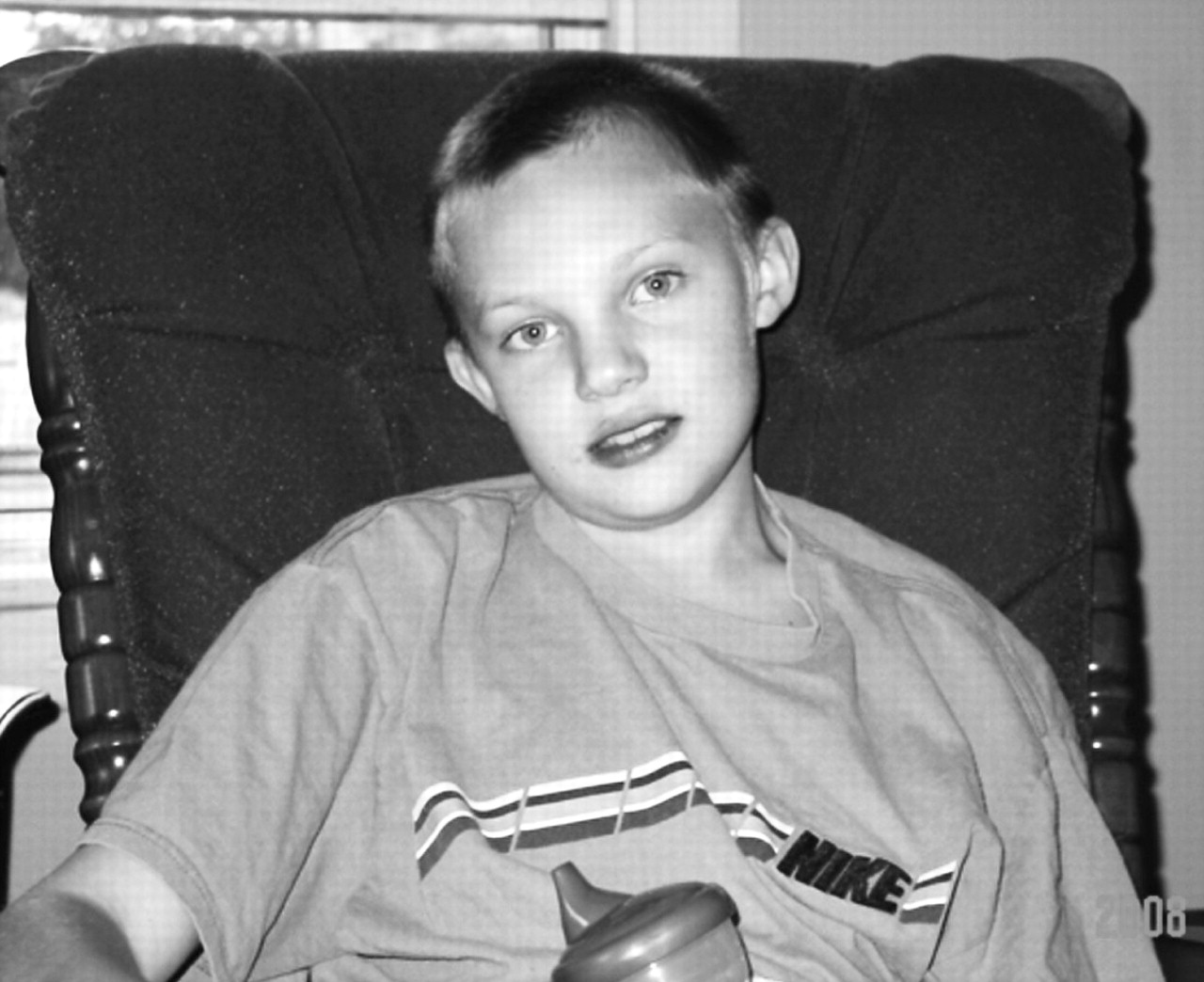

If you're coming to Mason Schroeder's memorial service, be sure to wear your brightest clothes.

That was the word that went out to acquaintances of the vibrant 11-year-old Sheboygan Falls, Wis., boy who died last year of what was determined only six months before his death to be adrenoleukodystrophy. Featured in the 1992 movie, “Lorenzo's Oil,” the disorder is an X-linked genetic condition that progressively destroys myelin tissue insulating nerves of the central and peripheral nervous system. The condition causes any number of behavioral symptoms that mimic, and can be masked by, other psychiatric and developmental disorders.

At the memorial service in Settlers Park in Sheboygan Falls, where members of the community came in their brightest colors to commemorate the boy's life, was Mason's child psychiatrist, Jenna Saul, M.D. She first began treating Mason in July 2006 for what was presumed to be attention-deficity/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

“I struggled with what I could have done differently or sooner, why I wasn't more aggressive about thinking about other diagnoses,” she said.“ In retrospect I don't think I would have ever thought about doing something different or more.”

Though the disease can be detected by a blood test, there is no cure. Expensive bone-marrow transplants can sometimes slow or halt the progression of the disease, as can “Lorenzo's oil”—a 4:1 mixture of glycerol trioleate and glycerol trierucate—along with dietary changes. It is questionable how much difference an earlier diagnosis might have made to Mason's survival.

While there was no neonatal genetic test for the condition at the time of the boy's birth, there is one being pilot tested by researchers at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore. Saul believes that early detection can spare other parents the distress of living in the dark about their child's illness and increase the chances of extending survival with early and aggressive treatment.

Mason's illness is the story of a psychiatrist treating a child with a condition that inhabits a border where psychiatry, neurology, and genetics meet. And it is also the story of how a searing clinical encounter with a baffling illness was the impetus for bringing the cause of universal neonatal genetic screening to the policymaking body of the AMA.

At the memorial service that day last year, the boy's mother, Mary Kelling, sought out the child psychiatrist who had come with the others to say goodbye to Mason. “I told her not for one second would I blame her” for not coming upon the right diagnosis earlier, Kelling told Psychiatric News.

“I was astounded,” Saul said. “Here she was at her son's memorial service and she was seeking me out to look after me.”

Symptoms Didn't Add Up

Saul first began to see Mason as a patient in July 2006 when he was 9. Previously, he had been treated by a pediatrician for ADHD.

“When he first came to see me, there were some quirky aspects to his behavior that made me wonder about a pervasive developmental disorder,” Saul recalled. “But his history didn't support it because he'd had fairly normal early development.”

His progress in treatment came in fits and starts. “At one point he was hospitalized, and I remember thinking that the picture just wasn't adding up,” Saul said. “I was seeing a lot of behaviors that seemed like autism, but the developmental history wasn't consistent.”

She sought to have a pediatric neurologist read an ambulatory EEG on Mason.“ I wanted to be looking for abnormal electrical currents in his brain, and I wanted Mason to be wearing the equipment for 24 hours because the test would be more sensitive,” Saul said. “But the family's insurance would allow only a spot EEG by an in-network adult neurologist.” The spot EEG was normal.

Yet Mason's symptoms continued to be disturbing, and six months later he seemed to be deteriorating. Saul ordered an MRI, which confirmed her suspicions of a serious neurological disorder. “I was paged by a neuroradiologist who told me it was the most disorganized brain scan they had ever seen, and it was consistent with leukodystrophy,” Saul said.

After confirmation of the diagnosis, Mason was referred to the bone-marrow transplant program at the University of Minnesota, but by that time it was too late. “They felt his condition was so advanced that by the time they would be able to decelerate the process with a bone marrow transplant, he would have been in a vegetative state,” Saul said. “They gave him six months to live. I saw him once or twice before he died.”

Shortly before Mason's death, Kelling began to research Mason's illness and came upon the Hunter's Hope Foundation, an advocacy organization for universal neonatal screening.

“She sent me this pamphlet outlining the discrepancies in newborn screening from state to state,” Saul said. “I didn't know how to make meaning of it, but I thought the best way to honor her and Mason was to make other physicians aware of the discrepancies.”

A Cause Makes Its Way to the AMA

Saul brought the cause to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry—where she is a member of the academy's Assembly of Regional Organizations—in the form of a resolution for universal neonatal screening of the 29 “core” genetic illnesses (see

Recommended Screening Panel for Newborns) recommended by the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG). Passed unanimously, the resolution also called for the academy to bring the issue to the attention of the AMA.

Academy assembly members Louis Kraus, M.D., and David Fassler, M.D., then brought it to the AMA's Section Council on Psychiatry, of which they are also members. In June the section council brought to the AMA House of Delegates a resolution calling on the association to “advocate for mandatory, comprehensive, and uniform screening of newborns for major hereditable disorders.”

Debate on the resolution was largely favorable, and the House of Delegates voted to reaffirm a 2006 AMA report on the issue consistent with the resolution's purpose. “The outcome was a good discussion, which definitely helped increase awareness of the issues pertaining to newborn screening,” said Fassler.

Even in the short period since Mason's death, the number of states requiring or recommending the full 29-condition panel of ACMG genetics tests—or close to the full panel—has increased dramatically.

As it happens, X-linked ADL is not among the 29 conditions. It was only in 2006 that researchers at the Kennedy Krieger Institute published results of a preliminary test of a newborn screen for the disease. Pilot-testing of the screen is expected to be completed in two years.

Decisions about neonatal genetic screening raise difficult ethical questions wrought by the revolution in genetics: What is the availability of cost-effective treatment for a disorder diagnosed by testing? How does one weigh the relative merits of screening for a disease such as X-linked ADL for which there is no cure, but only expensive ameliorative therapies that may—or may not—lengthen survival? And how does one account for the possibility that better treatments or cures may become available in the future, though at the time of testing they may not exist?

At Mason's memorial last year, a hundred or more friends gathered in the park to celebrate the short life of the child who loved his sister Kayla and SpongeBob Squarepants. They sang the SpongeBob theme song (“Who lives in a pineapple under the sea”?) and released 250 helium balloons—scrawled with messages to Mason using Sharpie markers—into the sky.

“He was a very colorful little boy,” his mother told Psychiatric News. “He was very much in love with his sister. Even right up to the end, nobody else could get him to laugh the way Kayla could.”

Information about the Kennedy Krieger Institute is posted at<www.kennedykrieger.org/>. Information about the Hunter's Hope Foundation is posted at<www.huntershope.org>. The American College of Medical Genetics' Web site is<www.acmg.net>.▪