Patients receiving mental health care in the general medical sector are those most likely to stop their treatment prematurely, while patients treated by psychiatrists are least likely to do so, according to an analysis of data from a U.S. national survey.

Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., and colleagues analyzed data collected from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication and found that 22.4 percent of the 1,164 adult respondents who had received mental health treatment in the prior 12 months told the survey interviewers that they had quit treatment before the care provider wanted them to.

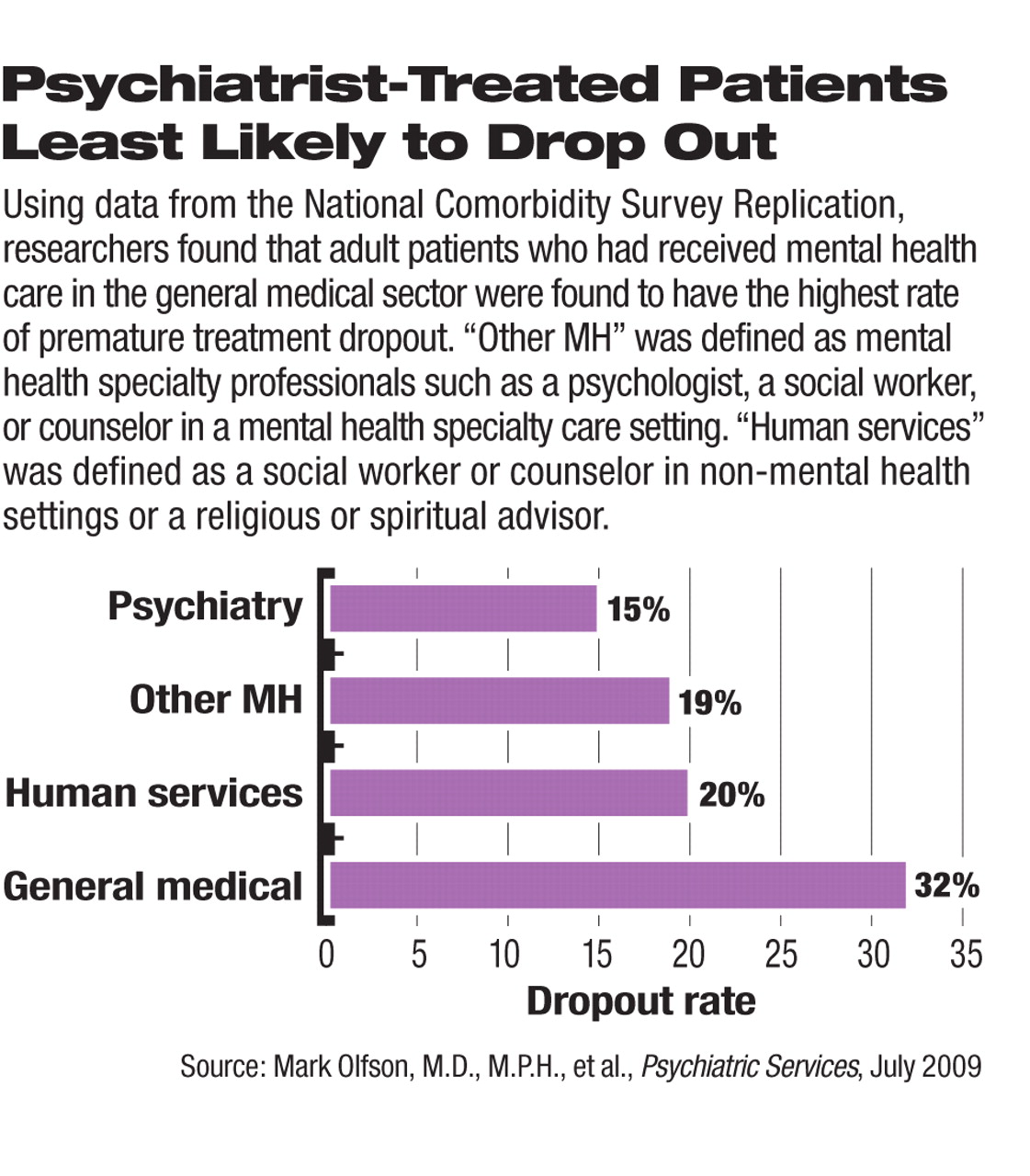

The dropout rates differed by the type of health care professionals. Patients receiving care in general medicine by primary care physicians, nurses, or other health professionals had a treatment dropout rate of 32 percent, while those seen by psychiatrists had a 15 percent rate (see chart).

The general medical sector was also the most frequently used source of mental health care, providing it for more than half (52 percent) of the respondents.

“The rates of treatment dropout vary widely across general medicine depending on the disease, patient population, and specific treatment,” Olfson told Psychiatric News. He pointed out that the 22.4 percent overall dropout rate in mental health treatment closely resembles the discontinuation rates for patients receiving some other medical treatments, such as adults prescribed beta-blockers following cardiac catheterization (also 22 percent). “Although the dropout rates from [treatment by] psychiatrists were lower than those from other health care professionals, premature discontinuation of psychiatric care remains unacceptably common,” he noted.

Olfson is a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons and the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Conducted from 2001 to 2003, the National Comorbidity Survey Replication collected mental disorder data from face-to-face interviews in a nationally representative community sample of adults throughout the United States. The study was published in the July Psychiatric Services.

The authors sifted through an abundance of survey data to uncover a number of factors that may help clinicians identify patients at a high risk of prematurely terminating treatment for mental illness. For example, race and ethnicity generally were not associated with treatment dropout, except that non-Hispanic black patients were significantly more likely than whites to drop out of treatment with psychiatrists than with general medical or nonpsychiatrist mental health professionals. In addition, younger patients—those aged 18 to 29—were more likely to drop out after the first two visits than were patients aged 60 or older, a trend that reached statistical significance only among those treated by psychiatrists.

Certain clinical and social characteristics also significantly predicted treatment dropout in all treatment settings. “Patients who lack health insurance and those who have not previously received mental health services were both at exceptionally high risk of dropping out of psychiatric care,” Olfson emphasized. “Economic realities as well as the patient's familiarity with mental health care are likely to weigh heavily on [his or her] decision to continue or prematurely terminate treatment.”

In the overall assessment across providers, patients with substance use disorders were more likely to drop out after the first two visits, but patients receiving collaborative care from several types of health professionals, such as a psychiatrist working with a general physician, were more likely to remain in treatment.

The authors also discovered that the first two visits were critical for convincing patients to stick with the treatment. More than 70 percent of all dropouts took place after one or two visits. Olfson urged clinicians to focus on engaging patients in the first few encounters. “Some patient groups, particularly younger adults, were at a high risk of dropout during the early stage of treatment,” he noted.

“Dropout From Outpatient Mental Health Care in the United States” is posted at<ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/60/7/898>.▪