How many compulsive, histrionic, paranoid, or other disordered personalities are you going to encounter on your next trip to France, Ireland, or some other Western European country?

Probably fewer—if any at all—than in the United States, a study published in the July British Journal of Psychiatry suggests.

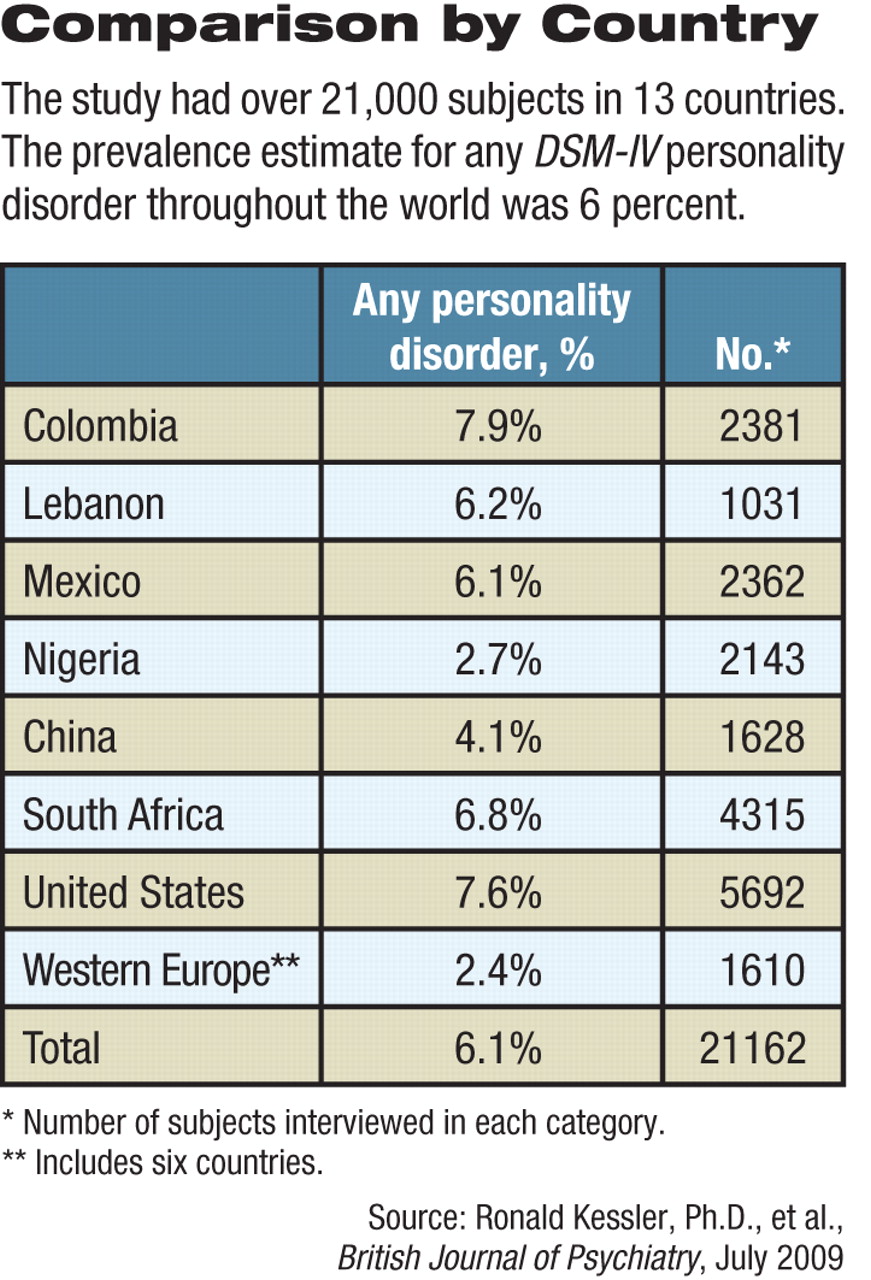

The interview-styled study of thousands of people the world over found the highest prevalence of personality disorders in Colombia and the United States and the lowest in Nigeria and Western Europe, with some other countries falling in-between.

Now, are there truly more disordered personalities in certain countries than others? Possibly, the study's lead investigator, Ronald Kessler, Ph.D., a professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School and head of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication in the United States, told Psychiatric News. The reason to believe that this might be the case is that “we have no data that can be used . . . for making a different assumption. But caution is needed in interpreting cross-national differences . . . because clinical reappraisal studies were not done in all countries to confirm comparability of diagnostic thresholds in the instrument.”

This study appears to be the first ever to estimate the prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in various countries throughout the world. If the study methodology was sound, here are other noteworthy findings:

• The prevalence estimate for any personality disorder throughout the world was 6.1 percent. The prevalence estimate of Cluster A personality disorders (paranoid, schizoid, and schizotypal) was 3.6 percent, while for Cluster B personality disorders (avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive) it was 2.7 percent, and for Cluster C personality disorders (antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic), 1.5 percent. Some subjects had more than one disorder.

• Cluster A personality disorders were much more common in men than women. The researchers wrote that this was their strongest finding and was consistent with a statement in DSM-IV.

• There was a high comorbidity between personality disorders and Axis I disorders, which jibes with a lot of clinical research findings. For example, cluster B personality disorders and substance abuse disorders often went hand in hand. The reason is probably because low impulse control is a core feature of both cluster B disorders and substance abuse disorders, the researchers wrote. Cluster C personality disorders and anxiety and mood disorders often coexisted. This finding is consistent with the belief that anxiety is a hallmark of cluster C disorders, the researchers noted.

• A dose-response relationship was found between personality disorders and the number of Axis I disorders people have. For instance, the odds of having three or more Axis I disorders were 10 times greater in individuals with cluster A personality disorders than in individuals without a personality disorder, 35 times greater in individuals with cluster C personality disorders than in individuals without a personality disorder, and a whopping 49 times greater in individuals with cluster B personality disorders than in individuals without a personality disorder.

The finding that he found the most important, Kessler said, concerned personality disorders and functional impairment. “So many times people raise the question of whether our findings about impairments associated with depression, alcoholism, PTSD, and so on are really due to some unmeasured character disorder that we could assess only if we had an Axis II assessment, which we seldom have in clinical or community studies. Our finding in this paper is that it's the other way around: Axis I disorders are the ones associated with most of the impairment, and the impairments associated with Axis II disorders are largely mediated by Axis I disorders.”

The study included over 21,000 subjects from 13 countries. Subjects from nine of the countries were nationally representative; those from the remaining four countries were representative of urban areas. All subjects were evaluated face to face by trained lay interviewers using the World Health Organization World Mental Health interview schedule.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the U.S. Public Health Service, the Fogarty International Center, the Pan American Health Organization, and some pharmaceutical companies.