The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the Department of Defense have stepped up efforts in recent years to develop and refine procedures for identifying, preventing, and treating mental health problems among veterans and active-duty personnel. That sense of urgency also lies behind the steady flow of epidemiological studies tracking mental health status and risk factors among these populations.

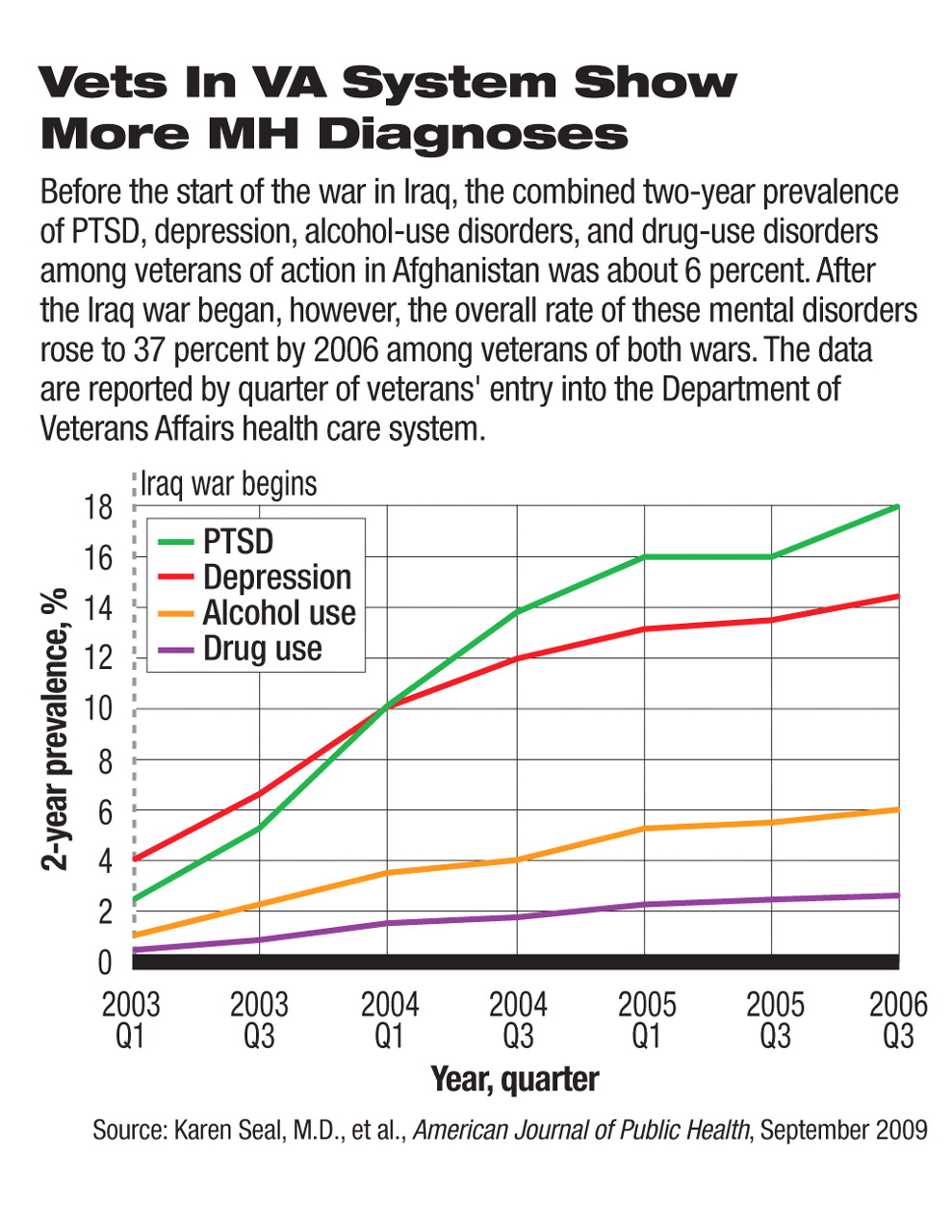

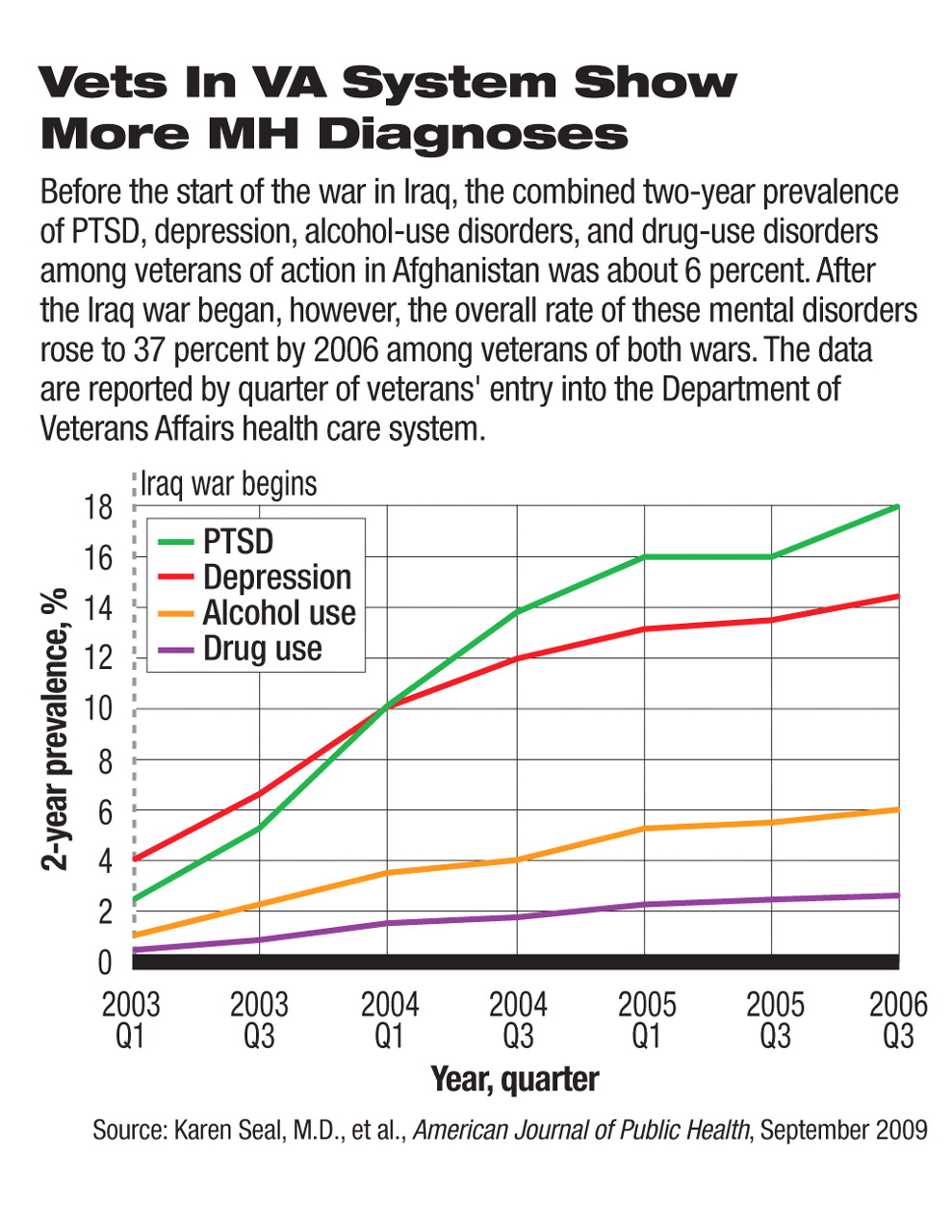

A report in the September American Journal of Public Health assessed data on 289,328 veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who had entered VA health care for the first time between April 2002 and March 31, 2008. Of those veterans, 106,726 (or 37 percent) received new mental health diagnoses. That compared with 28 in the first cohort of 439 veterans (6 percent) in April 2002, and thus represented a sixfold increase in six years. Adding psychosocial and behavioral problems (like marital and family problems) to the mix increased prevalence to almost 43 percent, according to Karen Seal, M.D., M.P.H., of the San Francisco VA Medical Center and the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues.

About 22 percent (62,929) of the veterans were newly diagnosed with PTSD, four to seven times the prevalence rate at the start of the Iraq invasion. The prevalence rates of depression and alcohol and drug abuse disorders rose as well.

The prevalence of new mental health diagnoses increased steadily as time passed. Of the veterans entering VA care at the beginning of 2004, 14.6 percent had received mental health diagnoses after one year, 20.3 percent after two years, and 27.5 percent after four years.

After adjustment for sociodemographic and military service characteristics stratified by component type, younger (aged 24 and under) active-duty troops had a greater risk for new mental health diagnoses (aside from depression) compared with veterans over age 40. They also had twice the risk for PTSD and alcohol-use disorders, and five times the risk for drug-use disorders. Some of that difference may be due to differential combat exposure, wrote the authors.

However, among National Guard and Reserve troops, the risk for depression and PTSD was higher among the older cohort.

Seal noted that these rates are higher than some previously reported among troops on active duty, perhaps reflecting “that veterans seeking VA care may have less stigma- and career-related concerns than do active military personnel about disclosing mental health problems, and VA clinicians may be more apt to record mental health diagnoses in the clinical record than are military health providers.”

An increased willingness to seek mental health care may be reflected in a study that found persons with current or past active-duty military experience recorded similar psychological distress scores on the 2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survey as those without such experience, but were more likely to have had recent mental health treatment, according to Marc Safran, M.D., M.P.A., senior psychiatrist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues, in the June International Journal of Public Health.

Whether this reflects a lessening of stigma regarding treatment should be explored in future research, wrote Safran and colleagues.

The number of suicides among active troops and veterans has reached the point where the Army recently commissioned a $50 million study through the National Institute of Mental Health to seek solutions to the problem (Psychiatric News, August 21).

In a July 2007 article in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, Mark Kaplan, Ph.D., a professor of community health at Oregon's Portland State University, and colleagues found that veterans were twice as likely to die of suicide compared with nonveterans in the general population. Kaplan used data on 320,890 men drawn from the U.S. National Health Interview Surveys.

Suicide is a rare and complex phenomenon, so no single cause will be found for its increased prevalence among veterans, said Kaplan in an interview. He suggested that a number of factors may contribute to their risk: desensitization to death and killing, a culture of stoicism and an allied difficulty in articulating feelings, a lack of preparation for life after the service, and a familiarity with firearms.

Kaplan pointed out that 8 out of 10 suicides among younger veterans in their study involved guns, and suicide attempts by firearms are usually impulsive and successful. Thus, the chance of rescue or survival is very slim.

More recently, other VA researchers reported on the relationship between PTSD and suicidal ideation in veterans presenting for mental health care at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System from 2004 to 2007.

They studied 435 veterans of the Iraq or Afghan war assessed and referred for mental health treatment, wrote psychologist Matthew Jakupcak, Ph.D., and colleagues in the August Journal of Traumatic Stress. Jakupcak is a researcher at the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System and an acting assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

To evaluate these veterans, they used the military version of the PTSD Checklist, the Patient Health Questionnaire depression subscale, and the Addiction Severity Index. Patients were recorded as having suicidal ideation if they endorsed at least one of five items drawn from the Mississippi Scale for PTSD and the Scale for Suicidal Ideation.

Data were available for 407 veterans, 187 with suicidal ideation and 220 without. After controlling for age, depression, and substance abuse, veterans with PTSD were four times more likely to acknowledge suicidal ideation than those without.

The researchers also analyzed data from the veterans who screened positive for PTSD (n=202) to examine the effects of psychiatric comorbidities. Veterans with PTSD and one comorbidity (depression or substance abuse) were no more likely to exhibit suicidal ideation than those with only PTSD. However, those with at least two comorbidities were 5.7 times more likely to exhibit suicidal ideation.

“Current findings underscore the importance of assessing for suicidal ideation in [Iraq and Afghan] veterans, especially among PTSD veterans with complex psychiatric profiles,” the researchers wrote.

“This confirms prior research showing that veterans with mental health problems are at higher risk for suicidality,” said Jakupcak in an interview. These problems cannot be viewed in isolation, he said. “Many veterans are presenting with complex physical injuries, pain, traumatic brain injuries, and psychiatric symptoms.”

Finally, a small, qualitative study of 16 returning veterans of the current conflicts concluded that the strategies needed to cope with combat made reintegration into life back home more difficult. That conflict led veterans to feel burdensome to people around them and into failed relationships with civilians, said Lisa Brenner, Ph.D., of the VA's Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center in Denver and an assistant clinical professor of psychology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

“Working with veterans to decrease their suicide risk is likely to require multiple interventions and creative adaptations of existing approaches,” wrote Brenner in the July 2008 Journal of Mental Health Counseling.

An abstract of “Trends and Risk Factors for Mental Health Diagnoses Among Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans Using Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care, 2002–2008” is posted at<www.ajph.org/cgi/content/abstract/99/9/1651>. An abstract of “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder as a Risk Factor for Suicidal Ideation in Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans” is posted at<www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/122519727/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0>.▪